2019 MP3 Recording of Original VOA Audio, Video with NASA Photographs, Transcript and Images of VOA’s 1969 LP Record by Cold War Radio Museum

2019 MP3 Recording of Original VOA Audio, Video with NASA Photographs, Transcript and Images of VOA’s 1969 LP Record by Cold War Radio Museum

In 1948, Democrats and Republicans in the U.S. Senate charged that Voice of America (VOA) broadcasts contained “baloney,” “lies,” “insults,” “drivel,” “nonsense and falsehoods,” amounting to “useless expenditures” and “a downright tragedy.”

In 1948, U.S. senators called VOA programs “ridiculous,” “unjustified” and “deplorable.” Liberal, moderate, and conservative lawmakers, some of whom even accused the Voice of America of “slander” and “libel” in how several U.S. states were described in radio programs acquired from NBC under a government contract, did not seek to de-fund and close down VOA but wanted to make it more effective in presenting America to the world and in countering propaganda from Soviet Russia. Their criticism eventually led to partial personnel and programming reforms in the early 1950s. In 2019, history seems to be repeating itself, with similar problems being reported at the Voice of America as the United States tries to respond to propaganda from Putin’s Russia, communist China, theocratic Iran and other nations under authoritarian rule. Today, there is little interest in the U.S. Congress and no obvious signs of management reforms, while some of the problems seem now more difficult to solve than those besetting the broadcaster in 1948.

During the Cold War, Voice of America (VOA) broadcast mostly radio programs. Most of the radio transmissions were delivered through shortwave. VOA would send out QSL cards as a written confirmation of reception to those listeners who requested them by letter. The 1978 QSL card from VOA was a post card with pictures of San Francisco, the White House and the Statue of…

Rep. Howard H. Buffett, father of American investor Warren Buffett, was concerned in 1947 about domestic propaganda activities by the Voice of America.

As the U.S. Congress was debating in June 1947 the eventual passage of the Smith-Mundt Act, which implicitly placed restrictions on domestic dissemination of government news through the Voice of America (VOA) while funding expansion of State Department’s cultural and academic exchange programs, Congressman Howard Buffett (R-NE) expressed concerns that officials in charge of VOA may have been secretly planning domestic propaganda activities. As it turned out, State Department officials had no plans to distribute U.S. government radio broadcasts domestically because such a move would kill the funding not only for VOA but also for the public diplomacy programs the State Department cared about most of all. Congressman Buffett was right, however, that U.S. diplomats were using VOA to influence U.S. public opinion to drum up support for their information outreach budget.

By Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

Two extraordinary refugees from Poland helped to expose in 1956 to the U.S. Congress anti-U.S. propaganda activities of a communist journalist Stefan Arski, also known as Artur Salman.

The News Bureau room of the Office of War Information (OWI), November 1942, at about the same time Howard Fast started writing Voice of America newscasts. The photograph’s official caption said: “It is arranged much the same way as the city room of a daily newspaper. Here, war news of the world is disseminated. In the foreground, are editors’ desks handling such special services as trade press, women’s activities, and campaigns. The news desk is in the background.” Smith, Roger, photographer. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540.

“I established contact at the Soviet embassy with people who spoke English and were willing to feed me important bits and pieces from their side of the wire. I had long ago, somewhat facetiously, suggested ‘Yankee Doodle’ as our musical signal, and now that silly little jingle was a power cue, a note of hope everywhere on earth…” 1

Howard Fast, 1953 Stalin Peace Prize winner, best-selling author, journalist, former Communist Party member and reporter for its newspaper The Daily Worker, decribing his role as the chief writer of Voice of America (VOA) radio news translated into multiple languages and rebroadcast for four hours daily to Europe through medium wave transmitters leased from the BBC in 1942-1943. Howard Fast, Being Red (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), pp. 18-19.

By Ted Lipien

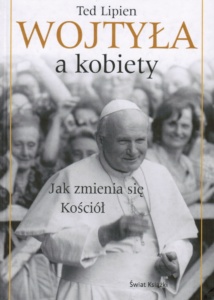

In my book, Wojtyła’s Women: How They Shaped the life of Pope John Paul II and Changed the Catholic Church, I describe how future Pope John Paul II, whom I had interviewed in Washington D.C. for the Voice of America (VOA) in 1976 when he was Kraków’s Archbishop, became familiar with many stories of immense suffering of Polish women under both Nazi and Soviet occupation. 1

Notes:

Throughout World War II, the arrests and forced deportations of Polish families to labor camps by Soviet Russia received practically no mainstream media coverage in the United States. After the Soviet Union became an important military ally against Nazi Germany with the sudden collapse of Stalin’s alliance with Hitler and his attack on Russia in June 1941, the propaganda agency of the Roosevelt administration–the Office of War Information (OWI)–deliberately covered up Stalin’s crimes, both the deportations of millions of people to Siberia and the mass executions of Polish prisoners of war.

A statement made on the floor of the U.S. Senate on February 8, 1940 by Senator John A. Danaher (R-Connecticut) may have been the first major public reference in the United States to the 1940 deportations of Poles and other nationalities to Gulag forced labor camps in the Soviet Union. Senator Danaher inserted in the Congressional Record the text of a resolution adopted by of the Star of Liberty Society, Group 803, of the Polish National Alliance in Stamford, Conn. It mentions in one sentence “the deportation of large numbers of Poles to Siberia.” The Polish-American organization in Connecticut adopted the resolution on January 14, 1940. By then the news of the first deportations of Poles from Soviet-occupied eastern Poland to Siberia and other parts of the Soviet Union had already reached some Polish-Americans but was not known to most Americans.

Following the August 1939 Hitler-Stalin Pact and the joint German-Soviet invasion of Poland in September 1939, which started World War II, the Soviets began the first mass deportation of Poles on February 10, 1940 from the occupied eastern part of Poland. Whole families were arrested, usually early in the morning, and sent in overcrowded cattle train wagons to forced labor camps in the depths of Siberia and in other parts of the Soviet Union. Many elderly and infants died during the transport–bodies of some of the children tossed by guards into the snow; others left behind at various stops during the journey lasting many days with little food or water. Many more prisoners would die later in the Gulag camps, work settlements and collective farms from slave labor, harsh weather conditions, starvation, and lack of medial treatment.

There was almost a complete media silence in the West about the deportations. Western journalists either did not know or were afraid or unwilling to report on what was happening to millions of Stalin’s prisoners. In addition to Polish citizens, the Soviets also imprisoned and deported Russians, Ukrainians, Belorussians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, Tatars, Jews and members of many other ethnic and religious groups. Even after the war, the story of the deportees was rarely told. Many of those who had survived the Gulag camps, became refugees in the West unable to return to their homes.