By Ted Lipien

“The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.”

― L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between

In the early 1980s, vehemently anti-Reagan Voice of America (VOA) central English newsroom journalists, almost all of them U.S.-born, engaged in dogged resistance against officials and managers selected by the new administration to run the U.S. taxpayer-funded international media outlet operating within the federal government. These VOA government workers and their supporters within the agency’s bureaucratic management ultimately lost their fight against the new Republican president’s tough policy of criticizing the Soviet Union and other communist-ruled nations, but they still managed to generate considerable U.S. media publicity for themselves and forced one outspoken but minor Reagan administration appointee out of his government job. What they failed to do is to stop program changes at the Voice of America planned by the Reagan administration–management reforms which I and others would credit with helping to speed up the collapse of the Soviet Union in about ten years later.

The efforts of these well-paid federal government managers and privileged employees working as VOA English newsroom journalists were ultimately unsuccessful because, in my view, they themselves were completely insignificant within the U.S. government foreign policy establishment. More importantly, they lacked any kind of broad public support in the United States, especially from leaders and members of ethnic and immigrant communities who were strongly anti-communist. In their partisan zeal to oppose Ronald Reagan, they also managed to antagonize their less compensated and severely discriminated against foreign-born colleagues in VOA’s major language services who actually performed almost all of the agency’s important work.

I should note that VOA newsroom editors and reporters who fought with Reagan appointees were not at all pro-Soviet as opposed to some of the early VOA journalists who actually had spread Soviet propaganda and helped Stalin install pro-Kremlin regimes in East-Central Europe–a shameful period in VOA’s history which has been largely hidden and forgotten. 1 There were also in the early 1980s a few VOA central newsroom employees who had a East European family background, in some cases European university education, and a good understanding of international politics and who did not agree at all with the anti-Reagan campaign of some of their newsroom colleagues. But the majority in the VOA newsroom believed in the need to continue the policy of détente with the Soviet Union and with the Soviet block which was supported by the Washington foreign policy establishment and by various U.S. administrations representing both political parties. Ronald Reagan’s rhetoric challenged their familiar worldview and their preferred vision of U.S. government-funded international broadcasting. For partisan and ideological reasons, Ronald Reagan and his appointees at the Voice of America were unacceptable to this group of American journalists.

Reagan-appointed officials, who had a plan of enhancing and changing U.S. broadcasts to the Soviet block, ignored protests from the VOA newsroom and instead gave refugee journalists at the Voice of America freedom to expose the failures of communism. This was a major change from what these “emigrés” could do as broadcasters in prior years under their previous VOA and United States Information Agency (USIA) managers. This changed as soon as some of the longtime managers were reassigned to less important positions by the new Reagan team. At that time, foreign-born journalists working for VOA were often described by some of their newsroom colleagues and in U.S. media as “emigrés,” a term which already then had a pejorative meaning. I prefer to refer to call them refugee journalists since many of them were in fact political refugees who would have been immediately arrested or otherwise persecuted if they returned to their home countries then under communist rule unless of course they would be willing to condemn their employers and the United States. [The current name for VOA’s parent federal agency is the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM).]

Former VOA program director and journalist Alan Heil, who was one of the longtime managers reassigned by the Reagan team at the beginning of the 1980s, wrote about the period of change after the new administration took office as “the dark days of 1981 and 1982.” 2 New York Times reporter Barbara Crossette wrote in a March 28, 1982 article titled, “There is a Voice of America; but its tone is in dispute,” that “The turmoil has cost the Voice a respected news director and several other professionals who felt a decade of struggling to gain credibility was being eroded by a shift away from hard news and into policy broadcasting.” 3 Many of VOA’s foreign language broadcasters, however, felt liberated by these changes and their new freedom to report on topics which were previously off limits or severely restricted. While former managers and VOA newsroom dissidents made then and later various, mostly vastly exaggerated or misleading complaints of journalistic malpractice and censorship, no major programming scandals in broadcasting to the Soviet block by VOA foreign language services occurred during the Reagan years, as far as I could discover. In contrast, there were numerous embarrassing U.S. media reports on censorship at the Voice of America and rebukes from Congress and listeners behind the iron curtain during various previous periods in VOA’s history. 4

There was in fact a major editorial freedom problem at the Voice of America at the time before Ronald Reagan won U.S. presidency in 1980, but ironically it occurred without much notice by outside media and was created by pre-Reagan managers and journalists who were then lashing against Reagan appointees and policy changes. The internal censorship problem, which was exactly the opposite of what VOA central English newsroom journalists were warning against and totally different than what most U.S. media were reporting, was then successfully solved by new officials appointed by Reagan to run VOA. The dramatic improvement occurred again without much reporting by U.S. media because it would have shown that their earlier news accounts about censorship and propaganda allegedly promoted at VOA by Reagan appointees were largely inaccurate and that most of the personnel changes and management reforms were necessary.

In a somewhat more balanced account of the Voice of America 1980s troubles, conservative journalist Tom Bethell wrote in the May 1982 issue of generally liberal Harper’s magazine that before Ronald Reagan was elected to U.S. presidency in 1980, “some of the ’emigrés’ in [VOA’s] foreign language [USSR] division were amazed to find that they were having difficulty getting Alexandr Solzhenitsyn on the air.” 5 Bethell reported that Russian Service journalist Ludmilla Foster, who came to the U.S. from the Soviet Union in 1950, was told by a foreign service officer at VOA that excerpts from Solzhenitsyn’s new book could not be repeated.

After President Reagan appointed his personal friend Charles Z. Wick as head of U.S. International Communication Agency (USICA) [USIA was temporarily renamed USICA during the Carter administration] such censorship quickly ended, but even under Wick it was initially strongly defended by some USIA and VOA officials. Tom Bethell reported that according to them, Solzhenitsyn engaged “in an objectionable form of Russian nationalism, and that he is very unpopular except with a small group of intellectuals.” 6 Without realizing it, they were repeating Soviet KGB propaganda. 7

Reagan’s critics in the VOA newsroom said that his assessment of the Soviet Union and the vision of his officials of how VOA should do news would result in crude propaganda, would lower America’s standing in the world and would increase international tensions. These VOA newsroom journalists had many friendly media contacts in the United States who shared their anti-Reagan sentiments. As Tom Bethell reported in Harper’s, as a result of their “Editorials and features complained that VOA was being ‘politicized,’ ‘McCarthyism’ was in the air, the agency’s credibility was being threatened, and propaganda was the new order of the day.” He described it as “a harmonious hum from the press across the country” elicited from “within VOA,” or more precisely from among Reagan’s critics at VOA. 8

Bethell also pointed out, quite correctly in my view, that the Soviets were not at all displeased by the charges of new “McCarthyism” from VOA newsroom reporters being amplified by U.S. media “because it would presumably undermine VOA credibility.” 9 In my view, VOA listeners, especially in Eastern Europe, could not care less what a small group of VOA central English newsroom Americans and Soviet journalists were saying about the Voice of America, but their activities had some impact on U.S. public opinion.

Most accusations made by VOA newsroom dissidents in the 1980s to outside media were hysterical and groundless and in some ways much more similar in tone to Soviet propaganda than anything produced by VOA foreign-born journalists. If anything, Reagan-appointed managers brought with them much needed new journalistic freedom to the Voice of America. Nothing that VOA foreign language services reported on their own during Reagan years, as far as I had observed at the time or could discover later, was false, deceptive or enticing violence. It was simply more honest and more effective than what the VOA central English newsroom was doing in prior years while denying foreign language editors and reporters direct access to wire services and ability to generate their own reporting without burdensome restrictions.

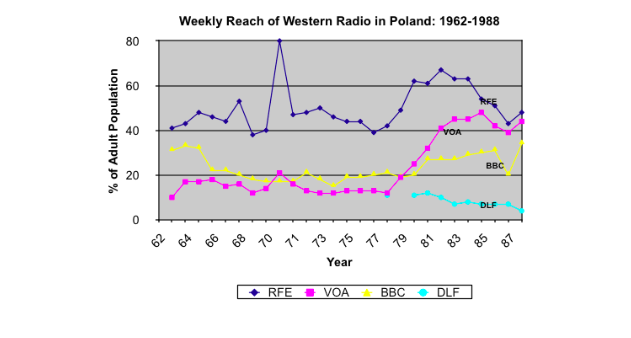

VOA’s audiences behind the iron and bamboo curtains definitely welcomed Reagan’s tougher stand against communism. By the end of the 1980s, the results of the new information policy toward the Kremlin, his administration‘s management reforms at the Voice of America and the increase of funding were nothing short of impressive. VOA’s audience in Poland grew fivefold under Reagan-appointed higher-level managers who took over key agency and VOA positions. Most lower-level managers were not changed.

Listenership to VOA programs also increased during the Reagan years in Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and Romania but not as dramatically as in Poland which led the peaceful opposition to communism in East-Central Europe. By the end of the 1980s communism in Eastern Europe was on its way out and the Soviet Union would soon collapse.

How much Radio Free Europe and the Voice of America had contributed to the fall of communism in Eastern Europe and in the Soviet Union cannot be easily determined, but most scholars agree that RFE, Radio Liberty (RL) which broadcast to the Soviet Union, and the Voice of America made a major contribution in addition to any credit that must go to East European opposition activists, the independent Solidarity trade union in Poland led by Lech Wałęsa, Soviet dissidents, Polish-born Pope John Paul II, Ronald Reagan, and to some degree the last Soviet communist leader Mikhail Gorbachev and his policies of glasnost and perestroika.

R. Eugene Parta, “Listening Rates to Western Radio Stations in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Bulgaria: 1962-1988,” Conference on Cold War Broadcasting Impact, Stanford, California, October 13-15, 2004.

Reagan administration’s information policies were successful because Ronald Reagan did not mince words about communism and the Soviet Union, which he called “the evil empire.” He increased funding for VOA foreign language services broadcasting to communist ruled-nations and managers appointed by his administration removed restrictions on criticizing communist regimes. VOA’s Polish Service benefitted greatly from these changes. The success of the Reagan years at the Voice of America was also partly due to foreign-born journalists who stood up to their VOA newsroom colleagues and agreed with Reagan’s tough approach to Soviet Russia because they knew Russia and communism far better than anyone in the VOA central newsroom. Before Reagan, the Polish Service and other foreign language services at VOA could barely afford to pay a few dollars to a very small number of stringers, most of them based in the United States, and were reduced to translating centrally-produced English-language reports, while VOA central English newsroom reporters were sent to live and work abroad under a special Foreign Service Officer status with almost all the perks and benefits given to State Department and USIA diplomats at a significant cost to American taxpayers.

Some of the news reports sent by VOA central newsroom correspondents from their overseas bureaus were useful, but many were inferior and less detailed compared to regular wire services reports to which foreign language services were denied direct access by the management. VOA newsroom correspondents could not match the knowledge and experience of some of their colleagues in foreign language services assigned to a second-class status. They desperately wanted to use their reporting skills but were prevented by the pre-Reagan management team from using them effectively. Before Reagan, VOA and USIA management denied them sufficient resources while the VOA newsroom managers denied them direct access to news and other information.

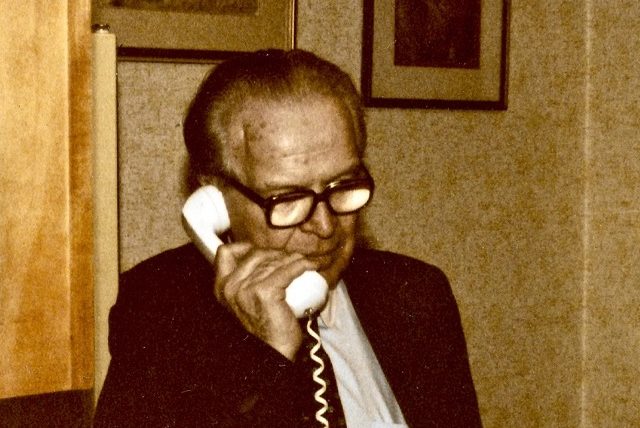

Unlike their colleagues in foreign language services, some of the VOA central newsroom reporters also had a somewhat naive view the Soviet Union and communism which contributed to VOA’s low audience reach and lower impact in Eastern Europe before the 1980s compared to the reach and impact of Radio Free Europe broadcasts. Fortunately, when some of the programming restrictions were lifted during the Reagan administration, among refugee VOA journalists in the 1980s in foreign language services there were still some who had been prisoners in the Soviet Gulag or fought against the Nazis during World War II, were excellent reporters and writers, and knew how to counter propaganda without resorting to propaganda. One of them was the VOA Polish Service stinger in New York Zdzisław Bau who also worked for Radio Free Europe and reported in Spanish for newspapers in Argentina. In 1983, Bau was interviewing Solidarity activists arriving to the U.S. after being released from detention in Poland and receiving political asylum. Refugee journalists like Bau, who had already discovered the true nature of communism by talking to travelers coming from the Soviet Union to Poland in the 1930s, survived Soviet labor camps and was a war correspondent with the Polish forces fighting the Nazis in Western Europe toward the end of the war, could not be fooled by Soviet propaganda, disinformation and peace offensives.

Refugees coming to New York from Poland in the early 1980s said that Solidarity leaders admired Ronald Reagan and were listening to his speeches on radios smuggled into internment camps for political prisoners. Solidarity activist Mirosław Domińczyk, who was imprisoned by the military regime of General Wojciech Jaruzelski after the communist leader declared martial law on December 13, 1981, told Zdzisław Bau in an interview conducted in New York in 1983 that in their internment camps Solidarity prisoners sang a song about President Reagan.

Bau’s radio name in Voice of America programs was Andrzej Holik.

ANDRZEJ HOLIK (ZDZISŁAW BAU), VOA POLISH SERVICE: Did you know what was happening in the world? Did you have any outside contacts?

MIROSLAW DOMIŃCZYK, SOLIDARITY ACTIVIST: Only later, after about a month. When the first visits started, we received radios. I mean, they were smuggled in ingenious ways, hidden in lard, in other products. We then listened regularly to the Voice of America, Radio Free Europe. We could receive all stations, but Radio Free Europe was difficult to hear [because of strong jamming of the radio signal]. Therefore, our source of information was the Voice of America and our families who were visiting.

ANDRZEJ HOLIK (ZDZISŁAW BAU), VOA POLISH SERVICE: What was the mood in the internment camp?

MIROSLAW DOMIŃCZYK, SOLIDARITY ACTIVIST: It depends during which period, but mostly it was cheerful, we sang songs. They were about Reagan.

ANDRZEJ HOLIK (ZDZISŁAW BAU), VOA POLISH SERVICE: What was the song about President Reagan?

MIROSLAW DOMIŃCZYK, SOLIDARITY ACTIVIST: To the melody of Glory, Glory, Hallelujah, “Reagan is our greatest friend.” I’m not a singer, otherwise I would sing it, but there are recordings. May be later I’ll present them.

ANDRZEJ HOLIK (ZDZISŁAW BAU) VOA POLISH SERVICE: He was so popular among you?

MIROSLAW DOMIŃCZYK, SOLIDARITY ACTIVIST: He was and still is, yes.

Interview with Solidarity activist Mirosław Domińczyk recorded in New York in early 1983 by VOA Polish Service stringer Zdzisław Bau (VOA radio name Andrzej Holik).

The view of Ronald Reagan and his foreign policy was also overwhelmingly positive in the VOA foreign language services broadcasting to nations under communist rule. He was only deeply disliked and even despised by VOA newsroom editors and reporters who had never experienced life under communism and were motivated largely by domestic U.S. politics and partisan passions which they were unable to control despite the obligations of the VOA Charter, which was the 1976 U.S. law mandating that the Voice of America “will represent America, not any single segment of American society, and will therefore present a balanced and comprehensive projection of significant American thought and institutions,” and that “VOA news will be accurate, objective, and comprehensive.”

When about a hundred VOA central English newsroom editors and reporters signed a petition expressing “outrage” at new programming proposals and demanding that one of Reagan administration’s appointees be fired, Tom Bethell reported in Harper’s magazine in May 1982 that in response about 200 of the “emigrés” signed a counterpetition. The risk to refugee journalists of signing any public petitions was much greater than to U.S.-born VOA newsroom reporters, yet more of them decided to express their support for programming and management reforms at the Voice of America and criticized their newsroom colleagues.

“We are shocked,” part of the emigré petition read “that VOA’s media informers are ‘distressed’ that VOA should want to ‘draw a rosy picture of the United States.’ As federal employees, we owe it to the taxpayers who provide out salaries to put American life in perspective. If in the course of doing so the U.S. image turns out to be positive–what’s wrong with that?” 10

Tom Bethell, “Propaganda Warts: What the Voice of America makes of America,” Harper’s, May 1982, p. 24.

Former VOA deputy director and journalist Alan L. Heil, Jr. offers a different view and narrative in his book, Voice of America: A History, published by Columbia University Press in 2003. He does not specifically mention the competing petition signed by a much larger number of VOA foreign language journalists who defended Reagan’s management reforms. Heil, who in his book refers to personnel changes at the agency as “The Purges,” claims that these VOA refugee broadcasters supporting the new management were “a vocal minority.” My own assessment was that it was a clear majority and far less vocal and more intimidated by years of discrimination than their native-born colleagues in the VOA central English newsroom. Here is Alan Heil’s description of pro-Reagan VOA

refugee journalists:

A vocal minority in the language services, mostly East European in origin, agreed with the Reagan appointees that VOA programming should be more strident against the Soviet Union. They believed that central news still placed too much emphasis on events in the United States that they regarded as of little interest to their audiences. The language broadcasters also assailed what they regarded as an unfair system. They complained about being “reduced to translating. It’s a feudal system,” explained one. He contended that at VOA in 1982, bilingualism for any employee was a liability, adding: “The accent dooms us to serfdom.”[Charles Fenyvesi, “I Hear America Mumbling,” Washington Post Magazine, July 19, 1981.] A few of the language service activists saw an opportunity to enhance their influence or even gain appointments to senior Voice positions. 11

Alain L. Heil, Jr., Voice of America: A History (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 200.

Tom Bethell offered in his Harper’s article a quite different and, in my own assessment as someone who had observed these events first-hand, quite accurate portrayal of VOA foreign language journalists and VOA central English newsroom editors and reporters.

Unlike the emigrés, who were usually afraid to speak for attribution, and even tended to fear their phones might be tapped, newsroom people were blithely outspoken in their criticism of the new administration. 12

Tom Bethell, “Propaganda Warts: What the Voice of America makes of America,” Harper’s, May 1982, page 25.

I was in charge of VOA broadcasts to Poland in the 1980s, working both as a service manager and a reporter. It was the most satisfying period in my entire journalistic career and during three decades of my U.S. government service at the Voice of America, the United States Information Agency and later at the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG). My last U.S. government position at VOA before I retired in 2006 was acting associate director in charge central programming, which included VOA English newsroom.

In subsequent research of VOA history, I discovered more evidence of ideological bias, foreign influence and mismanagement. I wrote articles about the secret removal by the Roosevelt administration of VOA’s first director John Houseman for hiring communist broadcasters, VOA’s first chief news editor and writer Howard Fast, a Communist Party member who in 1953 received the Stalin Peace Prize, criticism of VOA journalists by President Dwight Eisenhower, and about several VOA foreign language broadcasters who after their employment by VOA during World War II and in some cases immediately after the war went back to Eastern Europe to serve as anti-American propagandists and diplomats for communist regimes. Their journalism and their propaganda supported dictatorships which murdered hundreds of thousands of innocent people. One of them, Stefan Arski, aka Artur Salman, was in contact with Marxist economist Oskar R. Lange who was one of Stalin’s most important KGB-supervised agents of influence in the United States tasked by Moscow with getting President Roosevelt to agree to Soviet control over Poland after World War II. Arski used Lange as a reference in his application for his U.S. government job. In 1947, he went back to Poland to become a chief propagandist for the communist regime while Lange returned somewhat earlier to the United States as the regime’s ambassador to Washington. In the 1950s, the Voice of America bureau in Munich, West Germany, employed briefly a Polish communist spy. 13 This part of VOA’s history has been largely hidden from Americans by most journalists and by former VOA officials who may know about it but for various reasons prefer to remain silent.

Any of VOA’s historical failures are, however, far outweighed by its successes which occurred when reforms were carried out. In my view, Voice of America’s honor and credibility were saved thanks largely to outstanding refugee journalists like Zofia Korbońska, Zdzisław Bau, Ryszard Mossin, Zdzisław Dziekoński, Wacław Bniński Tomasz Dobrowolski, Irena Radwańska Broni, Marek Święcicki, Feliks Broniecki, Jan Grużewski and Marek Walicki. They were working in the VOA Polish Service. Journalists working in other foreign language services during the Cold War had similar backgrounds. They replaced pro-Soviet socialists and communists who were in charge of VOA broadcasts to Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and to other countries during World War II and in some cases for a few years after the war.

Former anti-Nazi underground resistance members like Zofia Korbońska and former Soviet Gulag prisoners like Zdzisław Bau had a direct knowledge of Fascism and Communism. While they were initially stifled by restrictions imposed by the management and by the VOA newsroom prior to the Reagan years, they eventually prevailed and achieved their goal of seeing democracy and free press restored in their native countries. And even when they could not broadcast everything they wanted, the Voice of America Polish Service, supplemented since 1950 by considerably more independent and more influential Radio Free Europe, still provided after about 1947 much needed encouraging news from the United States.

During Ronald Reagan’s presidency in the 1980s, the Polish Service of the Voice of America reported on the visits to the United States and to Poland by Pope John Paul II, managed to interview by phone and in person Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa and documented the fall of communism in Eastern Europe and the fall of the Soviet Union. We interviewed American experts, including former President Carter’s National Security Advisor Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski, but we also reported on criticism of President Reagan by Democrats and large segments of U.S. media. With the exception of a few VOA correspondents in Europe reporting in English and a few friendly central editors and reporters in the U.S., we did not have much use for those of our colleagues in the VOA English newsroom whose partisan hatred of Reagan and their lack of broader perspective, knowledge and journalistic curiosity put them on the wrong side of history.

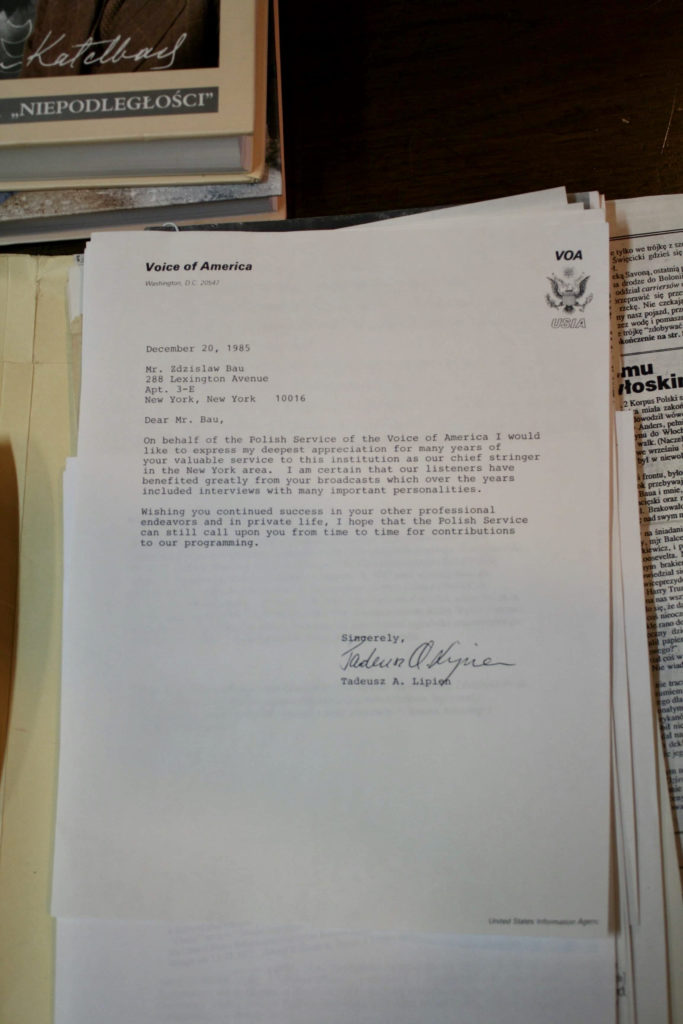

When in 1985 our chief stringer in New York Zdzisław Bau, who in his long journalistic career reported in many languages on former President Hoover’s visit to pre-World War II Poland, the Nazi-German and Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, other World War II battles and many of the main events of the Cold War, was scaling down on his work for the Voice of America, I sent him a thank-you letter.

Dear Mr. Bau,

On behalf of the Polish Service of the Voice of America I would like to express my deepest appreciation for many years of your valuable service to this institution as our chief stringer in the New York area. I am certain that our listeners have benefited greatly from your broadcasts which over the years included interviews with many important personalities.

Wishing you continued success in your other professional endeavors and in private life, I hope that the Polish Service can still call upon you from time to time for contributions to our programming.

Sincerely,

Tadeusz A. Lipien

Letter from Tadeusz (Ted) A. Lipien, VOA Polish Service chief to the service’s chief stringer in New York Zdzisław Bau (VOA radio name Andrzej Holik), dated December 20, 1985. (Courtesy of Bau family archive and Radosław Święs)

My short letter to Zdzisław Bau could not possibly fully reflect and give proper tribute to his great journalistic talent and his contribution to the fall of communism in Poland and elsewhere. During all the years I had worked for the Voice of America, Zdzisław Bau never told me that he was a prisoner in the Soviet Gulag. Born in Kraków in 1912, educated in Switzerland, a multilingual pre-war newspaper reporter in Poland, a slave laborer in the Soviet Union, a war correspondent, an editor and reporter for Argentinian media, a U.S. Information Service (USIS) editor at the U.S. Embassy in Buenos Aires, an editor and reporter for Polish American media, a stringer in New York for VOA and RFE–Zdzisław Bau died in New York on February 2, 1991. Polish journalist and media scholar Radosław Święs who lectures at the Opole University in Poland is currently working on a dissertation about Zdzisław Bau’s journalistic career.

Top photo: President Reagan meeting with Pope John Paul II at the Fairbanks Airport in Alaska, May 2, 1984. From Reagan Library Archives.

Notes:

- Ted Lipien, “Mira Złotowska – Michałowska — Soviet influence at WWII Voice of America,” Cold War Radio Museum, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/communist-mata-hari-at-wwii-voice-of-america/. ↩

- Alan Heil, Jr. Voice of America: A History.(New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 219. ↩

- Barbara Crossette, “There is a Voice of America; but its tone is in dispute,” New York Times, Section 4, Page 5, March 28, 1982. ↩

- Cold War Radio Museum, “Voice of America 1951 – ‘Drab’ ‘Unconvincing’,” February 24, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/2018/02/23/voice-of-america-1951-drab-and-unconvincing-rep.-wiggleswoth-quotes-listeners-in-poland/. ↩

- Tom Bethell, “Propaganda Warts: What the Voice of America makes of America,” Harper’s, May 1982, page 21. ↩

- Tom Bethell, “Propaganda Warts: What the Voice of America makes of America,” Harper’s, May 1982, page 21. ↩

- Ted Lipien, SOLZHENITSYN Target of KGB Propaganda and Censorship by Voice of America: How Voice of America Censored Solzhenitsyn, Cold War Radio Museum, November 7, 2017, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/solzhenitsyn-target-of-kgb-propaganda-and-censorship-by-voice-of-america/. ↩

- Tom Bethell, “Propaganda Warts: What the Voice of America makes of America,” Harper’s, May 1982, page 25. ↩

- Tom Bethell, Propaganda Warts: What the Voice of America makes of America, Harper’s, May 1982, page 24. ↩

- Tom Bethell, “Propaganda Warts: What the Voice of America makes of America,” Harper’s, May 1982, page 24. ↩

- Alain L. Heil, Jr., Voice of America: A History (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 200. ↩

- Tom Bethell, “Propaganda Warts: What the Voice of America makes of America,” Harper’s, May 1982, page 25. ↩

- Ted Lipien, “Dangerously naive VOA journalists make fools of themselves,” Washington Examiner, October 8, 2020, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/op-eds/dangerously-naive-voa-journalists-make-fools-of-themselves. ↩