By Ted Lipien

One of the most principled and courageous Voice of America (VOA) journalists, Konstanty Broel Plater, was born in Poland 111 years ago on September 19, 1909, yet his name remains unknown to nearly all VOA employees who have been convinced by successive U.S. government broadcasting leaders that the first VOA director John Houseman who in reality invented fake radio news and hired pro-Soviet communists to produce VOA programs during World War II was responsible for making the organization forever committed to telling the truth. Konstanty Broel Plater resigned in April 1944 as a Voice of America Polish service radio announcer in protest against broadcasting Soviet propaganda lies on orders from VOA directors.

Melior Mors Macula (Better Death Than Blemish)

Broel Plater family motto

The only known Voice of America (VOA) employee who had refused to read Stalin’s lies and resigned in 1944 in protest against Soviet propaganda in U.S. government shortwave radio programs was Konstanty “Kot” Broel Plater, a Polish broadcaster hired in 1942 because of his previous experience in radio and journalism acquired both in pre-war Poland and as a war refugee in the United States during World War II. But while he wanted to help both his native country and America defeat Nazi Germany, he soon discovered that his superiors at the U.S. government radio station also expected him to be a propagandist for Soviet communist dictator Josef Stalin. Many of them believed in Stalin’s propaganda lies and assumed that like most other VOA broadcasters Broel Plater would read them on the air without any questioning. He, however, refused to repeat obvious lies and resigned from the Voice of America in 1944 although at the time the real reason for his resignation was not made public either by him or his employer.

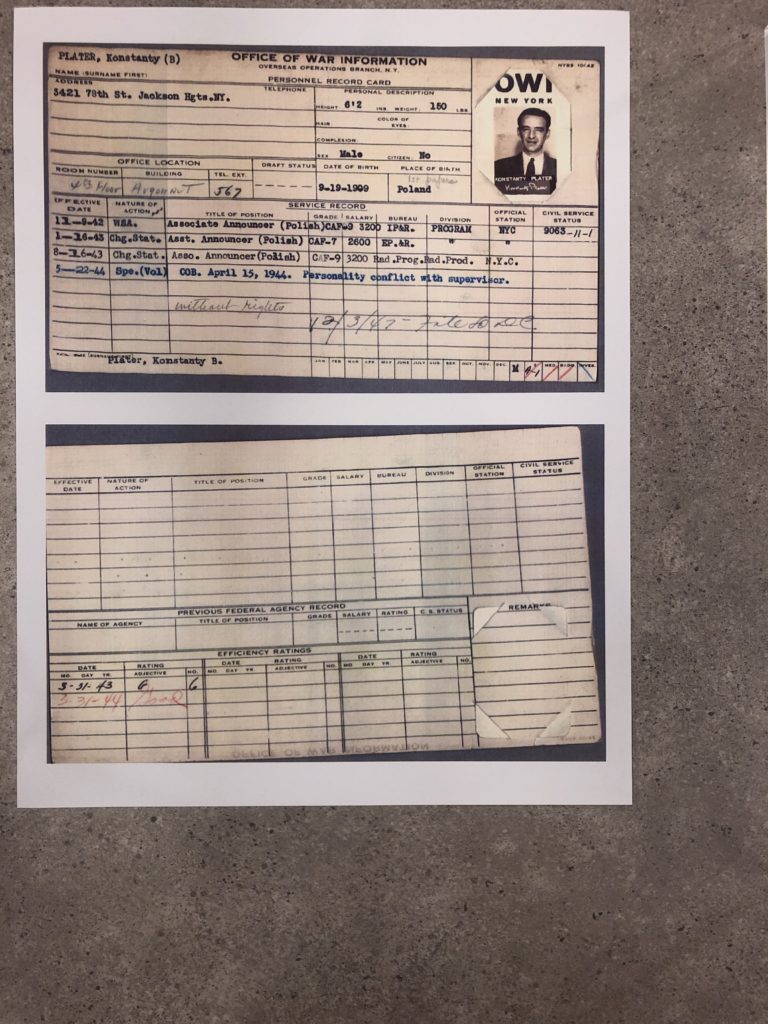

At the time of his resignation from the Voice of America, the Soviet Union was a war ally against Germany. The Polish Government-in-Exile, for which Broel Plater had worked as a diplomat before joining VOA, was also a U.S. ally in the anti-Nazi coalition, but militarily Poland was not anywhere near as important in the war effort as Stalin’s Russia. Konstanty Broel Plater told a Polish-American journalist Teofil Lachowicz in 2000, seven years before his death in 2007, that an official from his U.S. government agency, the Office of War Information (OWI), came from Washington to New York, where Voice of America radio studios were located at that time, to ask him whether he intended to continue his fight with the president of the United States and the director of the Voice of America. The VOA director could have been either John Houseman or his successor Louis G. Cowan, but both of them protected communist journalists and encouraged propaganda broadcasts in favor of the Soviet Union. The VOA director at the time of Broel Plater’s resignation was Louis G. Cowan.

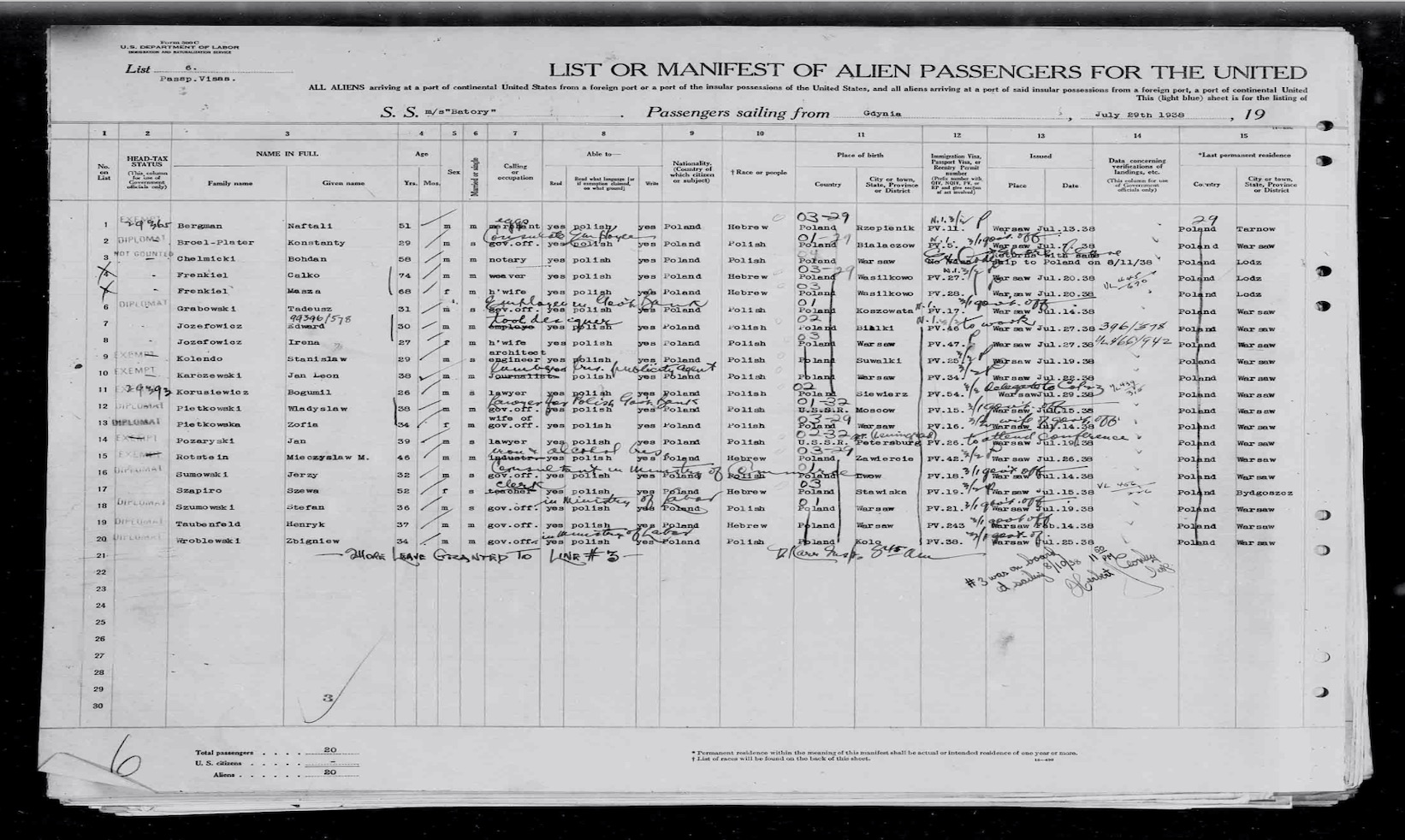

When World War II started on September 1, 1939, Konstanty Broel Plater was a young Polish diplomat who a year earlier had arrived in the United States to start his career. He came from an old and distinguished aristocratic Polish family of German origins which had settled in Poland many centuries ago. His family traditions and patriotic upbringing in pre-war independent Poland may explain why among dozens of Voice of America World War II Polish broadcasters and hundreds of other VOA journalists, Konstanty Broel Plater was probably the only one who had resigned in protest against the station’s pro-communist propaganda promoted by its management and fellow traveler journalists who were sympathetic toward communism and Soviet Russia. Their unquestioning support for the Soviet Union and for Stalin was naive to say the least since Russia helped Hitler start World War II with an unprovoked invasion of Poland in September 1939 and the Soviet dictator was also a mass murderer, but most radically left-leaning Voice of America officials and journalists ignored such facts.

Konstanty Broel Plater was one of the very few among wartime VOA broadcasters and Office of War Information employees who had resisted using Soviet propaganda. Another journalist who alerted his superiors to Soviet propaganda was Julius Epstein, a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany. He did not resign but lost his job in 1944 under a pretext of staff reductions. He was most likely dismissed for his criticism of Stalin’s admirers at the agency. The Office of War Information official slogan was “Truth Is Our Strength.” 1

In one of many twists and ironies of history, the same Voice of America which initially had supported Stalin’s takeover of Poland became during the Cold War together with Radio Free Europe one of the major forces for peaceful defeat of communism in East-Central Europe. It took, however, immeasurable suffering of millions of people forced to live under communism and nearly five decades to achieve this goal. An even greater irony is that some of the early Voice of America fellow traveler officials, including the first VOA director and later Hollywood actor John Houseman, and some of the early VOA journalists who provided propaganda help for Stalin’s efforts to enslave the East Europeans, are still lauded in VOA public relations online presentations as defenders of truthful journalism and press freedom 2 while truly brave journalists who stood up to both Hitler and Stalin like Broel Plater, Julius Epstein and a few others have been completely forgotten. 3

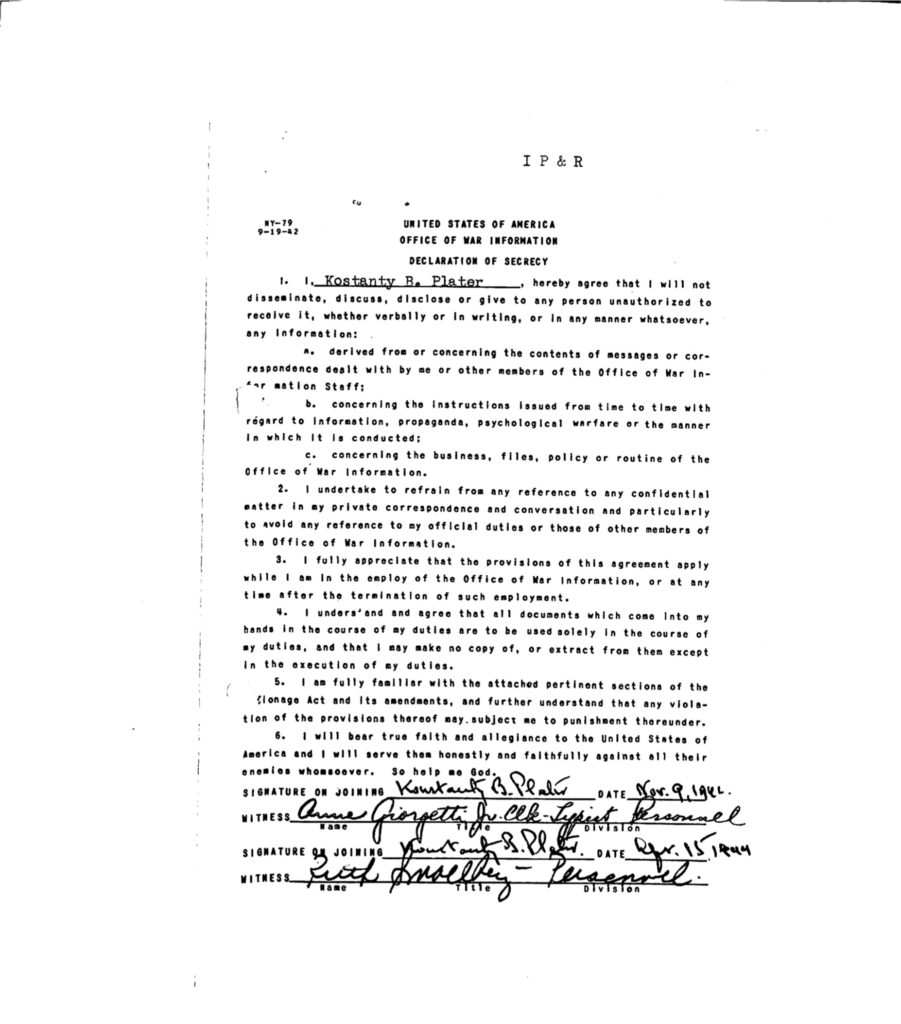

The Broel Plater family motto was Melior Mors Macula (Better Death Than Blemish). Participating in the big lie to cover up genocidal crimes of Soviet dictator Josef Stalin was not acceptable to this proud Pole even if the USSR and its communist leader were at that specific time invaluable allies of the United States in the war against Nazi Germany. Konstanty Broel-Plater knew that Stalin was not much different than Adolf Hitler and was in fact Hitler’s ally from 1939 until 1941 during which time the Red Army invaded and occupied not only eastern Poland but also Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, as well as parts of the territories of Finland and Romania . But because Soviet Russia was later helping America defeat Hitler, Plater resigned quietly and did not speak publicly about his dispute with Voice of America directors until very late in his life, although he sometimes mentioned it to members of his family and to some of his friends. His son, Prof. Zygmunt Plater, speculated to me in 2019 that his father may have felt bound by the secrecy clause of his employment contract with the Office of War Information(OWI), which was the federal agency in charge of Voice of America broadcasts during World War II.

Konstanty Broel Plater had many famous family ancestors. Some fought in Poland’s anti-Russian insurrections in the 19th century and made major contributions to preserving the country’s cultural heritage under foreign occupation. Count Tadeusz Broel Plater, was a marshal of the Polish-Lithuanian nobility in the district of Vilnius in Lithuania. He married Rachel Kosciuszko, niece of Tadeusz Kosciuszko, the famous Polish general and a hero of the American Revolution. Fleeing from the Russians, his sons settled in the 18th century in Australia. 4 Another family ancestor Emilia Plater, became famous and sometimes referred to as Poland’s Joan of Arc for fighting against the Russian occupiers in the failed November 1830 Uprising. The Broel Platers also produced other Polish and Lithuanian military leaders, politicians, entrepreneurs, and early photography and film pioneers in Poland. 5 Count Władysław Broel Plater founded the National Polish Museum in Rapperswil in Switzerland. Konstanty Broel Plater’s father was arrested by the Germans during World War I and threatened with execution—his life reportedly spared due to pleas from his wife who with Konstanty visited her husband in a German prison. 6

It was no surprise that as a refugee in the United States during World War II and a U.S. government radio broadcaster, and later as a political refugee from communism after the war, Konstanty Broel Plater would not compromise on defending the truth and resisting censorship. Noblesse oblige was part of the family tradition of public service and struggle for Poland’s independence. 7

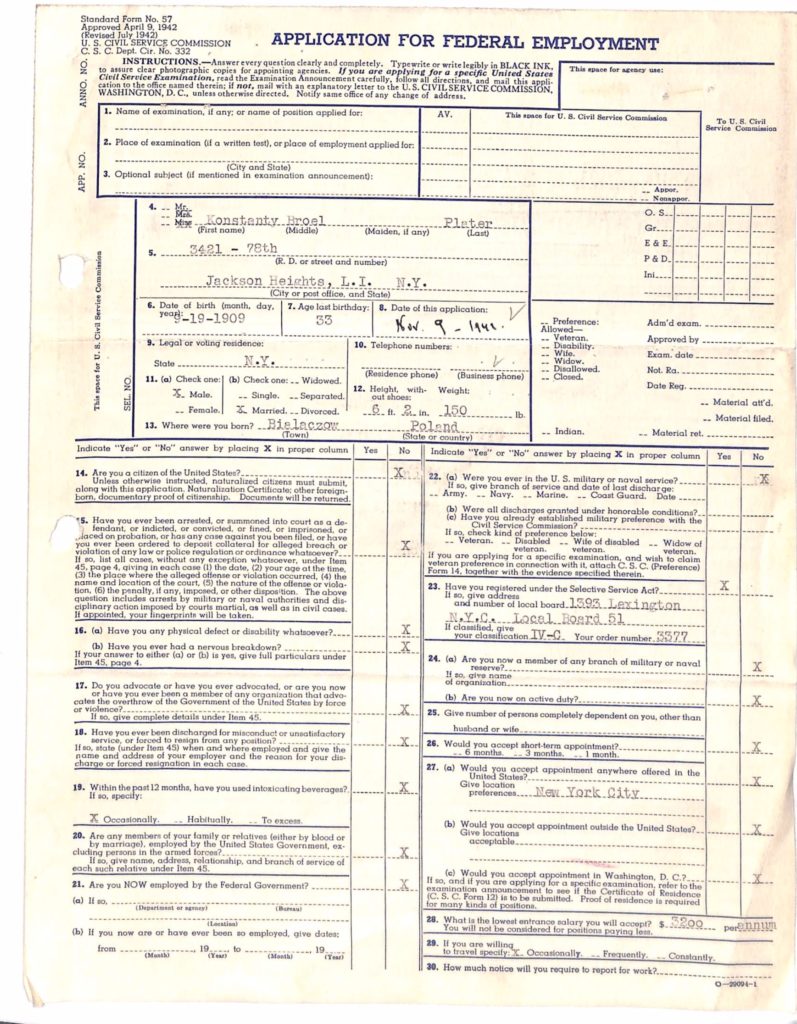

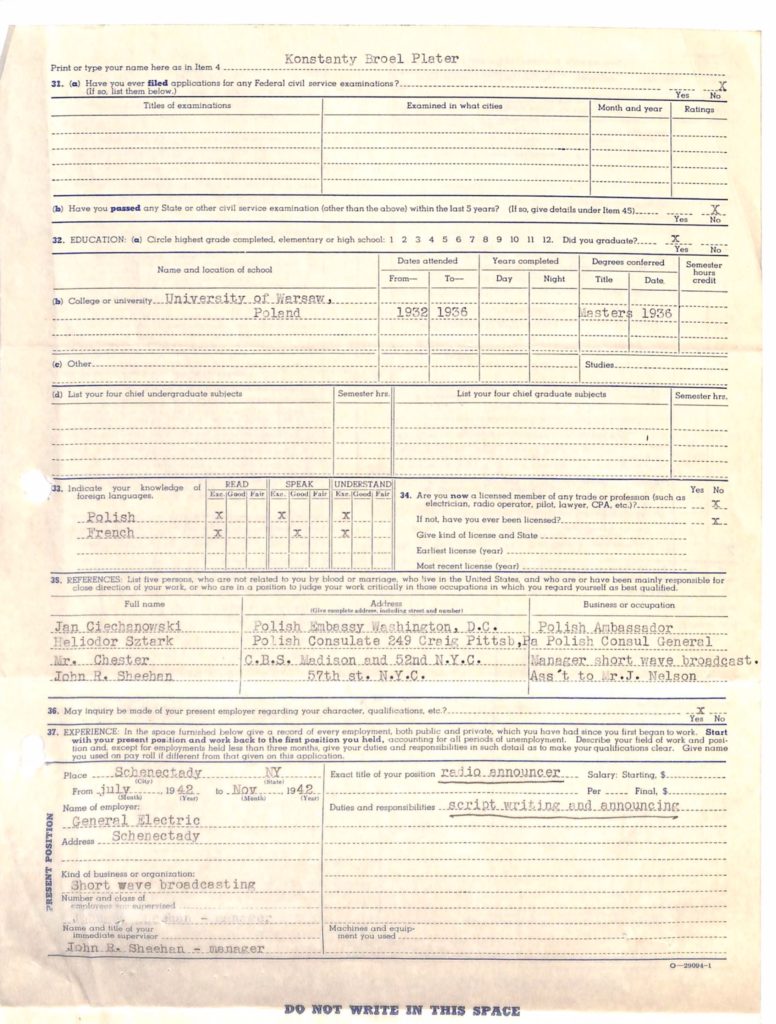

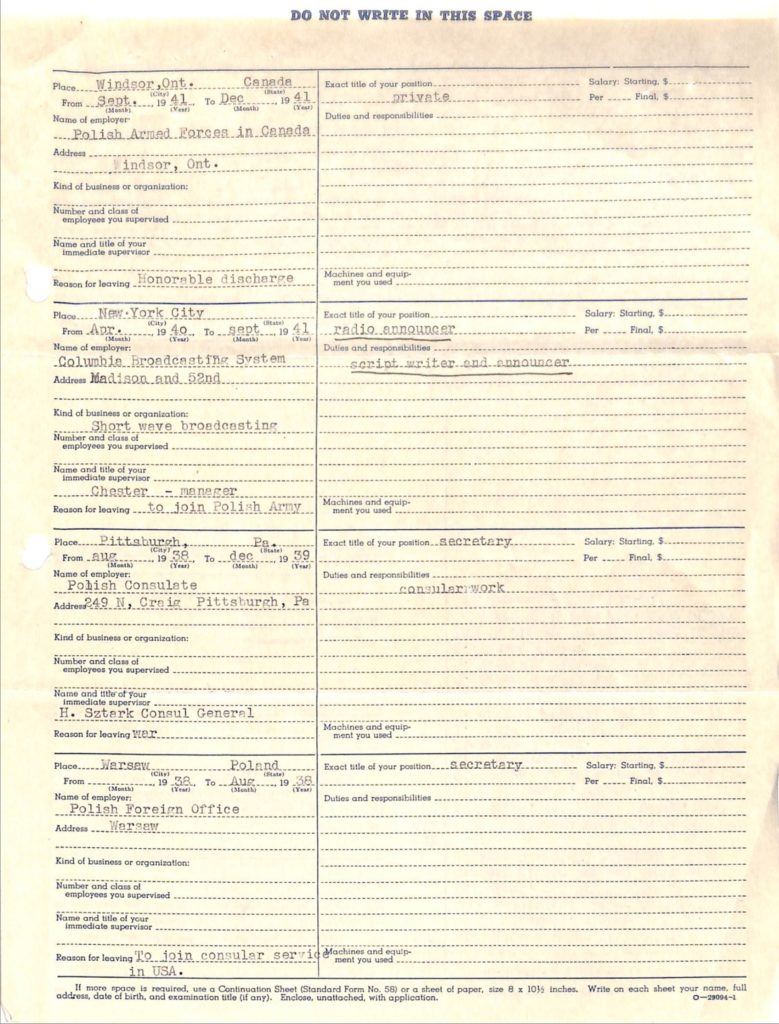

Konstanty Broel Plater grew up at the family estate in Białaczów during the years of Poland’s independence in the interwar period. After earning a law degree from the prestigious University of Warsaw in 1936, he joined the Polish diplomatic service in 1938 and was assigned the same year to the Polish Consulate in Pittsburg, PA. At the time, he spoke fluent French but practically no English. As a younger son who could not inherit the family estate, his professional choices were largely limited to becoming a priest or a diplomat.

Movie fans may be interested to know that the Broel Plater family’s former manor house in Białaczów, in central Poland, confiscated first by the Germans during World War II and by the Communists after the war, can be seen in the 2018 Oscar-nominated Cold War film by Paweł Pawlikowski whose film Ida won the 2015 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. In Cold War, the director included a short reference to Radio Free Europe (RFE), a radio station also U.S. funded, which—unlike the wartime Voice of America—never lied about communist crimes or tried to cover them up with Soviet propaganda.

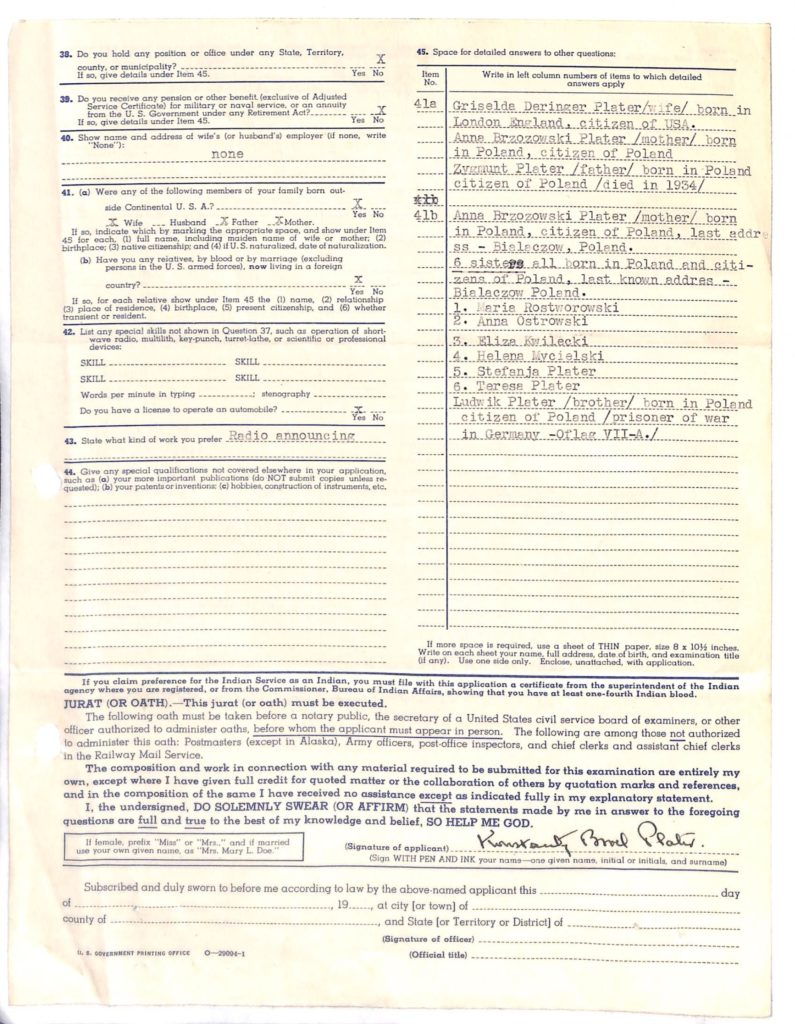

The Broel Plater family’s fortune in Poland was wiped out by World War II and communism. His father, Zygmunt Broel Plater, died in 1934. His mother, Anna Brzozowski Plater, and his six sisters, lived in poverty in Poland during the war although they could have claimed to be of German origin and receive privileged treatment. His older brother, Ludwik Plater, was a prisoner of war in Nazi Germany. One of his relatives, Maria Broel Plater, was a prisoner in the Ravensbrück German concentration camp where she was subjected to medical experiments by Nazi doctors.

Had the family been from the part of Poland occupied in 1939 by the Soviet Union, they would have faced deportations to the Gulag slave labor camps and his brother might have been executed in the Katyn Forest massacre. This was the fate of about 22,000 Polish military officers and Polish government employees who were murdered in the spring of 1940 by the NKVD Soviet secret police on the orders of Stalin and the Soviet Politburo, but information about such communist atrocities was carefully hidden by Soviet sympathizers and Communists working for the Voice of America during World War II. The Soviet Katyń massacre propaganda lie, accepted at face value and promoted by VOA officials and journalists was most likely the main cause of his resignation from VOA in 1944 although there is no document showing that it was the decisive factor.

Voice of America’s programs during World War II, when Konstanty Broel Plater worked there from late 1942 until April 1944, were quite different from Radio Free Europe’s and VOA’s broadcasts in support of freedom and democracy in the later years of the Cold War. During World War II, VOA, then operated under various names, functioned primarily as an anti-Nazi and anti-Japanese U.S. government propaganda radio station, but its pro-Soviet officials and journalists also turned it into a propaganda outlet on behalf of Stalin and supported in their broadcasts Soviet takeover of East-Central Europe. VOA’s first chief news writer was Howard Fast, an American communist writer and future winner of the 1953 Stalin Peace Prize. Fast was in charge of VOA English news during some of the time Broel Plater worked there as a Polish-language announcer in the Overseas Branch of the Office of War Information. Some of the members of the VOA Polish desk and other Office of War Information units specializing in producing propaganda targeting Poland and Polish speakers were radical socialists, some of whom later worked as anti-American propagandists for the regime imposed on Poland by the Soviets.

Konstanty Broel Plater was one of the few early VOA journalists who were not admirers of the Soviet Union or fooled by Soviet propaganda. Not willing to compromise on journalistic truth, he would not keep his VOA job for too long. In 1942 Soviet Russia was already America’s valuable military ally in the war against Nazi Germany when Stalin’s earlier alliance with Hitler collapsed with Germany’s attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, but as Broel Plater discovered, VOA’s pro-Soviet propagandists went much further in promoting Stalin’s interests than even what the already strongly pro-Russia Roosevelt administration, including top U.S. diplomats and military readers, wanted VOA journalists to be. The Supreme Allied Commander and future U.S. President, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, accused early VOA officials and broadcasters of “insubordination” even toward President Roosevelt, but he wrote his assessment of the wartime Voice of America much later, a few years after leaving the White House. 8

After Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union attacked and occupied Poland in 1939 under the secret terms of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, also known as the Hitler-Stalin Pact, Broel Plater was still working as a low-ranking diplomat in the United States. He joined the units of the Polish Army being formed in Canada by the Polish Government-in-Exile based in London, but the military recruitment project in Canada was quickly abandoned due to the lack of sufficient number of Polish-Canadian and Polish-American volunteers. The bulk of the Polish Armed Forces in the West loyal to the democratic Government-in-Exile was formed in the Middle East with volunteers who had survived the Soviet Gulag prison camps. When Broel Plater pointed out to his superiors in the Polish Government in Exile that Canadian-American and Polish-American young men will opt for joining their own countries’ armed forces rather than joining the Polish Army in the West, he was met with criticism, but he had shown that he was not afraid to speak his mind and tell the truth to his superiors in the Polish Embassy. He did the same at the Voice of America.

As still a young man, Broel Plater wanted to fight against Nazi Germany. He served as a private in the Polish Army in Canada from September 1941 to December 1941. After the Polish units in Canada were disbanded, he returned to the United States and married Griselda Deringer, an American woman born in London, England, whom he had met earlier while working for the Polish Consulate in Pittsburg. During their courtship they spoke French because his English was still limited. She was the love of his life.

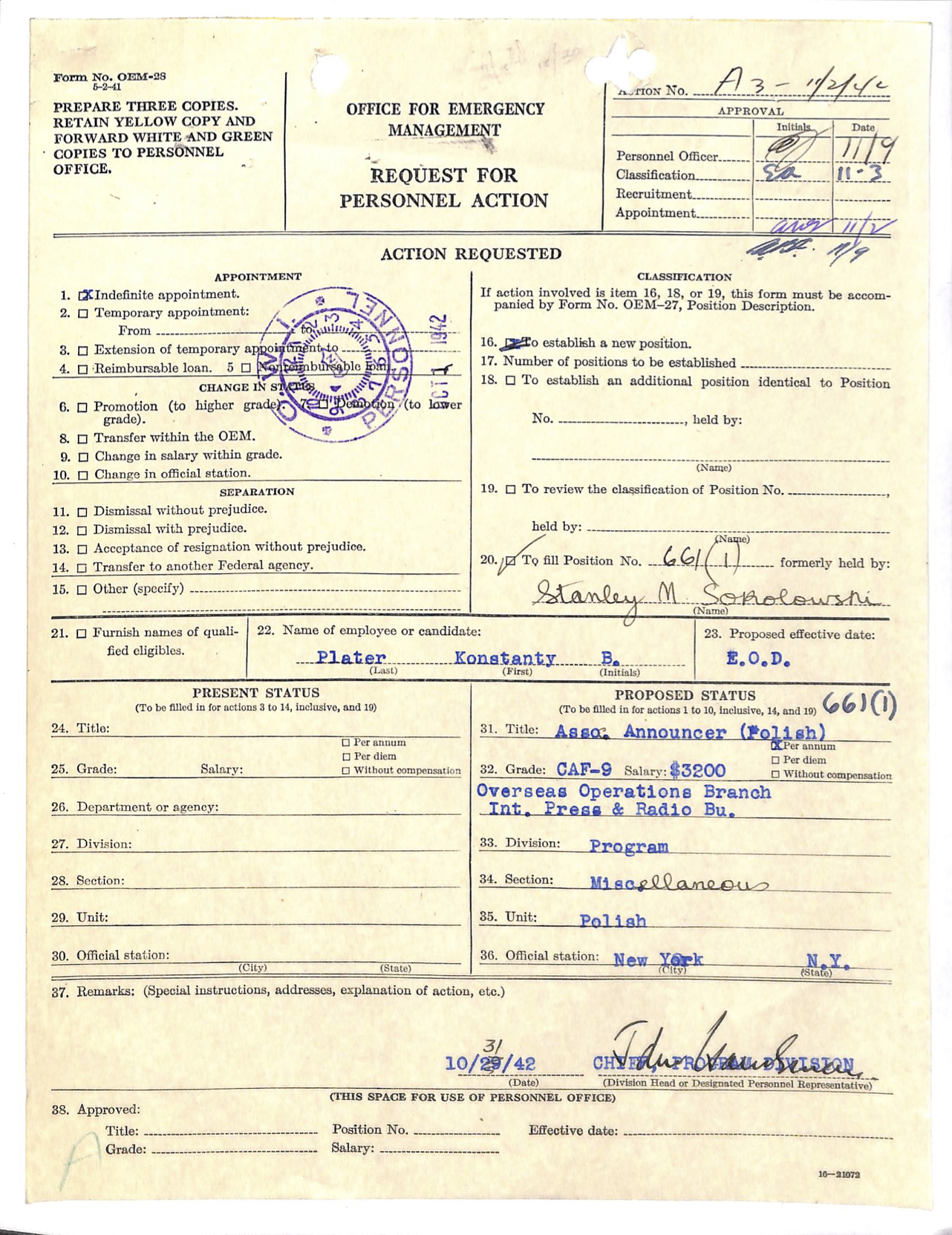

With his entry-level diplomatic job in the United States lost due to wartime budget cuts, he found work as a radio writer and announcer for Polish-language programs aired by General Electric and CBS. Already in Poland before the war he had experimented with journalism, photography and remote live radio broadcasting. Because of his radio experience and language skills, he was hired by the U.S. government on November 9, 1942 to work as a Polish-language announcer in the Office of War Information where what later became known as Voice of America shortwave radio broadcasts originated. One of his hiring documents, a Request for Personnel Action dated October 31, 1942, was signed by Program Division Chief John Houseman who was later declared to be the first VOA director.

John Houseman was quietly forced out in 1943 after Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles warned the FDR White House in a secret memo that he was hiring Communists, but many of the VOA broadcasters he had hired kept their jobs until at least the end of the war. 9 They made it impossible for anti-communists like Broel Plater to continue working for the Voice of America. At the time of his resignation in April 1944, the Voice of America director was Louis G. Cowan who a few months earlier wrote a glowing letter of recommendation for departing VOA news chief Howard Fast, a best-selling author of historical novels soon to become editor of the Communist Party USA newspaper, a Communist Party member, and later a recipient of the 1953 Stalin Peace Prize. 10

John Houseman, a radio and theatre producer, was a fellow traveler Soviet sympathizer who usually recruited his Communist friends and associates for VOA jobs. Prior to becoming Voice of America director, he and Orson Welles caused a considerable amount of panic in much of the United States with their 1938 Mercury Theatre on the Air production of H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds which mixed genuinely sounding but fake evening radio news bulletins with dramatic descriptions of an alien invasion. Houseman obviously made a mistake in hiring an aristocratic Pole with former ties to the Polish Government in Exile, with which Stalin would break diplomatic relations in April 1943 after the Katyn massacre of thousands of Polish POW military officers was revealed and VOA under Houseman’s successors would start covering up the Soviet atrocity by blaming it on the Germans. 11 Konstanty Broel-Plater found himself working in New York among American and foreign Communists, including some like Stefan Arski, also known as Artur Salman, who would later serve Soviet-dominated communist regimes in Eastern Europe after the war as propagandists and diplomats. 12

The presence of Soviet agents of influence combined with Konstanty Broel Plater’s uncompromising commitment to the truth led to conflicts with his supervisor and his eventual voluntary resignation from the Voice of America on April 15, 1944. In 2000, he told a Polish-American newspaper reporter that some of the translators hired to work in the VOA Polish Service had a poor knowledge of Polish which required him to make on-air corrections. When he also realized that VOA centrally-prepared programs were filled with Soviet propaganda, he complained to the Office of War Information in Washington. According to Broel Plater, an OWI official took him to lunch and “in a short conversation asked him if he plans to fight against the President of the United States and the Voice of America Director?”

Nad Berlinem pojawiły się samoloty harcerskie, które zrzucały na miasto pochodnie…”

As a example of nonsensical Polish texts he sometimes received to read on the air and had to correct on the fly, he gave the Polish-American interviewer the following sentence: “Nad Berlinem pojawiły się samoloty harcerskie, które zrzucały na miasto pochodnie…” Translated back into English, the sentence read: “Boy scout planes appeared over Berlin and dropped torches over the city…” Whoever translated such a text from English into Polish could not have been a native Polish speaker.

Przybyły stamtąd wysłannik zaprosił go na lunch do restauracji i w krótkiej rozmowie zapytał, czy zamierza walczyć z prezydentem Stanów Zjednoczonych i dyrektorem Głosu Ameryki?

The person sent [from Washington] took him to lunch at a restaurant and in a short conversation asked whether he intends to fight with the president of the United States and the Voice of America director.

Mimo tej zawoalowanej groźby Konstanty Plater swoimi sposobami starał się jednak walczyć z coraz bardziej nasilającą się prosowiecką propagandą uprawianą przez rozgłośnię.

Despite this veiled threat, Konstanty Plater in his own ways tried to struggle with the radio station’s intensifying pro-Soviet propaganda.

W efekcie stwarzano mu coraz gorsze warunki pracy (możliwość pracy tylko w nocy, ograniczenie wypowiedzi jedynie do anonsowania programu), by w końcu doprowadzić do sytuacji, kiedy to sam poprosił o zwolnienie, co zbiegło się z zakończeniem wojny.

As a result, working conditions were made worse for him. He was allowed only to work at night and limited to only announcing the program. 13

“He was very humble, he stressed his [aristocratic] title didn’t mean much to him. When he started working at the paper mill, his co-workers teased him about being a count,” his Polish-American neighbor Elżbieta Palms recalled from her conversations with Mr. Plater. He gave his three children Polish names: Zygmunt, Marek Ludwik, Stefania Anna.

Elżbieta Palms who graduated from the University of Warsaw where she studied German philology and emigrated to the United States in 1987 met Konstanty Plater in 2000 through one of her colleagues who was friends with his wife Griselda.

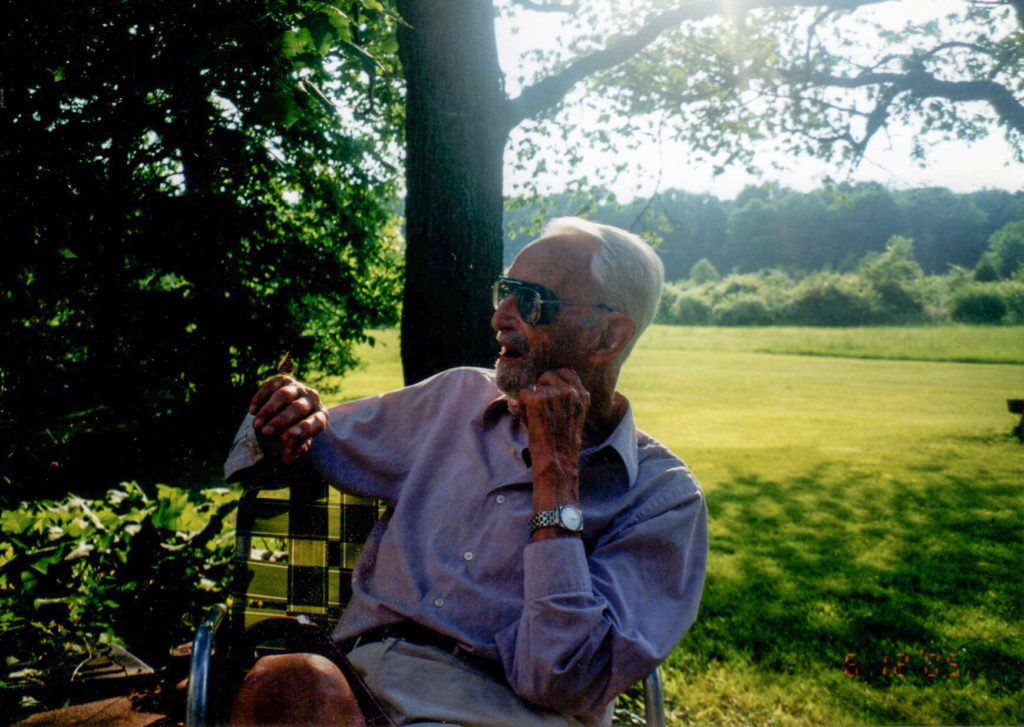

She gave him my phone number, and Mr. Plater called me immediately. I remember he started in English, but when I suggested switching to Polish he was delighted. His Polish was a cultivated, old fashioned, from the 30’s (he graduated from UW [University of Warsaw] with a degree in law). He didn’t have many opportunities to speak Polish anymore, he told me. He invited me to his old farm in Kintnersville, and I remember spending an entire afternoon listening to his stories. But when I asked if he kept a journal [or] wrote down his memoirs his response was: “O, droga Pani, moje życie było tak mało zajmujace, kogoż by to moglo zainteresować?” [My dear lady, my life was so unremarkable, who would be interested?] …And he continued talking about his meeting J.I. Paderewski in Pittsburgh, etc. At 91, Mr. Plater was mentally and physically in an amazing shape. He was still on the tractor cutting grass on the huge meadows around his house, knew the latest books by Norman Davies, and just learned computer in order to stay in touch with his family in Poland, and many cousins throughout the world. 14

I then decided to do something to preserve his stories. Teofil Lachowicz was then working for the SWAP Archives and published many articles about Polish veterans. Kot (Mr. Plater insisted we call him Kot) agreed to an interview, and a 2-part story was published in Nowy Dziennik (Przeglad Polski) in 2000 (also included in Tolek’s book “Dla Ojczyzny ratowania…”, Łódź, 2007). We continued visiting him on the farm, Alicja, Tolek and myself. We would cook/bake something Polish and bring with us for a lunch outside on the patio. His favorite was buckwheat kasha with gulash and “mizeria” [cucumber salad]. He always had a big jar of cold water mixed with honey from his own bee hives (“I have 3,000 females working for me day and night”). He loved sharing his life stories with us, singing Polish songs (“O mój rozmarynie”…etc). Just being able to speak Polish was such a joy to him. He was also very interested in our lives, and was delighted to hear that my son was fluent in Polish. He insisted that I bring Daniel with me which I did. They had a lively conversation which must have impressed my son (then [perhaps] 15) because he still remembers Kot. We became familiar with Kot’s many family pictures and stories. We also met Marek, his youngest son, who lived 1/2 hr away, and came to see/help his Dad daily. We met Zygmunt and Steni at the funeral (June, 2007).Kot is buried together with his wife in Ottsville, a beautiful old cemetery. We visit him on our way to Czestochowa, near Doylestown.

Konstanty Broel Plater’s son, Zygmunt J. Broel Plater, is a well-known American professor of environmental law and author of legal textbooks. He was lead counsel in the extended endangered species litigation over the Tennessee Valley Authority’s Tellico Dam, representing the endangered snail darter, farmers, Cherokee Indians, and environmentalists in the Supreme Court of the United States, federal agencies, and congressional hearings. In 2019, he shared with me on the phone and by e-mail these recollections of what his father told his family about his work for the Voice of America in the Office of War Information.

I should note also that my father never cited Katyn as having been specifically mentioned in his resignation event. He often talked of false OWI news texts lauding the benign nature of Russian actions in the war, overlooking atrocities, and he often told us of his conviction, long before it was established as true, that it was Russians rather than Nazis who massacred the Polish thousands in the Katyn Forest. But I cannot say that I ever heard him specify that OWI texts had actively falsified the Katyn story, though I suspect they certainly did so, and he probably was present for that falsification. He explained that when he complained of the Russian propaganda infecting so much of what his office was broadcasting, “his boss” said he had to realize that “the Roosevelts” were on very friendly terms with Russia, and so OWI had to adjust accordingly. 15

Elżbieta Palms was able to provide me with a few more details about Konstanty Broel Plater’s disagreement with the Voice of America management and his two visits to Poland when the country was still under communist rule. She wrote that “meeting Kot was like a glimpse into a magical garden, into the best of Polish history, a past no longer existing, but brought back to life by his stories.”

Another striking characteristic was Kot’s faith. God was everywhere, always present, in the simple flower garden he still took care of, in the majestic linden trees he planted himself in front of the house (“because the scent of their flowers reminds me of Białaczów” [his family’s home in Poland]).

He could not return to communist-ruled Poland after the war and continued to live in the United States as a political refugee, eventually becoming a U.S. citizen. When he visited homeland still under communism as an American citizen, he was subjected to humiliating searches at the Warsaw airport.

Mr. Plater mentioned working for VOA a few times (also recorded in Tolek’s [Teofil Lachowicz] article). It was in the context of his life experiences. I remember well, that he mentioned being asked to read some “lies” about Poland, and he refused to do it. He got up and walked out.

I am not sure exactly what the topic was, maybe Katyń? Mr. Plater was appalled by the degree of the VOA’s directors servile behavior toward the Soviets. It was so obvious he couldn’t stand working there anymore.

He had no illusions about the communism and the government in Poland. His family in Poland suffered persecution, his mother, his sisters (especially Helena who died in 2008 http://www.stowbial.pl/news.php?readmore=56). Even though he struggled financially himself, there were many care packages sent to Poland. I especially remember the story about how his British wife and the three kids spent hours gathering certain herbs on the meadows and in the woods. Those were then sold to companies that produced herbal/medical supplements, and the money used to send packages to Poland. Many were stolen, or items were purposely damaged, but it didn’t stop him.

Mr. Plater visited Poland twice, still under the communistic regime, and unfortunately went through some kind of “special treatment” at the airport in Warsaw. “Poor customs clerks, they probably had received specific instructions how to treat enemies of the people”. 16

Konstanty Broel Plater’s decision to leave a relatively well-paying U.S. government job created a hardship for him and his family, but for a man of principle, it was the only possible way of responding to Soviet propaganda lies in Voice of America programs. For several years after leaving VOA, he had worked as a laborer at a paper mill before getting a technician’s job in the factory’s laboratory. He also restored an old farmhouse in Pennsylvania and raised a family. His wife, Griselda Deringer Plater died in 1986. Konstanty Broel Plater died in 2007.

His son, Prof. Zygmunt J. Broel Plater, had this comment about his father’s conflict with the Voice of America and possible lessons for Americans concerned about actions of the Russian government under President Vladimir Putin’s rule.

This is a chastening history that rings true for my siblings and me. Our father, Konstanty Broël Plater, was a broadcast announcer for OWI’s Polish service. He repeatedly tried to tell the US managers for OWI that the American radio broadcasts to Poland were being written by Soviet sympathizers covering up Communist horrors like the mass killing of 20,000 Polish officers in the Katyn Forest. The bosses told him they “were sorry, but Mr. Roosevelt wanted it this way.” Dad resigned in deep frustration. Sadly, the KGB was able to continue its Soviet misinformation in American media for long after the war. And even more sadly, we now have a KGB genius totally manipulating a far less intelligent but equally-duped American president more drastically than Stalin ever thought possible. When asked in Helsinki whether he rejected Russian actions to switch the 2016 US election, Trump replied “President Putin, he just said it’s not Russia. I will say this: I don’t see any reason why it would be.” But it’s obvious why it would be: Once more, Russia wants to advance itself by undercutting America, working by proxy to tear America apart. In its current Putin incarnation, the KGB is winning once again. 17

Notes:

- Julius Epstein, a Jewish refugee journalist from Austria who himself had a brief infatuation with communism during his student days in Germany, wrote after the war that when in 1942 [he] “entered the services of what was then the ‘Coordinator of Information’ which became after a few months the O.W.I., I was immediately struck by the fact that the German desk was almost completely seized by extreme left-wingers who indulged in a purely and exaggerated pro-Stalinist propaganda.” Stalin was then our “gallant ally,” Epstein, who became a fierce critic of the Voice of America, explained in his 1951 article calling for reforms to improve countering of Soviet propaganda and disinformation. See: “How a refugee journalist exposed Voice of America censorship of the Katyn Massacre,” Cold War Radio Museum, April 16, 2018, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/how-refugee-journalist-exposed-voice-of-america-katyn-censorship/.

Julius Epstein, “The O.W.I. and the Voice of America,” a reprint from the Polish American Journal, Scranton, Pennsylvania, 1951.

Julius Epstein, Executive Session, September 19, 1952, Hearings Before the Select Committee to Conduct An Investigation of the Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre, 25-16. Julius Epstein, Executive Session, September 19, 1952, Hearings Before the Select Committee to Conduct An Investigation of the Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre, 47-48. ↩

- Voice of America, Past VOA Directors: John Houseman (1942-1943),” July 16, 2018, https://www.insidevoa.com/a/john-houseman-1942-1943/4485185.html. Also see: Michelle Harris, “Directors Reflections: John Houseman,” February 22, 2012, Voice of America, https://www.insidevoa.com/a/john-houseman-140370173/177535.html. Inside VOA, “VOA History,” May 8, 2019, https://youtu.be/YjLgcaRc8Po. ↩

- Epstein, Julius. Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 81st Congress, Second Session, Appendix. Part 17 ed. Vol. 96. August 4, 1950, to September 22, 1950. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1950, A5744-A5745. See: Cold War Radio Museum, ‘Love for Stalin’ at wartime Voice of America, October 6, 2016, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/love-for-stalin-at-wartime-voice-of-america/. ↩

- Cumberland Argus, “The Platters of Parramata,” June 11, 1926, http://www.zrobtosam.com/PulsPol/Puls3/index.php?sekcja=1&arty_id=2029. ↩

- Katarzyna Jedynak, “Z dziejów ziemiaństwa znad Kamiennej: rodzina Broel-Platerów z Białaczowa i jej związki z Bliżynem na przełomie XIX i XX wieku,” O. PTH Skarżysko-Kamienna – Muzeum Martyrologii Wsi Polskiej w Michniowie, 2014, http://bazhum.muzhp.pl/media//files/Z_Dziejow_Regionu_i_Miasta_rocznik_Oddzialu_Polskiego_Towarzystwa_Historycznego_w_Skarzysku_Kamiennej/Z_Dziejow_Regionu_i_Miasta_rocznik_Oddzialu_Polskiego_Towarzystwa_Historycznego_w_Skarzysku_Kamiennej-r2014-t5/Z_Dziejow_Regionu_i_Miasta_rocznik_Oddzialu_Polskiego_Towarzystwa_Historycznego_w_Skarzysku_Kamiennej-r2014-t5-s53-64/Z_Dziejow_Regionu_i_Miasta_rocznik_Oddzialu_Polskiego_Towarzystwa_Historycznego_w_Skarzysku_Kamiennej-r2014-t5-s53-64.pdf ↩

- The Morning Call, “Konstanty B. Plater,” June 17, 2007, https://www.mcall.com/news/mc-xpm-2007-06-17-3725551-story.html. ↩

- Lech Paszkowski, Poles in Australia and Oceania 1790-1940, Australian National University Press , 1987, http://duffus.com/count_plater.htm. ↩

- Ted Lipien, “First VOA Director was a pro-Soviet Communist sympathizer, State Dept. warned FDR White House,” Cold War Radio Museum, May 5, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/state-department-warned-fdr-white-house-first-voice-of-america-director-was-hiring-communists/. Ted Lipien, “General Eisenhower accused WWII VOA of ‘insubordination’,” Cold War Radio Museum, May 14, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/general-eisenhower-accused-wwii-voa-of-insubordination/. Footnote in “Waging Peace” by Dwight D. Eisenhower: “During World War II the Office of War Information had, on two occasions in foreign broadcasts, opposed actions of President Roosevelt; it ridiculed the temporary arrangement with Admiral Darlan in North Africa and that with Marshal Badoglio in Italy. President Roosevelt took prompt action to stop such insubordination.” Dwight D. Eisenhower, The White House Years: Waging Peace 1956-1961 (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1965) 279. ↩

- The memorandum about Soviet and communist influence within the wartime Voice of America, signed off with a cover memo by Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, a distinguished career diplomat and a major foreign policy advisor to President Roosevelt and his personal friend, was forwarded to the White House with the date, April 6, 1943. The attached memorandum with the addendum listing names of individuals who had been denied U.S. passports for government travel abroad was dated April 5, 1943. One of them was John Houseman. The documents were declassified in the mid-1970s and have been accessible online for some time from the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum Website and the National Archives. It appears, however, that they have never been widely disclosed and analyzed before now. They are presented for the first time with a historical analysis on the Cold War Radio Museum website. Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles April 6, 1943 memorandum to Marvin H. McIntyre, Secretary to the President with enclosures, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum Website, Box 77, State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944; version date 2013. State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944, From Collection: FDR-FDRPSF Departmental Correspondence, Series: Departmental Correspondence, 1933 – 1945 Collection: President’s Secretary’s File (Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration), 1933 – 1945, National Archives Identifier: 16619284. ↩

- Louis G. Cowan also held radically leftist views and pro-Soviet propaganda continued in VOA broadcasts under his directorship during the war. On January 21, 1944, he wrote a glowing recommendation letter for Howard Fast, the future recipient of the Stalin Peace Prize, in which he stressed that accepting his resignation was “pure compliance with your wish — not at all what we want.”

“…what a fine job you have done for this country, the OWI, and the Radio Bureau [the Voice of America] in particular….Please accept my own sincere thanks and with that the gratitude of an organization and a cause well served.”

Louis G. Cowan ended his letter to Howard Fast with a note that he was being greateful for his service at the Voice of America, not only on his own behalf but also on behalf of Office of War Information Director Elmer Davis, Overseas Bureau directors Robert E. Sherwood and Joseph Barnes, and former VOA Director John Houseman. Many people at the agency “have been inspired by your sincerity and your achievement,” Cowan added. See: Howard Fast, Being Red (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), 25. ↩

- The bipartisan Select Committee to Conduct an Investigation and Study of the Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre, also known as the Madden Committee after its chairman Ray J. Madden (D-IN), said in its final report issued in December 1952: “In submitting this final report to the House of Representatives, this committee has come to the conclusion that in those fateful days nearing the end of the Second World War there unfortunately existed in high governmental and military circles a strange psychosis that military necessity required the sacrifice of loyal allies and our own principles in order to keep Soviet Russia from making a separate peace with the Nazis.” The committee added: “For reasons less clear to this committee, this psychosis continued even after the conclusion of the war. Most of the witnesses testified that had they known then what they now know about Soviet Russia, they probably would not have pursued the course they did. It is undoubtedly true that hindsight is much easier to follow than foresight, but it is equally true that much of the material which this committee unearthed was or could have been available to those responsible for our foreign policy as early as 1942.” The Madden Committee also said in its final report in 1952: “This committee believes that if the Voice of America is to justify its existence, it must utilize material made available more forcefully and effectively.” A major change in VOA programs occurred, with much more reporting being done on the investigation into the Katyń massacre and other Soviet atrocities, but later some of the censorship returned. Radio Free Europe (RFE), also funded and indirectly managed by the U.S., never resorted to such censorship, and provided full coverage of all communist human rights abuses. See: Select Committee to Conduct an Investigation and Study of the Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre, The Katyn Forest Massacre: Final Report (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1952), 10-12. The report is posted on the National Archives website: https://archive.org/details/KatynForestMassacreFinalReport. ↩

- At least two World War II Voice of America journalists who earlier had held key positions in the Polish Service (Stefan Arski, a.k.a Artur Salman and Mira Złotowska), and the Czechoslovak Service (service chief Dr. Adolf Hoffmeister), went to work for communist regimes after the war. In 1947, Arski became an influential anti-U.S. propagandist for the communist regime in Poland, while Hoffmeister was Czechoslovak Ambassador to France from 1948 to 1951. ↩

- Teofil Lachowicz, “Zapomniany dyplomata,” Przegląd Polski (New York), October 20, 2000. ↩

- Elżbieta Palms’ e-mail to Ted Lipien, April 29, 2019. ↩

- Zygmunt Broel Plater e-mail to Ted Lipien, April 26, 2019. ↩

- Elżbieta Palms’ e-mail to Ted Lipien, May 5, 2019. ↩

- Comment posted online by Prof. Zygmunt Broel Plater, February 2020. ↩