Updated: January 2024

A State Secret

Polish children from World War II Santa Rosa refugee camp, Guanajuato, Mexico. Source: Embajada de Polonia en México, Wikipedia. The date and photographer are unknown. CC BY 3.0.

How the Roosevelt Administration Shipped Polish Refugee Orphans to Mexico In Locked Trains and Lied About It to Protect Stalin

The Untold Story of Polish Refugee Children from Soviet Russia: “A Group Lost in History”

By Ted Lipien

The current crisis at the Voice of America (VOA), where some government employees of the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM) post images on their personal Facebook pages calling for the violent destruction of the Jewish state and in their VOA news reports refuse to call Hamas “terrorists,” may serve as a reminder of a different and now almost wholly forgotten episode of World War II history involving refugee children, the Roosevelt administration, and U.S. government propaganda. It is a story of the U.S. government’s illegal secret censorship of domestic media. It has Americans being deceived about Russia by their government. It is about secret collusion with a foreign power. It describes Polish orphans who had escaped from Russia being kept behind a barbed wire fence of a former detention center for Japanese Americans and being transported under U.S. military guard to Mexico in locked trains. It is a story that was never honestly reported by the Voice of America (VOA), the U.S. government’s official radio station established in 1942 to broadcast news to the world.

A propaganda sticker produced by the U.S. Office of War Information (OWI), which, in addition to its own foreign and domestic propaganda, also managed radio broadcasts for overseas audiences later known as the Voice of America.

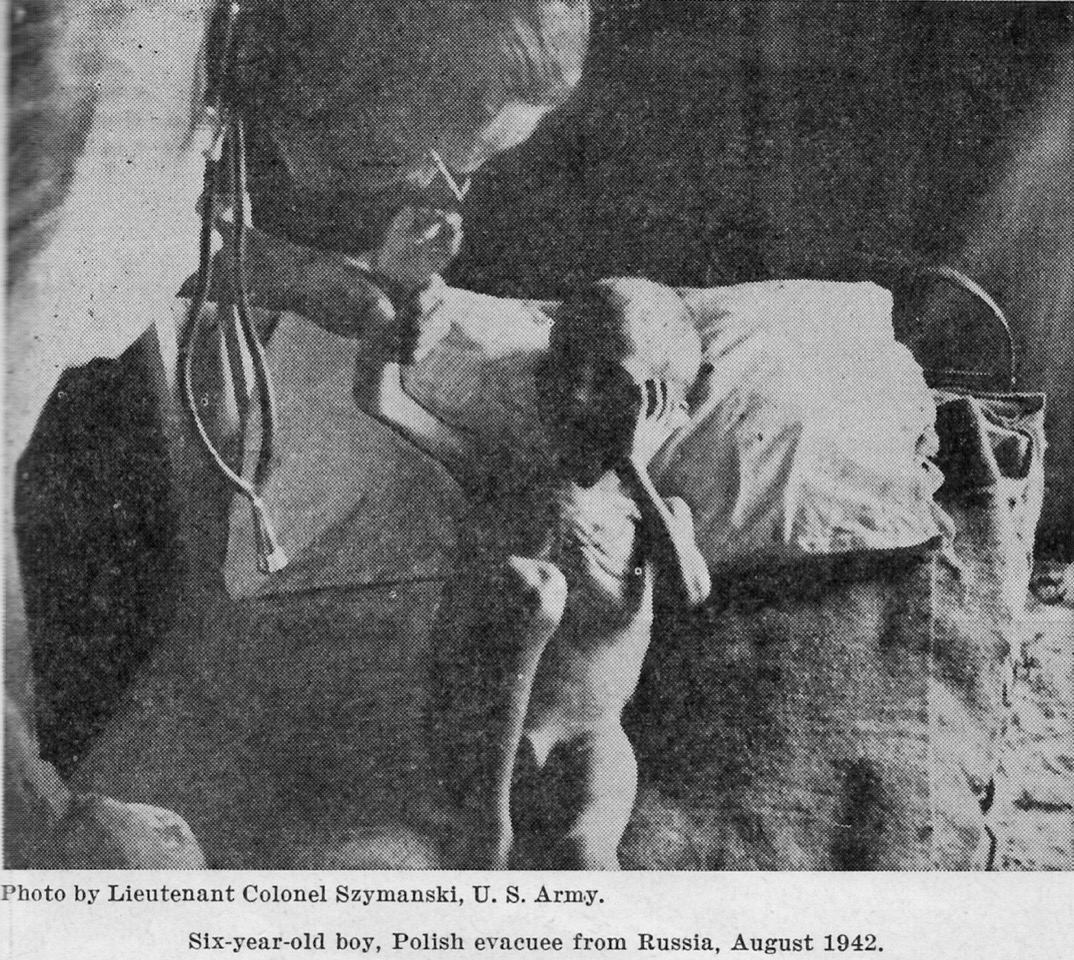

Three sisters, ages 7, 8, and 9, were Polish evacuees from Russia in August 1942. Photo by Lieutenant Colonel Szymanski U.S. Army, which remained classified until 1952. The Katyn Forest Massacre. Hearings Before the Select Committee to Conduct An Investigation of the Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Foreign Massacre. Eighty-Second Congress, Second Session on Investigation of the Murder of Thousands of Polish Officers in the Katyn Forest Near Smolensk, Russia. Part 3 (Chicago, ILL.) March 13 and 14, 1952. (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1952), p. 461.

The Voice of America (VOA) Director Amanda Bennett, who was appointed during the Obama administration and served in that position from 2016 to 2020 and was later appointed by President Biden to become in 2021 the current CEO of the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM), wrote in an opinion article in The Washington Post that “The radio broadcast that eventually became Voice of America was created to give people trapped behind Nazi lines accurate, truthful news about the war, in contrast with Nazi propaganda.” Her assertion was not entirely false but also not entirely true. What the VOA Director may not know or forgot to mention is that U.S. government propaganda during World War II, including Voice of America broadcasts, was, in addition to providing a lot of factual information about the course of the war and Nazi atrocities, also severely tainted with many half-truths and deliberate lies designed to protect from domestic and foreign criticism a critical U.S. military ally–Soviet Russia and its communist dictator Josef Stalin. One of those lies in early Voice of America broadcasts was about the Gulag prison labor camps and its millions of victims. If one listened to these VOA broadcasts from 1942 to 1945 and even for a few years more, such camps did not exist, and no one was leaving Soviet Russia during the war because they might have been afraid of Stalin and communism.

A Brief Stay In A Former Detention Camp For Japanese Americans

To block media access to prevent the publication of negative stories about life in the Soviet Union, American officials in charge of Polish refugee orphans who had arrived in the United States in 1943 after fleeing Russia put them in a former detention facility for Japanese Americans at the Santa Anita U.S. Army training camp near Los Angeles. After a few days of quarantine, they promptly dispatched the entire group to Mexico, where they were placed in a refugee camp under an earlier agreement between Polish Prime Minister General Władysław Sikorski and the Mexican government. Sikorski had traveled to Mexico in December 1942 to meet with Mexican President Manuel Avila Camacho. The Polish-Mexican agreement called for assisting several thousand Polish refugees from Russia, who were then held in temporary camps in Iran. Out of 37,272 civilians who were Polish citizens evacuated from Russia to Iran in 1942, 13,948 were children. 1,434, most of them children, eventually arrived in Mexico. To get to Mexico, the Polish children had to be transported from India on a U.S. Navy ship to a U.S. port. Their transport and support were negotiated between the Polish government in exile, represented in Washington by Ambassador Jan Ciechanowski, and the Roosevelt administration.

To block media access to prevent the publication of negative stories about life in the Soviet Union, American officials in charge of Polish refugee orphans who had arrived in the United States in 1943 after fleeing Russia put them in a former detention facility for Japanese Americans at the Santa Anita U.S. Army training camp near Los Angeles. After a few days of quarantine, they promptly dispatched the entire group to Mexico, where they were placed in a refugee camp under an earlier agreement between Polish Prime Minister General Władysław Sikorski and the Mexican government. Sikorski had traveled to Mexico in December 1942 to meet with Mexican President Manuel Avila Camacho. The Polish-Mexican agreement called for assisting several thousand Polish refugees from Russia, who were then held in temporary camps in Iran. Out of 37,272 civilians who were Polish citizens evacuated from Russia to Iran in 1942, 13,948 were children. 1,434, most of them children, eventually arrived in Mexico. To get to Mexico, the Polish children had to be transported from India on a U.S. Navy ship to a U.S. port. Their transport and support were negotiated between the Polish government in exile, represented in Washington by Ambassador Jan Ciechanowski, and the Roosevelt administration.

Many of the children were orphans. Some were accompanied only by their mothers. Their fathers had been either executed or died as prisoners in the Soviet Union. The children and their Polish adult caregivers, also former prisoners in Russia, had been told by Polish and American government representatives that they were going to Mexico with a brief stopover on the west coast of the United States, but their reception after their arrival in southern California was much different from what they had expected. As one of the surviving children said years later, finding themselves being put on U.S. Army trucks, transported to a detention center, and kept behind a barbed wire fence guarded by American soldiers with rifles compounded the trauma of their recent imprisonment in Soviet Russia. They barely managed to leave the country that had arrested their parents and deported them from their homes in eastern Poland. They were hoping to taste complete freedom in America, which they idealized. They found that they were not allowed to walk free and visit or interact with the people in the country of their dreams, except for some camp personnel and a few representatives of relief organizations. Most did not see the United States again until a few years after the war.

Before they arrived in a port in California on the U.S. Navy ship Hermitage, they endured unbelievable suffering. They completed a long journey from Russia to Iran, India, and finally to Los Angeles. Compared to the horrific conditions they had endured in Russia, these Polish children were treated with compassion and kindness by U.S. Army officers, soldiers, doctors, nurses, and other Americans with whom they came in contact. They were not completely abandoned and without help. The Polish Army, under the command of General Anders, which later fought against German armies alongside American and British forces, took care of them in Russia after their release from the Gulag and evacuated them to Iran. The Anders Army and civilian representatives of the Polish government in exile in London, the British government, and the U.S. government arranged for humanitarian aid and medical care in Iran for the children, their mothers, and other Polish refugees. The U.S. government paid for and organized their ocean voyage from India. It should also be added for the sake of balance that it was much more than most World War II refugees, including the Jews fleeing from the Holocaust, could hope for from the Roosevelt administration. President Roosevelt refused the request from the Polish government in exile to resettle the children in the United States, but he did approve a $3 million U.S. assistance program to bring them to Mexico.

Transported In Sealed Trains To Mexico

After a few days spent in the detention center in California, the children were transported on a comfortable but locked train to Mexico. They remained under military guard as they rode through the southern United States. U.S. soldiers locked all train doors and windows and had orders not to allow anyone to talk with the passengers. What American officials feared most was that the story of the Soviet Gulag labor camps would leak out and become widely known through media reports about what really happened to these children and their parents in Russia. Secondly, officials feared publicity might encourage others in Europe to seek refugee status in the United States. There was concern that some of the children or their Polish caregivers might try to escape and remain illegally in the United States. No such escape attempts were reported.

The Roosevelt administration rejected requests for American adoptions, which would have been the most apparent and most humane solution to the problem of parentless Polish children. Officials would not allow these very young refugees from the Gulag to be placed with Polish American families. The U.S. government wanted to keep them isolated and to get them out of the country as soon as possible in case their continued stay and any media publicity could result in turning American public opinion against Soviet dictator Josef Stalin. Only when the American train they were on had reached the U.S.-Mexican border in Texas the rifle-carrying U.S. guards disappeared. One of the children said later that they had finally experienced complete freedom at that moment. Their lack of knowledge of Spanish prevented them from talking with the many Mexicans who came out to greet them, but they were finally free to speak to anyone they wanted. The warm welcome they had received in Mexico made a lasting impression. Those among them who are still alive continue to speak of their deep love and affection for Mexico. They continue to express gratitude to the Mexican people for allowing them to stay in their country when they needed help and a safe place to live.

Victims Of Hitler Or Stalin?

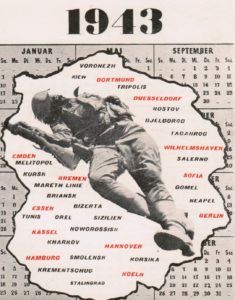

Since the news of the children’s earlier arrival in the United States could not be completely hidden from the Polish American media, to confuse other Americans as well as foreign audiences listening to shortwave radio broadcasts of the Voice of America, propagandists in the FDR administration tried to portray these young refugees as fleeing from Nazi-occupied Poland rather than from the Soviet Union. Pro-Soviet officials in charge of U.S. propaganda did not want American and foreign radio listeners to learn about any communist atrocities. They feared that such negative publicity could undermine public support for the U.S.-Russia anti-Hitler alliance or might even force Stalin to seek a truce and another pact with Hitler. While these fears were unfounded (a bipartisan congressional committee referred to them as “a strange psychosis that military necessity required the sacrifice of loyal allies and our own principles in order to keep Russia from making a separate peace with the Nazis.”), Hitler and Stalin were, in fact, war allies from August 1939 until June 1941. In 1939, Soviet Russia invaded and occupied the eastern part of Poland, annexed the Baltic States, and attacked Finland. In 1940, the Red Army occupied Romanian Bessarabia. The Soviets removed from their homes, imprisoned, and forcefully deported in cattle train cars under the most inhuman conditions hundreds of thousands of Poles and people of many other nationalities: Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Belorussians, Ukrainians, Tatars, Jews, and many others. Many were arrested and executed. Others died during the deportations or later from harsh treatment, hard forced labor, starvation, and illness. Only very few survivors managed to leave the Soviet Union during the war. They needed to be resettled in safe areas along with many other refugees who were fleeing countries occupied by Nazi Germany in east-central, southern and western Europe. Most Polish children who had escaped from Soviet Russia ended up in the British colonies in Africa, India, and New Zealand, which accepted 700 children.

Soviet propaganda at times presented Polish refugees from Russia as being saved by Stalin, while American propaganda portrayed them as fleeing from the Nazis. Many refugees were fleeing the Nazi rule, but these Polish children were not chased out of their homes and imprisoned by the Nazis. They lived in the part of Poland occupied in 1939 by the Red Army, and they were prisoners in the Soviet Union. Polish American newspapers and the better-informed mainstream press tried to make these distinctions clear, while Soviet and U.S. government propagandists did everything possible to mislead and confuse Americans and foreign audiences about the nature of the Stalinist regime, presenting it as pro-democratic and progressive.

During World War II, both refugee groups, those from Russia and those from Nazi-occupied or controlled Europe, received some limited help from American diplomats and employees of American relief organizations who tried to find nations willing to accept them, but even those U.S. efforts, especially those undertaken by the State Department, were usually kept secret. Most Jews fleeing the Nazis and facing certain death if they were to be caught by the Germans or their allies were not granted political asylum in the United States due to the many nearly impossible-to-meet legal conditions strictly enforced by U.S. consular officials.

Polish refugee children at the Colonia Santa Rosa camp in Guanajuato, Mexico, stage an Eastern pageant – photo from the U.S. National Archives.

Edward R. Murrow And VOA Followers Of Walter Duranty

At the time, the rest of America knew very little about these Polish children, not only because of the official news blackout about their trip and misleading information being put out by the U.S. government but also because propagandists in the Roosevelt administration played the role of illegal censors targeting Polish-American media which had the most direct interest in their story. Despite some censorship and shutting down of a few radio programs due to illegal demands from U.S. officials, most Polish American radio stations and newspapers managed to report accurately about the arrival of Polish refugee children and their brief stay in the United States. Mainstream American media did not pay much attention to the Polish refugees from Russia, but some American journalists tried to expose the danger of Soviet communism and the unnecessary appeasement of Stalin. CBS wartime correspondent Edward R. Murrow was among them. He reported from London in 1943 that the Soviets were responsible for the Katyn Forest massacre of 15,000 Polish military officers while the Voice of America was at the same time aggressively spreading the Kremlin’s propaganda lie that the Germans had carried out the mass murder. Murrow also reported on Stalin’s betrayal of the 1944 Warsaw Uprising, while the Voice of America, in line with what the Soviets wanted, mostly ignored the non-communist Poles and their underground army fighting the Germans in Poland. Soviet propaganda called these anti-Nazi Poles “fascists” and “reactionaries.”

Effective propaganda relies less on outright lies than accurate information skillfully manipulated and presented without critical material facts and context. Such propaganda succeeds when journalists repeat propaganda messages or acquiesce with silence and censorship in response to pressure from the government engaging in disinformation. To avoid offending “Uncle Joe,” as President Roosevelt sometimes playfully referred to Stalin, American officials had decided not to broadcast in Russian during the Second World War. They seemed convinced that Soviet propaganda, which many Soviet sympathizers among them and VOA broadcasters inserted into American broadcasts, was good enough for the Russians or, in any case, should not be challenged. Russian was the only major world language missing from the VOA program lineup until 1947. Caving into Soviet pressure and also out of their pro-Soviet sympathies, strongly Left-leaning progressives, socialists, and a few communists working as U.S. government propagandists misled Americans and the world about refugees fleeing communist oppression in Russia. The voices of the former Gulag prisoners were ignored and silenced because of what was perceived as military necessity and because of the ideological bias of the Voice of America personnel. The Polish American press tried to report on the story, but it was insufficient to get national attention. The Roosevelt administration resorted to lies, deception, and censorship to keep the refugee story from being told.

These historical facts have now been forgotten. In my view, the then-VOA Director and the current U.S. Agency for Global Media CEO Amanda Bennett inaccurately suggested in her Washington Post op-ed that Edward R. Murrow “helped to create VOA.” This outstanding American reporter had no direct role in the creation of VOA. Voice of America’s early officials and broadcasters were definitely not followers of his model of truthful reporting on anything related to the Soviet Union and communism. They were followers of the type of pro-Soviet propaganda promoted in the United States by Anglo-American New York Times correspondent in Soviet Russia Walter Duranty, who received the 1932 Pulitzer Prize for outstanding reporting from the Soviet Union. Amanda Bennett was a member of the 2002-2003 Pulitzer Prize Board that in 2003 refused to revoke Duranty’s Pulitzer Prize. Duranty was a denier of Bolshevik-caused widespread famine in the USSR with millions of victims, particularly in Ukraine. It would be more accurate to mention Walter Duranty as someone whose example inspired early VOA reporting on the Soviet Union, which was diametrically different from later Cold War-era VOA reporting. VOA changed and started to expose and counter Soviet propaganda, but only after the Truman administration carried out long-delayed reforms in the early 1950s.

A Group Lost In History

Although there are significant differences in their respective status and the treatment today’s migrants in Mexico and World War II refugees received from the American government and media, the previously untold plight of Polish orphans fleeing from communist Russia showed the corruptive nature of Soviet and American government propaganda, primarily when the two worked in tandem during World War II. Propaganda strategies were, in fact, secretly coordinated between Washington and Moscow by Robert E. Sherwood, one of the “founding fathers” of what is known today as the Voice of America (VOA). He was a Hollywood playwright, President Roosevelt’s speechwriter, and the head of the Overseas Division in the wartime U.S. Office of War Information (OWI), which placed him in charge of VOA radio broadcasts.

Voice of America broadcasters almost certainly did not tell the story of Czesław (Chester) Sawko “whose grim memory included carrying his little brother’s body to a makeshift morgue at a [Russian] railway station,” or the story another child refugee, Stanisława Synowiec (Stella Tobis), who “saw her mother for the last time when her train in Russia left without warning after her mother had got off in search of food.” She never saw her mother again. Czesław Sawko and Stanisława Synowiec both made it to Hacienda Santa Rosa. Only after the war were they able to resettle in the United States. Eventually, they learned that while the Roosevelt administration did not want them in the United States, it was not how most Americans would have reacted had they known all the facts and not been lied to by U.S. government propagandists.

A Polish lawyer, Joanna Matias, whose father Bogdan Matias (Wierciński) was the first Polish child born during the war in the Santa Rosa camp, met with some of the former refugees who now live in Mexico and the United States. Her grandfather, his health destroyed by imprisonment in Russia, died in Mexico shortly after the war at the age of 26. Ms. Matias tells their stories in her Santa Rosa blog and writes about her trip to Mexico to find her grandfather’s grave.

While the majority of the Polish inhabitants of the Santa Rosa colony emigrated after the war to the United States thanks to the Displaced Persons Act of 1948, strongly supported by President Truman and his administration, they still remember the incredible warmth and hospitality shown to them by the Mexican people and the Mexican government. They also received help from individual Americans, including workers of Polish American and Catholic relief organizations, but the difference in their initial reception in the United States and Mexico was for many of them striking. Piotr Piwowarczyk, a journalist and film producer who lives in Mexico, described the brief journey of Polish refugee children through California during World War II as “surreal.”

“Having gained their freedom, the refugees arrived in America, a place that in their minds was freedom itself. But to their utter amazement, as they got off the ship, they were immediately put on military trucks and taken to a nearby internment camp holding Japanese Americans. [By that time Japanese Americans were most likely no longer there having been been placed earlier in permanent internment camps.] The Poles noted with misgivings that their own section of ‘Santa Anita’ was enclosed by barbed wire. They felt like prisoners again. Better conditions than in the Soviet Union but certainly not the America of their dreams. After four days, they were loaded onto military trucks again and taken to a train under military guard that remained posted at every door throughout their journey of some seven hours. The windows remained sealed, and no one was permitted to leave their coaches.”

Even the Polish government in exile, eager to mend its relations with Moscow, discouraged the refugees from speaking about their experiences in Russia. There was pressure on them from all sides to remain silent. One of the children refugees, Teresa Sokołowska, said many years later that they were condemned to be forgotten.

“Nobody spoke or wrote about our fate. After the end of the Second World War, we were a group lost in history.”

Only much later, some of the stories of the Polish children prisoners in the Soviet Union started to appear in print and on the Internet. In 2015, Piwowarczyk and director Sławomir Gruenberg released a documentary about the Santa Rosa settlement, Joanna Matias’ meetings with some of its former inhabitants, and her search in Mexico for her grandfather’s grave. The film is also partly a tribute to Mexico and its people for giving Polish refugees a welcoming haven after the horrors of imprisonment in Russia and a rather disheartening initial encounter with America.

Soviet And U.S. Propaganda Lies

U.S. government propagandists and Voice of America broadcasters were responding, often willingly and enthusiastically, to the relentless pressure from the Soviet government to present only a communist-tainted version of the news. Airing foreign propaganda lies was not something most Americans would have approved of had they known about it, but essential facts were being withheld from them during the war. They were lied to by their government in the interest of keeping Russia as an ally to achieve a quick victory over Nazi Germany and Japan.

It would be unfair to say that all of America as a nation colluded with Russia or approved of selling Eastern Europe down the river to Stalin at wartime summit conferences in Tehran and Yalta; President Roosevelt and certain officials in his administration did that, and then even some of them, including FDR, did it out of idealism and ignorance rather than any ill-will toward Poland and other East European nations. They themselves were also uncritical recipients of Soviet lies and victims of Soviet pressure and disinformation.

Because of propaganda and censorship, most Americans had no clear idea what was going on behind the scenes in the U.S.-Russia relationship. Even the Polish American community was deceived by false promises from President Roosevelt and his propagandists. Most Polish Americans voted for FDR in U.S. elections. After the end of the war, it took several years before the Voice of America was reformed, thanks to intense pressure from Congress, and started broadcasting accurate and more detailed news to counter Soviet propaganda in the later years of the Cold War. By then, however, the story of Polish children brought out of the Soviet Union and shipped to Mexico was too old and so well censored earlier that it failed to get attention from most American media. It faded into obscurity.

Polish refugee children relaxing in Santa Rosa, Mexico. Photo from the U.S. National Archives.

In making historical comparisons about immigration, it should be pointed out that today’s migrants in Mexico are not Jews fleeing the World War II Holocaust in Europe or Poles escaping death from executions and forced labor in Soviet Russia. Except for Cuba and Venezuela, there are no totalitarian regimes in Latin America, so such comparisons would not be appropriate or helpful. What is critically needed today is a look at how foreign and domestic propaganda was and is still being used to confuse and deceive American public opinion out of ideological or partisan motives about specific important domestic and international issues, or in some cases, serves the interests of foreign powers and nations, such as Russia, China, Iran, or terrorist organizations like Hamas, through skillful manipulation of news and social media. Some of today’s Voice of America journalists working for the U.S. Agency for Global Media post images on their personal social media pages calling for the violent destruction of the Jewish state in Israel, while their VOA managers and editors instruct them not to refer to Hamas as “terrorists” but to call them “militants” or “fighters.” It is a much larger problem affecting the mainstream U.S. media and universities. In an op-ed in The Hill, I quoted my former VOA Polish Service colleague, Jewish-American writer Henryk Grynberg: “The president of a leading American university cannot apologize for her lack of basic human values” toward Jews. Grynberg, a much-admired writer, poet, and chronicler of Jewish history in Poland, who is also a child survivor of the Holocaust, said that the real culprit is “the culture that brought her up so high.” That culture must purge itself of antisemitism before apologies can be made, Grynberg added.

As journalists, he and I are both sorry that our former employer, the U.S. Agency for Global Media, also does not want to refer to Hamas’ murderers and war criminals as “terrorists,” preferring instead to call them “fighters” so as to remain “neutral.” But can those who murder defenseless women and children — people who cannot fight back — be called “fighters?” Doesn’t the word “fighter” inherently imply an actual fight between combatants, as opposed to the systematic rape and massacre of civilians?

World War II U.S. government propaganda, while not nearly as crude as Soviet propaganda, was designed to protect Stalin and his aggressive aims, ultimately at the expense of long-term American interests and fundamental American values. Polish refugee children who had been Stalin’s prisoners became an annoying reminder for the Left-leaning Roosevelt administration officials in the Office of War Information and the Voice of America that Stalin had been once Hitler’s ally. They wanted to portray the Soviet Union as making tremendous sacrifices in fighting German Nazis and other Fascists to establish freedom and democracy in Eastern Europe. Quite a few of them, especially radical Leftists, believed this to be true. Soviet soldiers were indeed making great sacrifices fighting the Nazis, but they were also used to bring East Central Europe into Stalin’s Soviet empire. There was no excuse for the incredibly naive belief in the non-existent Soviet support for democracy and freedom. Still, the radical American Left wanted to see democratic socialism prevail throughout Europe and expected Stalin and local communists to help.

A few of the most Left-leaning and dedicated lower-ranking World War II Voice of America broadcasters ended up working for the Soviet-imposed communist regimes in Eastern Europe after the war. Later, this became an embarrassment for moderate supporters of FDR’s policies and future Democratic administrations and for the United States as a free and democratic nation that could not protect itself and the U.S. government from such individuals. Partly as a result of U.S. concessions made to Stalin at Teheran and Yalta, millions of East Europeans lost their freedom for several decades. Whether this could have been completely avoided with a firmer approach will remain unknown because, with or without Yalta, the Soviet Red Army had achieved control over East Central Europe and would not leave without a fight. Eventually, America changed its mind about Stalin and the Soviet Union, but the American embarrassment over the Yalta Agreement contributed in part to the story of the young Polish victims of Stalin’s crimes being forgotten. Talking about it publicly would not show the United States in the best light as Americans, including by then the Voice of America, were containing Soviet aggression, countering Soviet propaganda during the Cold War, and trying to reverse the mistakes of Yalta.

A Polish American Newspaper Takes On A U.S. Propaganda Agency

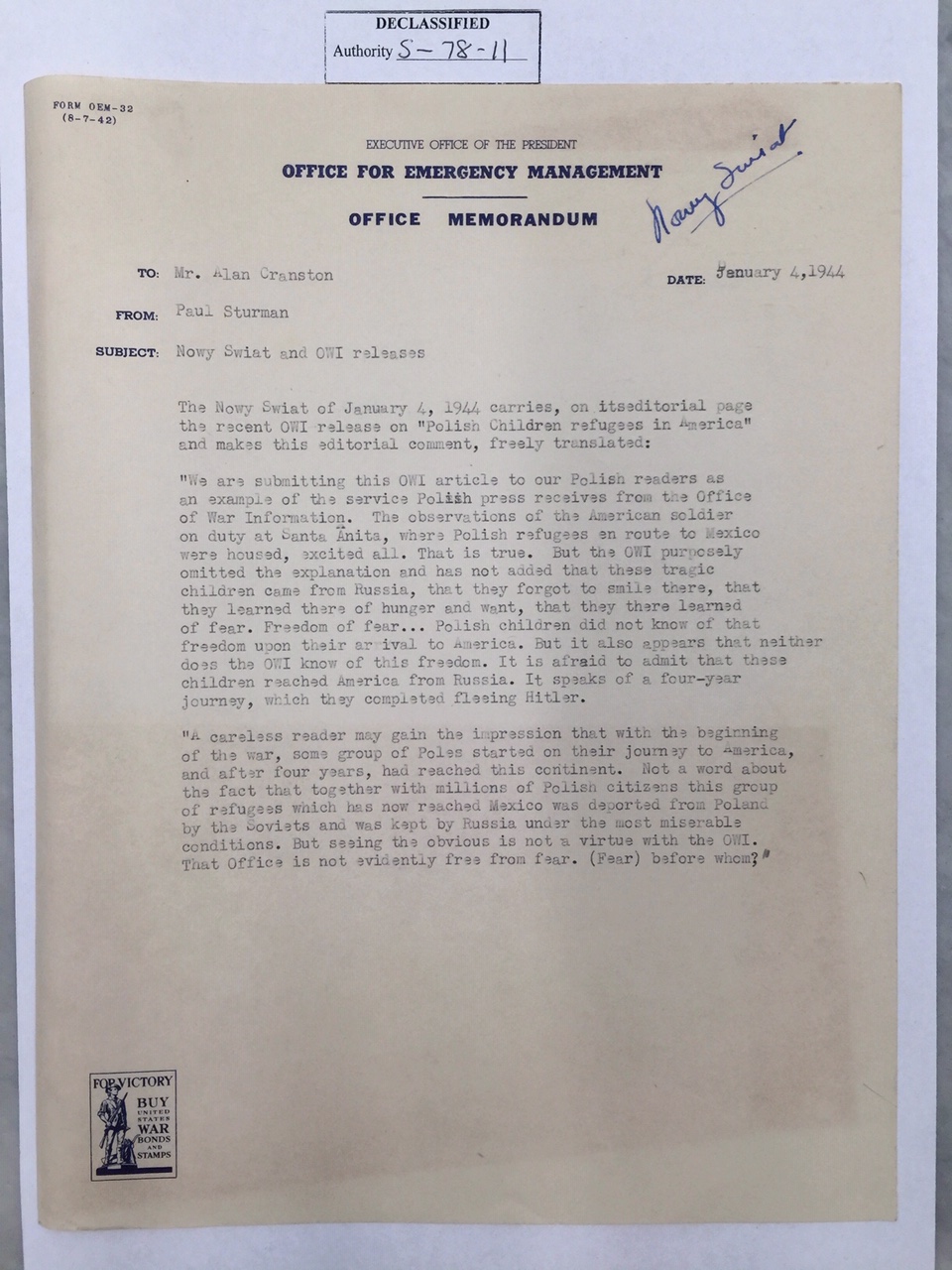

A U.S. government World War II document I discovered a few years ago in the National Archives offers a rare glimpse into how the wartime propaganda agency, the Office of War Information, which was in charge of both domestic and foreign U.S. government propaganda, including Voice of America radio broadcasts to Germany, Japan, Poland, and other countries, tried to deceive American and foreign audiences about the Polish refugee children from Russia to protect Stalin’s reputation and America’s alliance with the Soviet Union. By then, Russia was admittedly the most important U.S. military ally against Nazi Germany, but only after Hitler broke his previous pact with Stalin and attacked the Soviet Union in 1941. The children who came from the eastern part of Poland, occupied by the Red Army in 1939, were not victims of Hitler’s Fascism; they were victims of Stalin’s totalitarian Communism. They never saw any German occupiers. As the Polish American newspaper Nowy Świat pointed out in January 1944, they were arrested with their parents by the Soviets and sent to the Soviet Gulag.

“The OWI purposely omitted the explanation and has not added that these tragic children came from Russia, that they forgot to smile there, that they learned there of hunger and want, that they there learned of fear.”

“A careless reader may gain the impression that with the beginning of the war, some group of Poles started on their journey to America, and after four years, had reached this continent. Not a word about the fact that together with millions of Polish citizens this group of refugees which has now reached Mexico was deported from Poland by the Soviets and was kept by Russia under the most miserable conditions. But seeing the obvious is not a virtue with the OWI. That Office is not evidently free from fear. (Fear) before whom?”

In its January 4, 1944 editorial, Nowy Świat (“New World”) correctly assessed the U.S. government’s propaganda. The U.S. government press release included a kernel of truth but was otherwise designed to deceive.

The first transport of 706 Polish refugees, including 166 children, aboard the USS Hermitage, reached the San Pedro naval dock near Los Angeles on June 25, 1943. The women and children under 14 were placed in the Griffith Park Internment Camp in Burbank, and the men in the Alien Camp in Tuna Canyon. The second group of 726 Polish refugees, including 408 children, mostly orphans, arrived on the USS Hermitage in the fall of 1943 and was placed in the Santa Anita former detention camp for Japanese Americans. It was the second group that was mentioned in the misleading press release from the Office of War Information.

Polish refugee women working in the fields of Hacienda Santa Rosa, which, according to a description provided by National Archives researcher Robin Waldman, included a “39-room ranch house, a flour mill, ten wheat storage warehouses, a chapel, and other buildings, as well as several acres for growing crops. By October 1943, almost 1,500 Poles were sheltered at Colonia Santa Rosa.” Photo from the U.S. National Archives.

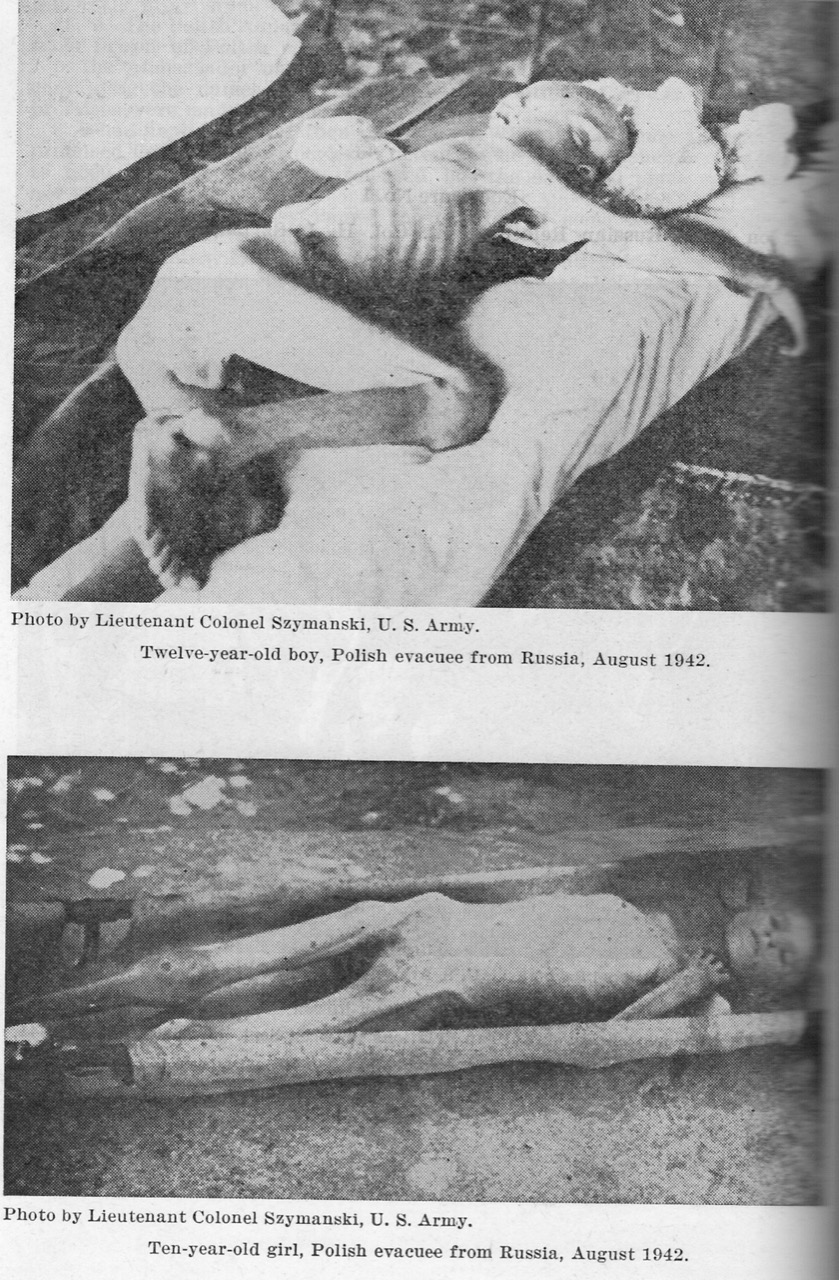

OWI only published pictures of relatively healthy-looking Polish refugee children while deceptively presenting them to Americans as fleeing from the Nazis. Graphic photos taken earlier by a U.S. Army photographer showing starving and dying Polish children who had been rescued from Russia and brought to Iran with the Polish Army of General Władysław Anders were classified by the U.S. government as secret and prevented from being made public during the war and even for several years after the war. It took an intervention by members of the U.S. Congress to get some of the photos and documents declassified in the early 1950s.

The first photo was taken in Tehran by an OWI photographer. This and similar OWI photos show no apparent signs of malnutrition or illness. The other three photos, taken by a U.S. Army intelligence officer, show Polish children arriving in Iran from Russia who look no different than inmates of Nazi concentration camps. The U.S. government immediately classified these photos as secret and did not make them public until 1952.

Parrino, Nick, photographer. Teheran, Iran. A Polish woman and her grandchildren are shown in an American Red Cross evacuation camp as they await evacuation to new homes. Tehran, Iran, 1943. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017854329/.

A six-year-old boy, a Polish evacuee from Russia, in August 1942. Photo by Lieutenant Colonel Szymanski, U.S. Army. The Katyn Forest Massacre. Hearings Before the Select Committee to Conduct An Investigation of the Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Foreign Massacre. Eighty-Second Congress, Second Session on Investigation of the Murder of Thousands of Polish Officers in the Katyn Forest Near Smolensk, Russia. Part 3 (Chicago, ILL.) March 13 and 14, 1952. (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1952), p. 459.

A twelve-year-old boy, a Polish evacuee from Russia, August 1942. A ten-year-old girl, a Polish evacuee from Russia, in August 1942. Photos by Lieutenant Colonel Szymanski U.S. Army. The Katyn Forest Massacre. Hearings Before the Select Committee to Conduct An Investigation of the Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Foreign Massacre. Eighty-Second Congress, Second Session on Investigation of the Murder of Thousands of Polish Officers in the Katyn Forest Near Smolensk, Russia. Part 3 (Chicago, ILL.) March 13 and 14, 1952. (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1952), p. 460.

The Katyn Massacre

OWI photos and publications distributed to newspapers in the United States and abroad were not the only form of misleading government propaganda. In perhaps the most outstanding example of fake news of the 20th century, the Office of War Information and the Voice of America spread false Soviet claims about the Katyn Forest massacre of thousands of Polish military officers who had been taken by the Soviets as prisoners of war in 1939 and secretly executed by the NKVD secret police on the orders of Stalin and the Soviet Politburo in Katyn and in other locations in 1940. The Soviets tried to blame the massacre on the Germans. Moscow was immediately assisted in this disinformation effort by Voice of America propagandists, some of whom knew or should have known the truth. In April 1943, even the U.S. State Department warned officials in charge of VOA that they were on shaky grounds in promoting the Soviet version of the Katyn atrocity.

Earlier, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt ignored a secret request from Sikorski’s wife, Helena Sikorska, to use her influence with Stalin in locating and saving the lives of thousands of missing Polish military officers. Sikorska attached several letters from their wives begging for help finding their husbands. When those letters were written in 1942, the men were already dead, murdered on Stalin’s orders two years earlier. Eleanor Roosevelt forwarded Sikorska’s letter to the State Department without taking any action.

With their parents dead (fathers of some of them were executed in Katyn), many Polish orphans who had managed to leave the Soviet Union for Iran after the Polish Government in exile in London reached a brief agreement with Stalin in 1941 had to be taken care of and resettled. The Iranians warmly received them, but even with British and American help, such large numbers of refugees could not be cared for in Iran. Most of them had to be repatriated to other countries. In 1942, the Roosevelt administration refused a secret request from Prime Minister Sikorski addressed to President Roosevelt to bring 10,000 Polish children from Iran to the U.S., where Polish-American families would have been more than willing to take them under their care. The U.S. government suggested Mexico as an alternative, no doubt in part to prevent facts about the Katyn massacre from becoming known in America.

A Warm Welcome In Africa and India

The British government arranged for some Polish children to be taken to India and Africa, where – just as in Mexico – they were welcomed and well-treated by the local authorities and people. They would have been well-treated by Americans had the Roosevelt administration allowed them to stay in the United States in 1943. Many eventually came to the United States from Africa, India, and Great Britain only after the war. Some settled in Canada, New Zealand, and Australia. A Canadian filmmaker, writer, and director, Jonathan Kołodziej Durand, has produced an award-winning documentary about the Polish children who found temporary refuge in Africa, “Memory Is Our Homeland.” His grandmother was one of the children sent to Africa.

Digvijaysinhji Ranjitsinhj, the Maharaja Jam Sahib of Nawanagar in India, accepted about 1,000 Polish children and constructed a camp for them near his palace. A video documentary, “A Little Poland in India,” offers, in addition to the story of Polish children who found refuge in India, an excellent historical background of what happened between 1939 and the end of World War II.

Censorship Of U.S. Media

During the war, pro-Soviet U.S. government propagandists in the Office of War Information and the Voice of America might have succeeded in completely deceiving the American public about Polish refugees from Russia if it were not for some U.S. media reports, many of them originated by Polish-American newspapers and radio stations. These small independent ethnic media outlets told the truth about communist atrocities in Soviet Russia and Stalin’s plans to impose Soviet rule over Eastern Europe. Some members of Congress, mostly Republicans but also a few Democrats, placed transcripts of some of these news reports in the Congressional Record. World War II Voice of America radio broadcasts and OWI propagandists, on the other hand, presented Stalin as a defender of liberty and democracy against Fascism. The truth about communist crimes was suppressed within the U.S. government. Some of FDR’s most enthusiastic pro-Soviet propagandists simply refused to believe that Stalin could be a mass murderer. In violation of American laws, they declared a secret war on the anti-communist Polish-American newspapers and radio stations.

During the war, OWI officials were especially angered by the Polish-American newspaper Nowy Świat‘s reporting on the Soviet responsibility for the Katyn Massacre even before the mass graves of Polish military officers were discovered in 1943. In 1942, OWI officials tried to get the U.S. Department of Justice to close down the paper. In secret memos, government bureaucrats described Nowy Świat editors as anti-Soviet and pro-Fascist. The Young Communist League in the United States, which was controlled from Moscow, referred to the Polish Government in exile as “the imperialist Polish government dominated by pro-Fascist elements” even though Poland was occupied by Nazi Germany and the armed forces of the exiled Polish government were fighting the Germans alongside American and British armies.

The OWI’s secret attempt to shut down or effectively censor Nowy Świat was ultimately unsuccessful, but one of OWI’s key bureaucrats, Alan Cranston, succeeded in silencing a few Polish-American radio programs critical of Stalin and the Soviet Union. He later had a successful political career in the Democratic Party, becoming a U.S. Senator from California.

During the war, Cranston oversaw OWI’s domestic propaganda division. OWI’s overseas division, including the Voice of America, also had several strongly pro-communist managers. One of them was the man declared later to be the first VOA director, theatre producer, and Hollywood actor, John Houseman. His hiring of communists to prepare U.S. government radio programs was too much even for some of the influential, progressive members of the Roosevelt administration, one of them Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, who was FDR’s close friend and advisor. The State Department and the War Department put pressure on the White House to get John Houseman and other radically pro-Soviet propagandists removed from the Office of War Information. He was quietly forced to resign in 1943, but pro-Soviet VOA propaganda broadcasts continued for the duration of the war under other pro-Soviet officials and broadcasters. Even toward the end of the war and afterward, some tried to support the consolidation of communist rule in East Central Europe with American propaganda in Voice of America broadcasts. In 1952, a bipartisan committee of the U.S. House of Representatives condemned Alan Cranston’s wartime censorship activities as illegal and concluded that the Voice of America maintained its pro-Soviet bias for several years after the war.

After The War

Very few Americans knew then or know now that Mexico, from where today’s immigrants often try to enter the United States legally and illegally, became, during World War II, a welcoming haven for a large group of Polish refugee children who had lost their parents in Russia. They remained in Mexico for several years and did not try to re-enter the United States illegally or leave their camp, Colonia Santa Rosa, in the Mexican state of Guanajuato. Leaving the camp would have been a violation of the 1942 Polish-Mexican agreement about their resettlement, and its violators were punished. Mexican court records show that at least one Polish woman was sentenced to 30 days in jail for sleeping outside the camp. Polish refugees were also prohibited from seeking any work that might compete with Mexican labor. In many ways, however, their situation before they arrived in Mexico was quite different from that of today’s migrants from Latin America.

After the war’s end, the Mexican government offered the Polish refugees a chance to apply for political asylum in Mexico, but most of them, despite the shock of their initial treatment after they arrived in California in 1943, preferred to resettle in the United States with its large Polish-American community and better economic opportunities. Only very few chose to return to Poland, by then ruled by a Soviet-imposed communist regime. Most World War II Polish refugees waited in Mexico and other countries for several years before getting their U.S. immigration visas. Also, by then, more Americans had become aware of President Roosevelt’s sellout of Poland and other East European countries to Stalin at his wartime conferences with Stalin and Churchill in Teheran and Yalta. America began to rectify its mistakes.

However, one of the most tragic mistakes that could not be rectified was frequent denials of political asylum and immigration visas to helpless Jewish men, women, and children trying to flee Europe. Some of those whose requests for political asylum in the United States had been refused were later murdered in German concentration camps.

DECLASSIFIED

Authority S – 78 – 11

EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT

OFFICE FOR EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT

OFFICE MEMORANDUM

TO: Mr. Alan Cranston

DATE: January 4, 1944

FROM: Paul Sturman

SUBJECT: Nowy Swiat and OWI releases

The Nowy Swiat of January 4, 1944 carries, on its editorial page the recent OWI release on “Polish Children refugees in America” and makes this editorial comment, freely translated:

“We are submitting this OWI article to our Polish readers as an example of the service Polish press receives from the Office of War Information. The observations of the American soldier on duty at Santa Anita, where Polish refugees en route to Mexico were housed, excited all. That is true. But the OWI purposely omitted the explanation and has not added that these tragic children came from Russia, that they forgot to smile there, that they learned there of hunger and want, that they there learned of fear. Freedom of fear… Polish children did not know of that freedom upon their arrival to America. But it also appears that neither

does the OWI know of this freedom. It is afraid to admit that these children reached America from Russia. It speaks of a four-year journey, which they completed fleeing Hitler.“A careless reader may gain the impression that with the beginning of the war, some group of Poles started on their journey to America, and after four years, had reached this continent. Not a word about the fact that together with millions of Polish citizens this group of refugees which has now reached Mexico was deported from Poland by the Soviets and was kept by Russia under the most miserable conditions. But seeing the obvious is not a virtue with the OWI. That Office is not evidently free from fear. (Fear) before whom?”

Correcting Mistakes

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin met at Yalta in February 1945 to discuss their joint occupation of Germany and plans for postwar Europe, including allowing Stalin, without the knowledge or agreement of the Polish government in exile, to incorporate into the Soviet Union the eastern part of Poland. Behind them stand, from the left, Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, Fleet Admiral Ernest King, Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, General of the Army George Marshall, Major General Laurence S. Kuter, General Aleksei Antonov, Vice Admiral Stepan Kucherov, and Admiral of the Fleet Nikolay Kuznetsov. February 1945. (Army) US government photographer. The exact Date Shot is Unknown. NARA FILE #: 111-SC-260486. WAR & CONFLICT BOOK #: 750″

It took nearly a decade to move the VOA from being a propaganda outlet for the Soviet Union to become an essential instrument in countering communist propaganda during the Cold War. The U.S. government also created Radio Free Europe, which had a larger audience and influence in Poland for most of the Cold War than the poorly managed and underfunded VOA. RFE publicized the Katyn massacre story much more effectively than VOA, but the story of the Polish refugee children from Russia never received wider media attention in the U.S. The silencing of their voices continued for many decades.

Officials in charge of the Voice of America never acknowledged the role of many of its early leaders and broadcasters as eager pro-Soviet propagandists who covered up Stalin’s crimes and helped him consolidate communist rule over Eastern Europe. Most of the Polish refugees, including Polish soldiers who were prisoners in Soviet Russia and later fought against the Nazis with American and British forces in North Africa and Western Europe, remained in Great Britain. Many eventually resettled in the U.S. They had to wait several years for their U.S. immigration visas, and some had to pay for their travel and resettlement.

In the later years of the Cold War, the U.S. led the Western effort to reverse the effects of Yalta. Radio Free Europe and Voice of America broadcasts played an important role in that effort. The Polish refugee children sent to Mexico in 1943 who later came to the United States had successful careers and lives. They became U.S. citizens and patriotic Americans but never lost their love for Mexico and Poland. Some were fortunate enough to see Poland becoming independent from Soviet domination, free, and democratic in the last decade of the 20th century.

Soviet treatment of human beings was genocidal, and Soviet propaganda was designed to hide this fact using every available means of disinformation, manipulation, and deception. In many ways, Polish women – mothers, children, and grandmothers – suffered more than the Polish men in Soviet captivity. Many lost their sons and husbands and were put to work as slave laborers under the most inhuman conditions. Most of them, however, adjusted well to life in freedom in the West after the war. They were sustained by their patriotism and, for many, by their religious faith. They found support in their families and communities, but they will never forget what happened to them in Russia. They still mourn their lost family members and friends.

U.S. government officials in the Roosevelt administration were, for the most part, extremely naive and unable to see through Soviet propaganda and to comprehend and acknowledge Stalin’s atrocities. Their idealism turned some of them into unwitting agents of the Soviet government, especially in the U.S. wartime federal agency producing Voice of America radio broadcasts.

American government propaganda was, by comparison with Soviet propaganda, much more moderate and driven by far less nefarious motives, but ultimately, it was effective in deceiving American public opinion that Stalin was a progressive leader who believed in democracy in Eastern Europe and that the Soviet Union would remain America’s friend and ally after the war. Key U.S. officials seemed convinced that such assumptions were valid, and they ignored and suppressed evidence that undermined their views and convictions. A few officials in the Roosevelt administration took secret and illegal actions to silence some of the U.S. media criticism of the appeasement of Stalin.

Not all Americans, however, were deceived. There were many warnings from some members of Congress and parts of the American media. America’s ability to eventually see through Soviet propaganda and admit the mistakes of its government resulted in the West’s eventual victory over Soviet communism.

But sadly, in the last few years, some Voice of America programs have again begun to show ignorance of the lessons of history. In one report in 2017, VOA presented Angela Davis, an American Communist, Lenin Peace Prize winner, and ardent supporter of the Soviet Union, as a fighter for workers and women’s rights. Also in 2017, VOA posted a monologue video presenting Angela Davis as “representing the powerful forces of change [in] Women’s March.” Neither VOA report identified her as a Communist whom Russian dissident writer, former Gulag prisoner, and Nobel Prize laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn condemned in 1975 for refusing to help political dissidents in communist prisons. (The Voice of America censored Solzhenitsyn for several years during the period of detente with the Soviet Union in the 1970s.) VOA broadcasts to Iran were recently exposed in an independent study for including pro-Iranian regime propaganda and ignoring American voices critical of the regime. There are also reports that VOA’s senior management, despite strong opposition from its journalists, has caved into pressure from the communist government in China and is punishing VOA Chinese broadcasters who complain that they were victims of censorship.

Keeping in mind how the early Voice of America propagandists lied to protect Stalin, if we don’t remember history, if we forget the genuine victims of genocide and try to find excuses for Hamas terrorists, if we accept foreign and partisan propaganda as truth, the United States may again make serious mistakes, and it will later regret.