April 1943 – State Department Warns White House of Soviet Influence at Voice of America

May 4, 2018

Analysis by Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

In 2018, the online Cold War Radio Museum presented for the first time to a broader online audience a secret 1943 memorandum sent to the Roosevelt White House by the U.S. State Department. The communication raised suspicions about John Houseman, considered to be the first director of the Voice of America (VOA) as being a communist sympathizer and too pro-Soviet to be trusted in a high-level sensitive government position in charge of U.S. radio broadcasts overseas. 1 The memorandum informed the White House that the State Department refused him permission to travel abroad as a U.S. government representative.

In 2018, the online Cold War Radio Museum presented for the first time to a broader online audience a secret 1943 memorandum sent to the Roosevelt White House by the U.S. State Department. The communication raised suspicions about John Houseman, considered to be the first director of the Voice of America (VOA) as being a communist sympathizer and too pro-Soviet to be trusted in a high-level sensitive government position in charge of U.S. radio broadcasts overseas. 1 The memorandum informed the White House that the State Department refused him permission to travel abroad as a U.S. government representative.

At the height of World War II, the U.S. diplomatic service and the U.S. military authorities had secretly declared the chief producer of VOA broadcasts to be untrustworthy because of his excessive pro-Soviet and communist sympathies. They came to this conclusion even though the Soviet Union was regarded by President Roosevelt as America’s indispensable military ally against Nazi Germany and hopefully later in the war also against Japan.

There were no direct accusations in the memo or details of any ongoing subversive activities. The most serious charge was that Houseman was hiring communists to fill Voice of America positions. This accusation against Houseman was true. Whether he did it on instructions from the Communist Party USA, or whether he had received and followed such instructions while working for the Voice of America, is not mentioned in the memorandum. How he did it was not specified. Real Soviet agents would routinely use their influence with individuals such as Houseman to place real agents or individuals highly sympathetic to the Soviet Union in U.S. government jobs. Even if the target of their activity was not a Communist Party member subject to party discipline, they knew how to manipulate those who participated in the Kremlin-controlled communist “front” organizations. Within a few weeks, John Houseman resigned from his position as the head of the Radio Program Bureau in the Overseas Branch of the Office of War Information, the current day Voice of America. 2

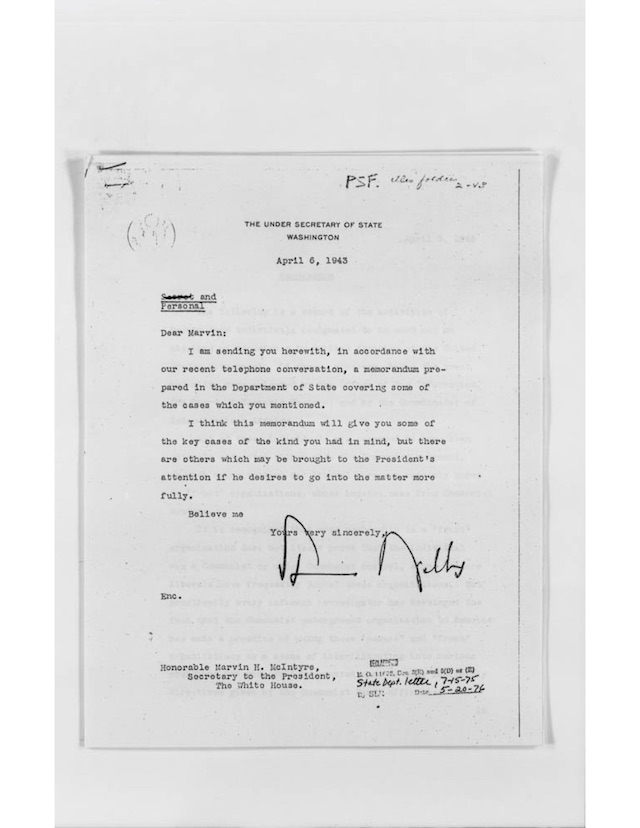

The memorandum about Soviet and communist influence within the wartime Voice of America included a cover memo written by Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles. He was a distinguished career diplomat, a major foreign policy advisor to President Roosevelt, and his friend. Welles’ letter was sent to the White House on April 6, 1943. The attached memorandum with the addendum listing names of individuals who had been denied U.S. passports for government travel abroad was dated April 5, 1943. The documents were declassified in the mid-1970s and have been accessible online for some time from the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum Website 3 and the National Archives 4. It appears, however, that they have never been widely disclosed and analyzed before now. They were presented for the first time with a historical analysis on the Cold War Radio Museum website.

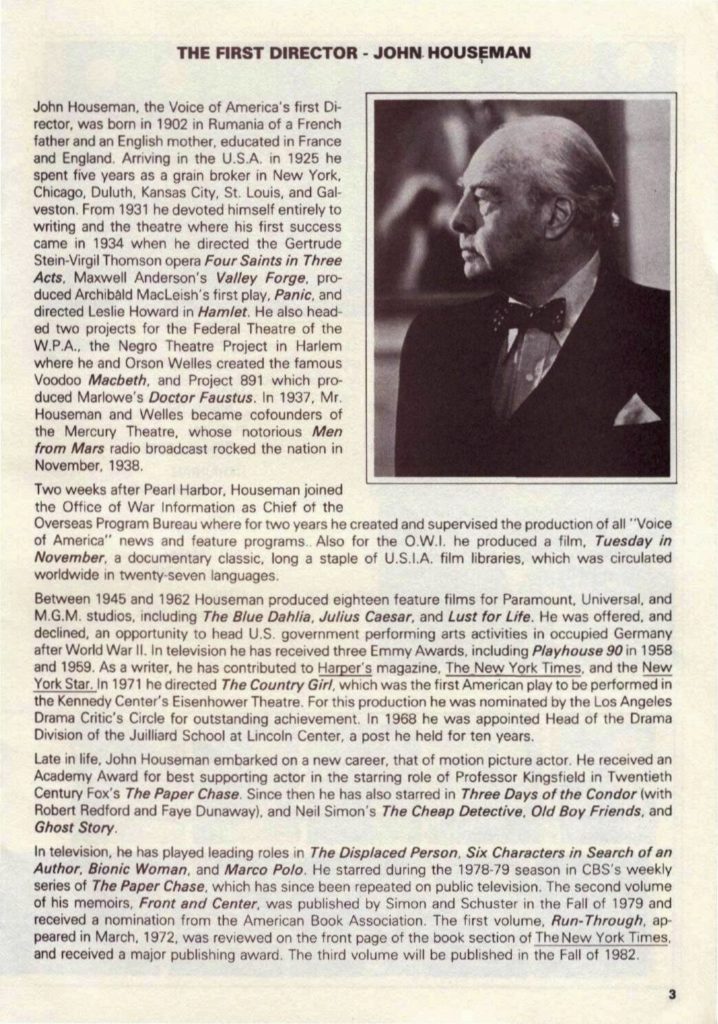

John Houseman (born Jacques Haussmann in Romania to a British mother and a French father; September 22, 1902 – October 31, 1988) was a theater producer, radio producer, and Hollywood actor now known mostly for his Oscar-winning role as Professor Charles W. Kingsfield in the 1973 film The Paper Chase and his commercials for the brokerage firm Smith Barney about making money the old-fashioned way. He emigrated to the United States in 1925 and worked as a grain broker before starting his theater, radio, and movie career and collaboration with theater and film director Orson Welles (no relation to Sumner Welles). They reportedly caused some amount of panic in much of the United States with their 1938 Mercury Theatre on the Air production of H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds which mixed genuinely sounding but fake evening radio news bulletins with dramatic descriptions of an alien invasion.

A 1982 Voice of America one-page biography mentioned Houseman’s collaboration with Orson Welles in producing the movie classic Citizen Kane. It also noted “the notorious Men from Mars [sic] radio broadcast [which] rocked [sic] the nation in November 1938” (it actually aired on Halloween, October 30, 1938 over the Columbia Broadcasting System radio network) but did not explain the broadcast’s significance as a pioneering experiment in fake news, in this case at least for purely entertainment purposes.

In late 1941 or very early 1942, John Houseman, whose legal name then was Jacques Haussmann, was officially hired by his friend, American playwright and Roosevelt’s speechwriter Robert E. Sherwood. Recruited, based on Sherwood’s and Nelson Poynter’s recommendations, he began to work for the Coordinator of Information, the U.S. government office in charge of spying, and propaganda. Through President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9182 issued June 13, 1942, the office of the Coordinator of Information was turned into the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), while the radio unit where Houseman worked became the Office of War Information (OWI). 5

Houseman’s hiring was not hidden from the State Department, which is where, according to his autobiography, he was interviewed by both Robert Sherwood and William J. (“Wild Bill”) Donovan, the wartime head of the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). It appears that the State Department and the Office of the Coordinator of Information, the future OSS and CIA, did not have initially any objections to Houseman being hired.

The later promoters of the John Houseman myth as a supporter of accurate news reporting and a symbol of VOA’s journalistic objectivity would be shocked to know that he was hired by the head of the U.S. intelligence agency in a meeting held in one of the State Department buildings, which may have also had the office of the Coordinator of Information. It is not clear whether any career U.S. diplomats participated in the meeting, but the chief of the U.S. spying agency did. If one is to believe how John Houseman described the meeting, the spy agency chief asked him to create the future Voice of America for propaganda warfare.

Such were the beginnings of the Voice of America. Its initial mission was to launch propaganda operations against Nazi Germany, Japan, and other fascist Axis regimes. What the U.S. intelligence service and the State Department may not have anticipated was the inclusion of Soviet propaganda in VOA broadcasts under Houseman and his immediate successors.

“A week later I was flying East on a Government priority. In a telegram from Washington, Robert Sherwood had asked me to meet him in the State Department Building, where he introduced me to a tough, white-haired charmer named William Donovan who asked me if I would undertake the organization and programming of the Overseas Radio operation for the Coordinator of Information.” 6

Houseman’s description of the meeting also has a reference to “U.S. wartime propaganda” and not a word about news reporting. “We were starting from scratch, Bob [Sherwood] explained, with no equipment or personnel and no clear notion of what form U.S. wartime propaganda should take.” 7

In a later edition of his autobiography (1989), titled Unfinished Business, Houseman confirms that his first official U.S. government employer was in the office which later became the OSS and still later the CIA. At the time of Houseman’s hiring to run the radio division, U.S. spying and propaganda were in the same office of the Coordinator of Information. Houseman noted that even after the separation of “covert operations” from propaganda operations, Robert Sherwood was still in charge of “psychological warfare.” The emphasis was on propaganda and psychological warfare rather than news reporting.

“Early in June [1943], after months of infighting, the long-awaited ‘reorganization’ was announced. It separated Donovan’s ‘covert operations’ (which became the OSS and later the CIA) from Overseas Information and Propaganda. This left Sherwood free to move with his plans for psychological warfare.” 8

Houseman wrote that the Foreign Information Service (which included the future VOA) had “the humane and civilized quality” given to it by Robert Sherwood who, as Houseman pointed out quoting an unnamed historian, was waging “a people’s war, a gallant crusade against the forces of reaction that could make the world a better place to live in.” 9

Stalin and the Soviet Union were to Sherwood, Houseman and their team some of the most important allies in that struggle. Whoever opposed them was branded as an enemy and a right-wing reactionary. According to one of Sherwood’s “propaganda directives” to the Voice of America staff, dated May 1, 1943, the Poles who refused to accept as true Soviet propaganda on the mass murder of thousands of their prisoners of war in Russia were guilty of “consciously or unconsciously cooperating with Hitler.” 10

The VOA team of communists and left-wing radicals labeled those who opposed communism and Soviet domination as fascists, even though the same anti-communist Poles accused by Sherwood of “cooperating with Hitler” were the first to fight the Nazis. They continued to fight them in occupied Poland, Africa, and Western Europe. Members of the underground state and army in Poland would have been tortured and killed if they had fallen into the hands of the German Gestapo. Soldiers and officers of the Polish Army in the West, under the command of the Polish government in exile in London, were fighting the Germans alongside American and British troops in North Africa and in Italy.

In Sherwood’s and VOA’s version of pro-Stalin propaganda and disinformation, the Soviet message of anti-communists as supporters of fascism was slightly less brutal than in Radio Moscow broadcasts, but it was nevertheless clear. These U.S. officials swore later they had no idea that Stalin could be capable of serving them lies. Most of them should not have been running the Voice of America on behalf of the U.S. government and the American people, but they did.

Hardly anyone in the United States or abroad remembers today that John Houseman was at one time in charge of such propaganda in the VOA radio division. Practically, no one knows that he got the U.S. government job from the Roosevelt administration without having U.S. citizenship or any prior experience in news reporting and radio journalism. The fact that he had frequent contacts with the Communist Party in the United States before his federal employment has never been widely revealed. He was probably hired without any initial security clearance and himself hired communists only to attract suspicions later.

John Houseman was declared by some, perhaps not entirely accurately, the first VOA director during the period from early January 1942 through July 1943. The overall content of the first VOA programs, which Houseman produced, was determined by his superiors, although he played a significant role together with them in shaping the broadcasts and in hiring radio personnel before he was forced to resign over various programming scandals. His strong advocacy for Soviet and communist causes put him at odds even with the pro-Soviet FDR White House.

Throughout this period, Roosevelt most likely was not even aware of Houseman and his work, but the president had selected and knew well some of his superiors. The ones with close links to FDR, Robert E. Sherwood and Office of War Information director Elmer Davis, did not lose their OWI jobs. They were helping FDR also on the domestic news and information front. The lines between foreign and domestic propaganda were blurred. OWI’s U.S. government employees did both domestic and foreign news reporting and other media outreach, but they generally avoided domestic propaganda of purely partisan nature. They promoted FDR and his policies, but they did not directly attack the Republican Party and its politicians, as some VOA executives, editors and reporters do today in violation of the VOA Charter, the bipartisan U.S. law passed in 1976 to prevent such abuses.

At the time, Houseman’s tenure as director of what was later known as the Voice of America did not attract much media attention due to his rather secondary role at the Office of War Information, but the word of his activities at VOA and the communists he had recruited must have gotten eventually to U.S. government security officials, including the Army Intelligence, and the State Department. They acted to deny him a U.S. passport in what was an effort to get him fired from his VOA position.

The Voice of America’s most important World War II first-line journalist was a communist and a pro-Soviet propagandist. He was the VOA chief news writer in 1942-1943, but he is now almost completely erased from VOA’ history except for his own memoir, a few old interviews, a biography by Gerald Sorin, and previously classified U.S. government documents. Howard Fast, a best-selling American author, member of the Communist Party USA from 1943 to 1956, and a recipient of the 1953 $25,000 Stalin Peace Prize, wrote some of the first Voice of America news programs. Having given him the award which would have been worth over 260,000.00 in today’s (2022) dollars, the Soviets had to have been rather pleased with his past journalistic work for VOA and his later reporting for the Communist Party newspaper, the Daily Worker. Fast worked for John Houseman and saw him as his main patron and friend.

The newly rediscovered Sumner Welles memorandum represents yet another proof that foreign radio propaganda activities of VOA’s early left-wing radicals working under John Houseman, Joseph F. Barnes, and Robert Sherwood eventually became intolerable even for the progressive and strongly pro-Soviet Franklin D. Roosevelt administration. It was an early, albeit then still secret indication that officials close to FDR, who were not opposed to his pro-Russia policy, became concerned about the threat of Soviet interference within the U.S. government, specifically at the Office of War Information and its division producing radio programs for overseas audiences.

In light of many subsequent but now largely forgotten scandals in the early history of the Voice of America and the ultimate tragic consequences of U.S. wartime policy toward Soviet Russia—millions of East Europeans losing their freedom for several decades, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and other Cold War crises and setbacks, which perhaps could have been avoided—these initial concerns about some of the key individuals in charge of U.S. government propaganda radio broadcasting trying to strengthen Russia’s international position, especially toward the end of World War II, were fully justified.

According to one contemporary listener to VOA wartime broadcasts from New York and Washington, a left-leaning Polish Peasant Party politician, Stanisław Mikołajczyk, who even joined briefly the communist government in Warsaw after the war before fleeing to the West to save his life:

“[Voice of America wartime radio broadcasts] might well have emanated from Moscow itself.” 11

Another Pole, the Polish government in exile ambassador in Washington, Jan Ciechanowski, had similar observations:

“Of all the United States Government agencies, the Office of War Information [where Voice of America was placed], under its new director, Mr. Elmer Davis, had very definitely adopted a line of unqualified praise of Soviet Russia and appeared to support its shrewd and increasingly aggressive propaganda in the United States. The OWI broadcasts to European countries had become characteristic of this trend.” 12

“I protested repeatedly against the pro-Soviet character of such propaganda. I explained to those responsible for it in the OWI that the Polish nation, suffering untold oppression from Hitler’s hordes, was thirsting for plain news about America and especially about her war effort, her postwar plans, and her moral leadership, that Soviet propaganda was being continuously broadcast anyway to Poland directly from Moscow, and there seemed no reason additionally to broadcast it from the United States.” 13

“When I finally appealed to the Secretary of State and to divisional heads of the State Department, protesting against the character of the OWI broadcasts to Poland, I was told that the State Department was aware of these facts but could not control this agency, which boasted that it received its directives straight from the White House.” 14

One of the ironies of history is that the Voice of America, which in its early phase helped Stalin to achieve Russia’s domination over East-Central Europe, in later years contributed greatly to helping free the so-called “Captive Nations” from Russia’s indirect but firm imperial rule through local communist dictatorships.

A tendency of all propagandists is to present a simple, one-sided view of history which emphasizes one set of facts while ignoring others. The history of the Voice of America has been as varied and as complex as the history of the Cold War. There may be a few defining events in VOA’s past that are not controversial and have a simple explanation. But a major tilt toward Soviet Russia, America’s temporary military ally yet a long term strategic foe, was undeniable in the early VOA broadcasts. This has been an unacknowledged since the 1950s. However, VOA’s later role in the Cold War must be seen as tremendously positive in support of freedom and human rights, although still marred by occasional reversals and not always as effective as it could have been because of its placement within the U.S. federal government bureaucracy. At the same time, the lack of strong government oversight over the activities of VOA’s government employees turned out to be even more dangerous for taxpayer-funded journalism and national security.

In assessing the first years of its existence, it should be noted at the outset that the Voice of America alone would not have been able to cause or prevent the Soviet takeover of Eastern Europe. Statesmen such as President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and much larger geopolitical and military forces were decisive in this case.

Disinterested experts and even some former propagandists agree that foreign propaganda by itself cannot win or lose a major military conflict, not even the Cold War in the second half of the last century. That conflict was won through a combination of political, military and economic factors reinforced by American and other Western radio broadcasts and various other forms of public diplomacy. VOA’s wartime broadcasts, however, played a small part in helping to make the communist victory in East Central Europe somewhat easier through unwitting assistance in the much larger Soviet military, security, intelligence and disinformation operations which used agents of influence as valuable assets.

VOA helped the Soviet Union in a propaganda campaign by giving encouragement to the pro-Moscow factions and attacking, ignoring, censoring or banning those who opposed the communists and were seen by VOA’s leftist broadcasters as enemies of communism, peace and progress. Soviet propaganda labeled these mostly democratic political forces as reactionary and fascist, just as the Kremlin’s propaganda machine does today against its enemies—and, in a victory of chaos over reason, even gets some media in the West to do the same. The stark divide between fascism and progress with nothing in between is taken straight out of the communist propaganda handbook.

Considering its revealing content about Soviet subversion tactics, as described by a mid-20th century second-ranking official at the Department of State and author of the historic Welles Declaration, a further analysis of the 1943 Welles memo about John Houseman and other pro-Soviet Americans and foreigners who were associated with U.S. overseas broadcasting during World War II could be an interesting addition to the ongoing debate and controversy over Russia’s recent attempts to use propaganda and disinformation for justifying aggression against other states and the Kremlin’s attempts to influence U.S. policy and American elections in covert and illegal ways.

The Welles Declaration, 15 an important U.S. diplomatic statement issued by Sumner Welles in 1940 when he was Acting Secretary of State, reaffirmed America’s non-recognition of the Soviet occupation of the Baltic States. They were occupied by Soviet Russia in fulfillment of the secret terms of the 1939 Hitler-Stalin Pact. Also known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, it led to the start of World War II with the joint German-Soviet invasion of Poland in September 1939.

John Houseman’s autobiography, first published in 1972, is revealing for ignoring such major historical events, which cast a shadow on communism and the Soviet Union. while describing in some detail, but definitely not fully or with complete honesty, his collaboration as a theater producer with the Communist Party. It also shows that he believed the Kremlin’s opponents, especially among the East European émigrés, to be all reactionaries and enemies of social justice. It was one of his many naive or false beliefs.

Soviet and communist subversion remains a sensitive topic in the United States even after the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections and the sudden and dramatic change in attitudes toward Russia among many on the Left and some on the Right. There is now little historical memory of the previous, far-reaching and successful Russian efforts to subvert the U.S. government with the help of U.S. public officials as their ideological allies, if not in most cases actual paid agents of influence.

This lack of broader knowledge of the history of Soviet and Russian covert political subversion in the United States, as opposed to open public diplomacy and open media influence, is partly due to many such accusations having been discredited as unfounded during the anti-communist witch hunt led by Senator Joseph McCarthy in the early 1950s against the political Left. It’s also because, unlike today, such accusations had usually been directed in the past by Republicans against Democrats and Democratic administrations. They were deemed suspect by mainstream media, which refused to analyze them, and thus condemned them to being largely forgotten.

After McCarthy, and until very recently, raising accusations of collusion with Russia were often seen on the Left and most of the moderate Right as paranoid and un-American. McCarthy, however, was not wrong in every instance. Soviet propaganda combined with intelligence activities in the United States was particularly strong in the 1930s and the 1940s, and dangerously subversive in its influence.

Soviet spies and agents stole U.S. atomic secrets. Soviet propaganda and disinformation campaigns helped to shape the Roosevelt administration’s foreign policy and got the President to betray many of America’s wartime allies and to accept in conferences with Stalin at Tehran and Yalta his plans for achieving domination over East Central Europe. At the same time, Soviet agents were infiltrating the U.S. government to steal secret information and spread propaganda to influence policy decisions. Some of them found their way into the Office of War Information, although the OWI was not the most important target of Soviet espionage activities.

The Soviet subversion of the U.S. government had started long before Senator McCarthy launched his anti-communist crusade. While many of McCarthy’s later claims were simply completely false and almost always malicious, most of the accusations leveled secretly by the State Department in 1943 against Houseman and some of the other officials in charge of the wartime Voice of America broadcasts turned out to be at least partially true regarding their propaganda in support of Soviet ideological and foreign policy objectives.

There was, of course, a major and legitimate need to show support for an ally fighting Nazi Germany and a considerable convergence of military interests between the two countries during the war. At the same time, Soviet and communist political goals were opposed by many members of Congress and the vast majority of Americans. In some cases, they were opposed even by President Roosevelt and his top diplomatic and military policymakers, including Sumner Welles and Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces in Europe and later U.S. President, General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The accusations in the 1943 memo against the persons in charge of Voice of America broadcasts were not partisan in nature or designed to be leaked to the media to damage domestic political opponents. They were advanced secretly by key liberal and progressive foreign policy advisors to President Roosevelt against other administration officials. Nearly all of these officials on both sides were Democrats.

Historian Holly Cowan Shulman, who in her book, The Voice of America: Propaganda and Democracy, 1941-1945, was not unsympathetic to the radical left-wing worldview of the founders of the Voice of America, noted that in their senior federal government positions they sometimes deliberately opposed some of President Roosevelt’s foreign policies when they believed them to be “anti-liberal” and “anti-democratic.” One could add that they also saw them as harmful to the Soviet Union. 16

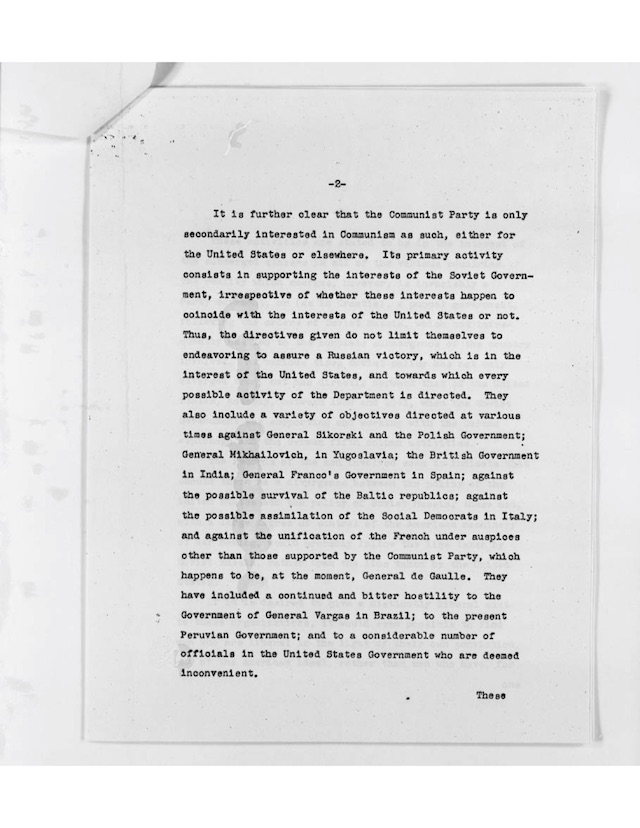

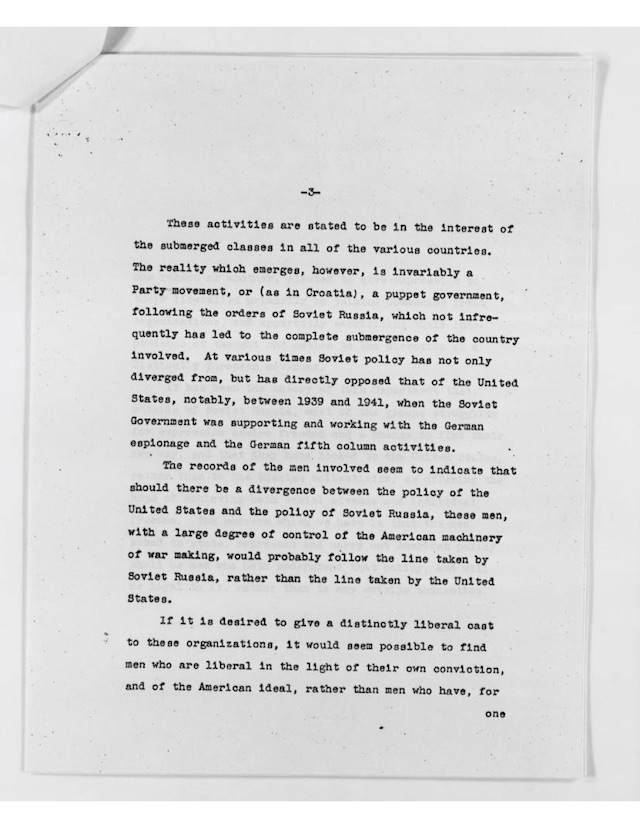

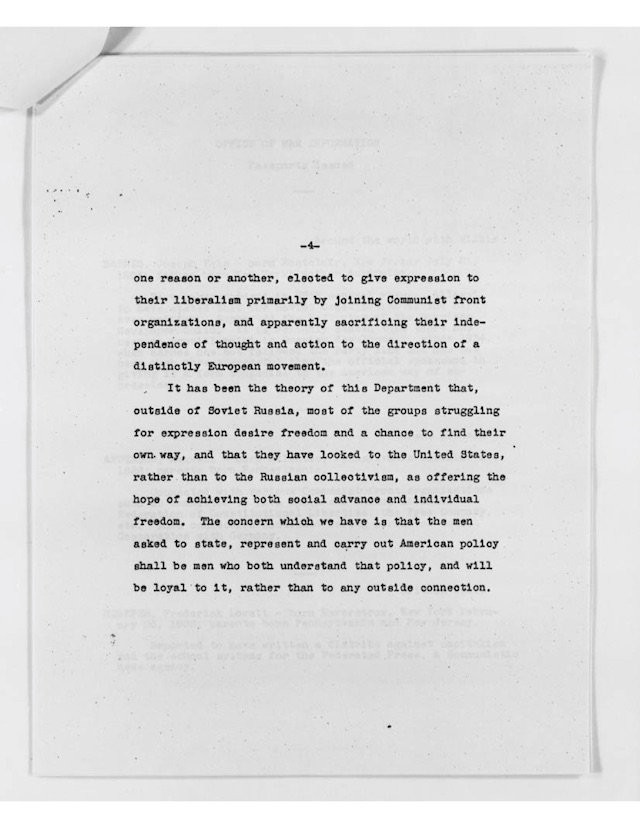

Stalin, U.S. and foreign communists also opposed some of President Roosevelt’s policies, although most of his policies and decisions were in favor of Russia at the expense of small nations of East Central Europe. As the Welles 1943 memorandum pointed out, the assumptions on the part of U.S. officials in charge of VOA radio broadcasts about American-born and foreign-born communists represented a dangerous and distorted interpretation of liberalism and ran counter to American traditions of liberal thought. Had they been only private U.S. citizens, American communists would have had fully protected constitutional rights to public dissent even during wartime, even if public acceptance of such rights was more limited than it is now. Such non-violent public dissent would not have been a sign of disloyalty to the United States. But as federal officials hired by the FDR administration, they were disloyal to the President and to the government of the United States.

Officials in charge of the Office of War Information and VOA propagandists were putting the lives of American soldiers at risk and helping Russia to take away the liberty of millions of people—all in the name of defending peace, liberty, and democracy. Their only excuse later could have been that they did not know Stalin had nefarious plans, and that FDR’s overall policy toward Russia would have produced the same end result for the VOA audience in Eastern Europe, regardless of what VOA broadcast or did not broadcast.

Had these officials and broadcasters been working for a purely private U.S. media organization, they would have also had the right to engage in journalistic advocacy subject to internal editorial policies, but the Voice of America then and now is a U.S. government entity, fully funded by all American taxpayers, with special rules and much enhanced responsibilities, some of them of legal nature. Honest and idealistic individuals with good intentions can be very dangerous in government positions if they are deceived by their lack of knowledge and lack of experience while being blinded by an ideology and manipulated by a foreign power.

The 1943 State Department memo included an addendum about Houseman and a few other Office of War Information senior-level employees who were denied U.S. passports for their proposed official trips abroad because of suspicions of their communist and Soviet sympathies or for being suspected of joining the Communist Party.

In reading the State Department memo and its addenda, it is important to note that the “Voice of America” name was not yet then commonly used to refer to OWI’s Overseas Branch and its radio broadcasts. It became the official name a few years later. It is also important to note that such terms as “propaganda” and “psychological warfare,” when used to describe U.S. or British wartime radio broadcasting, did not have nearly the same negative connotations in America as they do today.

Another important point to remember is that even private U.S. citizens, who now have the right to almost unrestricted private travel abroad, were not given such rights under the U.S. laws and regulations in effect through most of the 20th century. John Houseman’s request for a U.S. passport for official, not private travel, was totally within the discretion of the U.S. government then, as it would be today.

Likewise important to know is that Houseman, despite being given later by some the title of the first Voice of America director, was not in fact the principle individual responsible for the political content of VOA programs. This, however, made little difference because he fully shared his superiors’ enthusiasm for Russia, Stalin, and communism. Those most responsible for programming policy and for running overseas broadcasts and the radio organization in New York were equally far left-leaning Robert E. Sherwood and Joseph F. Barnes.

Their boss, Washington-based OWI director Elmer Davis, only slightly less left-leaning than Sherwood, Barnes and Houseman, at times recorded his own radio broadcasts, in which he repeated Soviet disinformation propaganda lies.

Davis claimed later that he did it on his own initiative without being prompted by the White House. Whether he was telling the truth cannot be determined with certainty, but it seems doubtful that he never received any orders from President Roosevelt or the White House staff.

For one key broadcast of the war, on the Katyn Forest Massacre, the State Department advised him not to promote the Soviet propaganda lie. The OWI and its Radio Bureau, i.e. the Voice of America, ignored the advice. Later, Elmer Davis could not recall receiving it. He and others all categorically denied after the war that they knew at the time that the information provided by the Soviet Union and broadcast by them or by the Voice of America at their insistence was in any way false. Even years later, they continued to attack their critics, who turned out to be right.

The trip to North Africa for which the U.S. State Department refused to issue a U.S. passport to John Houseman, by then a newly naturalized U.S. citizen, was proposed by his friend and patron Robert E. Sherwood, described by some as one of the founding fathers of the Voice of America. It was Sherwood who had hired Houseman to be the producer of the first VOA broadcasts by putting him in charge of the Radio Bureau of the Office of War Information in New York.

In March 1943, Sherwood also helped Houseman obtain his U.S. citizenship in an expedited manner, having hired him in 1942 for his high-level government job while Houseman was still a non-citizen. Before his employment at VOA, he had lived and worked in the United States for 17 years–seven of them, he said later, as an undocumented immigrant.

Being born in Romania—although his parents were not Romanian but French and British—he could have been mistaken by some for an enemy alien in the fearful atmosphere following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Houseman implied later that he was definitely classified as an enemy alien, but his family background was French and British.

Houseman’s claim of being an enemy alien seems somewhat suspect. He described himself in his autobiography as “Romanian by birth.” A more accurate description would have been “born in Romania to non-Romanian parents.” Neither his mother nor his father was Romanian. His father was a French-Jewish businessman working in Romania. John Houseman also called himself “French by inheritance” and “English by upbringing and naturalization,” an indication that he did have British citizenship while living and working without a proper visa in the United States. 17

While Sherwood was able to arrange for Houseman to become a U.S. citizen without going through the normal process, he was subsequently unable to persuade the State Department and the Army Intelligence (G-2) to allow Houseman to travel abroad on official U.S. government business. Sherwood’s subsequent appeal to the White House on behalf of the VOA director to get the diplomatic and military ban on Houseman’s official travel lifted proved unsuccessful.

Houseman may have been ignoring or covering up the real reasons for his shortened career as a U.S. government employee that had nothing to do with him being born in Romania or being an immigrant. Before and after him, many U.S.-born citizens were fired from their U.S. government jobs, suspected, sometimes falsely, of being suspected members of the Communist Party. It could not be established whether the U.S. government officially considered him as an enemy alien, and he was vague whether he even had acquired Romanian citizenship at any time. He did admit, however, that he was selected for a sensitive government position without having a U.S. citizenship. That claim was true since he did not become naturalized until March 1943 but was already in charge of the Voice of America since the prior year.

“As I received my civil service appointment in the name of Jacques Haussmann (whose naturalization papers, filed in 1936 had not yet come through) no one–least of all myself–seemed to question the propriety of placing the Voice of America under the direction of an enemy alien of Romanian birth who, as such, was expressly forbidden by the Department of Justice to go near a shortwave radio set.” 18

The problem the Roosevelt administration had later with John Houseman was not his immigration status or citizenship. He was initially hired by the same administration, although the U.S. citizenship should have been the minimal requirement for his position. The real problem as it developed later appeared to have been his links with the Communist Party, the hiring of communists, and the Moscow-line content of VOA broadcasts.

His boss and close friend, Joseph Barnes, who was a U.S. born citizen, was fired for the same reasons Houseman was forced to resign from his government position. The type of citizenship or national origin did not seem to matter much in Houseman’s case, but it may have increased suspicions against him, as it did against other recent immigrants from Europe.

In Houseman’s case, the authorities would have had fewer reasons to be suspicious than about some other immigrants. He was white, successful and rich. He spoke perfect English, was fully integrated into American life, had powerful friends in Hollywood and New York, and did not fit the profile of a typical enemy spy. The focus was on his contacts with the Communist Party and accusations that he was hiring communists. If his previous immigration status played any role in the investigation into his past cannot be determined from the available documents. It may have had a minor impact.

The State Department informed the White House that Houseman was among several senior OWI employees, both U.S. born and naturalized citizens, whose applications for official U.S. passports were denied. Under Secretary of State Welles wrote that other such cases may be brought to the President’s attention “if he desires to go into the matter more fully.” There was no known follow-up from the White House in Houseman’s case.

It is not clear from the memorandum whether the State Department and the Army Intelligence would have also objected to Houseman traveling abroad as a private citizen during the war. They most likely would have, since at that time, even being suspected of membership or having links to a subversive organization without any definite proof or due process was seen as sufficient grounds for denying U.S. citizens the right to travel abroad.

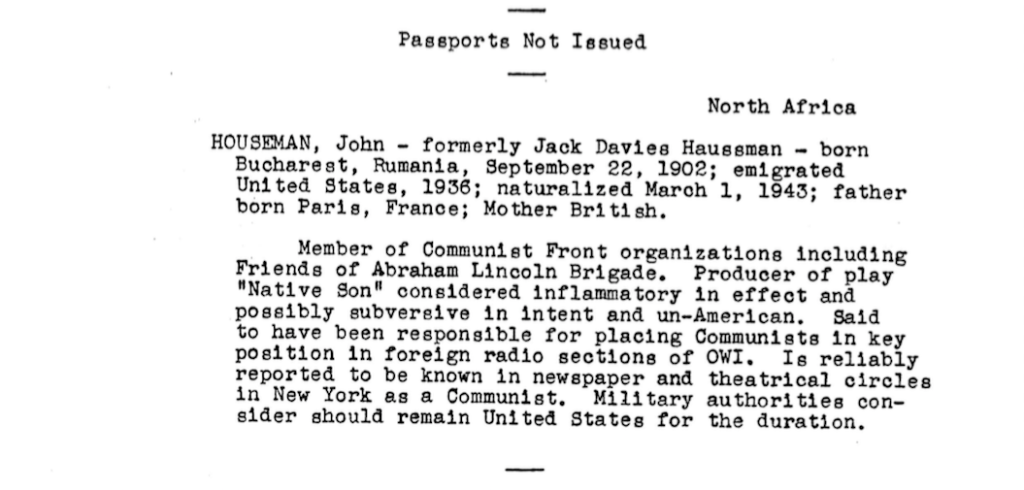

Addendum to April 5-6, 1943 memoranda from Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles to Honorable Marvin H. McIntyre, Secretary to the President, The White House.

“Passports Not Issued

North Africa

HOUSEMAN, John – formerly Jack Davies Haussman – born Bucharest, Rumania, September 22, 1902; emigrated United States, 1936; naturalized Maroh 1, 1943; father born Paris, France; Mother British.

Member of Communist Front organizations including Friends of Abraham Lincoln Brigade. Producer of play “Native Son” considered inflammatory in effect and possibly subversive in intent and un-American. Said to have been responsible for placing Communists in key position in foreign radio sections of OWI. Is reliably reported to be known in newspaper and theatrical circles in New York as a Communist. Military authorities consider should remain United States for the duration.”

John Houseman may not have been a registered Communist Party member, but there is evidence that both before and during his employment as VOA director he enthusiastically supported Soviet policies, sometimes against American interests, although he probably did not think he was in any way disloyal or wrong in his official actions. He appeared to have been a true believer in some of the lofty ideas of communism, as well as Stalin’s good intentions. And he was by far not alone in that belief among radically left-leaning West European and American intellectuals and artists of that period who were faced with the growth of fascism in Europe and persistent racism and discrimination in the United States.

It was true, as the State Department memo had warned, that Houseman was “responsible for placing Communists in key positions in foreign radio sections of OWI.” They were his ideological and intellectual companions. It turned out that in some cases, their loyalties were not with the United States, but with the Kremlin and the communist movement. After the war’s end, not many, but several of these VOA broadcasters, went back to their native countries to work for the Soviet-imposed regimes and engaged in anti-American propaganda. Several of them had worked during the war on the Voice of America Polish desk.

Such unmonitored VOA hiring practices, although not specifically about Houseman, were noted by one of OWI’s World War II era German-language editors, Austrian-Jewish refugee journalist Julius Epstein, who himself had been for a few months a member of the German Communist Party in his student years in Germany.

“When I, in 1942, entered the services of what was then the ‘Coordinator of Information’ which became after a few months the O.W.I., I was immediately struck by the fact that the German desk was almost completely seized by extreme left-wingers who indulged in a purely and exaggerated pro-Stalinist propaganda.” 19

The only far-fetched claim in the State Department memo supporting the accusations against John Houseman was that Native Son, a book by an African American writer Richard Wright, which Houseman co-produced as a play before he started working for the U.S. government, was somehow “possibly subversive in intent and un-American.” Wright’s book was definitely not subversive, but Houseman’s theatrical production of it was possibly deceptive in whitewashing the violent nature of communism, which Wright himself was not afraid to show in his book. Richard Wright broke with the Communist Party and published an anti-communist essay in the 1949 book, The God That Failed. After announcing his intention to leave the Communist Party, Communists called Richard Wright “a traitor.” Two white communists beat him up at a May Day march in Chicago in 1936

Another one of Houseman’s OWI patrons, Joseph Barnes, was listed in the addendum to the same State Department memo as having received a U.S. passport to accompany Republican politician Wendell Willkie on his trip abroad as Roosevelt’s informal envoy to show bipartisan American support for the war. The memo only raised questions about Barnes’ naïve pro-Soviet views and following “the Party line.” Barnes’ position within the organization was above Houseman’s. Houseman dedicated the first edition of his memoirs to Barnes.

Any journalist who had spent some time in Stalinist Russia, as Barnes had, and remained a believer in communism and Stalin, could not have possibly been effective as a producer of truthful and objective U.S. broadcasts, but the memo did not offer any recommendations about his continued employment. The State Department allowed him to travel abroad on official business.

A scholar of U.S. government wartime propaganda, Holly Cowan Shulman, described Barnes as “unquestionably and deeply loyal to the United States.” She wrote sympathetically about the leftist idealism of the early VOA leaders, but also quoted American diplomat and statesman George F. Kennan who knew Barnes while he was a foreign correspondent in the Soviet Union in the 1930s, describing him as “much more pro-Soviet than the rest of us–naively so… .” OWI director Elmer Davis confirmed after the war that he had fired Barnes for opposing polices of the Roosevelt administration but described him as a loyal American:

“I thought he was a very able man, but he was too much addicted to what we called in the war ‘localitis. He was head of the New York office, and it was eventually found desirable to remove him because he didn’t seem to be quite sufficiently in sympathy with the policies laid down in Washington. But I never had the slightest question about his loyalty.” 20

Addendum to April 6, 1943 memorandum from Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles to Honorable Marvin H. McIntyre, Secretary to the President, The White House.

OFFICE OF WAR INFORMATION

Passports Issued

Around the world with Wilkie

BARNES, Joseph Fels – born Montclair, New Jersey July 21, 1904; father born New York; Mother Australia.

News correspondent in USSR several years. Alleged to have stated that the Soviet Constitution is the best ever written. Supported the left wing of the American Newspaper Guild. It is reliably stated that there has been no crucial point in Russian development, since 1934, when Barnes has not followed the Party line and has not been much more successful than the official spokesman in giving it a form congenial to the American way of expression.

Former Office of War Information director Elmer Davis confirmed in a congressional testimony on November 11, 1952 another of Julius Epstein’s charges about hiring communists and communist sympathizers to work on VOA wartime broadcasts.

“One of the greatest OWI scandals broke when Frederick Woltman published his article entitled ‘A. F. of L. and CIO Charge OWI Radio as Communistic.’

Woltman’s article appears in the New York World-Telegram of October 4, 1943. It showed that the A. F. of L. as well as the CIO, the two great American labor organizations, which nobody but the Communists ever accused of being reactionary, withdrew their cooperation from the OWI’s labor desk because of the latter’s outspoken Communist attitude.” 21

Elmer Davis confirmed that he had removed the person in charge of the OWI labor desk. He also confirmed that he had “fired the head of the Greek desk in New York because he violated a directive sent from Washington about the handling of the news of Greece.”

All in all, Davis admitted to firing about a dozen employees because of their pro-communist views and associations, but also pointed out that in 99 percent of cases suspicions of employees being Communist Party members turned out to be unfounded. He did not tell members of Congress in 1952 whether John Houseman was among those he had fired for being communists. Houseman always insisted that he had resigned on his own, but acknowledged that he would have been fired if he had stayed longer at his job. Davis admitted to members of Congress that some communists were missed and remained on the OWI payroll through the war. 22

The addressee of Welles’ memo about Houseman and Office of War Information employees was Marvin H. McIntyre, Secretary to the President and Roosevelt’s close friend and political advisor. At one time in his professional career as a journalist, McIntyre was the city editor at the Washington Post.

While the State Department expressed its concerns quietly to the White House, members of the U.S. Congress from both parties, though mostly Republicans, were speaking out in public, warning about communists working on Voice of America broadcasts. At that time, even they did not fully realize how easy it was for foreign, partisan, or personal influence to compromise U.S. interests in a government organization operating as a semi-journalistic outlet without effective security or institutional controls and oversight. Deeply suspicious of the Office of War Information, the lawmakers in Congress eventually cut most of OWI’s domestic propaganda budget even while the war was still going on and from time to time seriously threatened to defund Voice of America overseas operations as well, with each new management or programming scandal made public. VOA’s budget was somewhat reduced in 1943, but overseas broadcasting was not eliminated.

Members of Congress continued to express concerns about the OWI and VOA throughout the war. Republicans and Democrats often focused on VOA broadcasts to Poland, which was the largest country threatened to be dominated by the Soviet Union and was the first victim of Nazi and Soviet aggression in World War II.

While some members of the Roosevelt administration had chosen to ignore the earlier Nazi-Soviet alliance, many members of Congress along with many ordinary anti-communist Americans did not. Two weeks after the State Department memo reached the FDR White House, Congressman Roy O. Woodruff (R-MA) delivered on April 20, 1943 on the floor of the House of Representatives another early warning of Soviet influence over the Office of War Information and its Voice of America shortwave, medium wave and long wave radio outreach abroad. In addition to VOA broadcasts to Poland, Congressmen Woodruff also focused on VOA broadcasts to Yugoslavia, charging that both might have fallen under communist influence.

“…reports are constantly reaching me and other Members of Congress that the propaganda activities of the Polish Unit of O. W. I.’s Overseas Division are destroying rather than building the morale of the helpless Polish people.

These reports tell us that much of this propaganda follows the American Communist Party line and is designed to prepare the minds of the Polish people to accept partition, obliteration, or suppression of their nation when the fighting ends. The same is true of Yugoslavia, where, I am told, the name of the great Mihailovitch [Draža Mihailović, a Yugoslav Serb general during World War II executed by the Communists after the war] is blocked out by O. W. I. radicals.

If it is true that Communists have infiltrated into the O.W.I.’s Overseas Division and are following the party line in their propaganda to Poland, as well as other countries, then it is an outrageous violation of the faith that is reposed in Elmer Davis and Robert Sherwood. If this is not true, then the Polish people in America are entitled to have allayed the rumors which may be enemy inspired.” 23

A little over a year later, a Democratic politician, Congressman John Lesinski Sr. (D-MI), told the House of Representatives about Soviet propaganda in VOA radio broadcasts to Yugoslavia. His remarks appeared in the Congressional Record on June 23, 1944 Members of Congress were also concerned about pro-communist VOA broadcasts in Greek, French, and Italian, as well as some VOA broadcasts in English.

“Under present war restrictions, news in regard to our allies—or, for that matter, any foreign country—is not printed unless it has the approval of the Office of War Information, of which Hon. Elmer Davis is Director.

I have followed with a great deal of interest the releases in regard to Yugoslavia, and I cannot understand why the Director of War Information is feeding Communist propaganda to the American people in regard to the conditions in Yugoslavia.” 24

OWI director Elmer Davis told a bipartisan investigative committee of the U.S. House of Representatives in 1952 that Congressman Lesinski was lying. Lesinski was not lying, but by then he was no longer alive to respond to Davis’ attack.

“I recall that he [Congressman John Lesinski Sr.] made a speech in the summer of 1943 which contained more lies than were ever comprised in any other speech made about the Office of War Information, and that is saying quite a lot. I may say that I have made that statement to Mr. Lesinski before he died. I mean that I have not waited until after he is dead. I told him so in writing when he repeated some of those statements 2 or 3 years ago. I asked him where he got the information, because that was a perfectly absurd speech to be made by a Member of the Congress of the United States who knows anything about American politics or the American news business.” 25

[Time magazine cover with OWI director Elmer Davis, March 15 1943.]

What Congressman Lesinski had said about OWI in 1943 has been confirmed by multiple sources. The arrogance of Elmer Davis, the journalist who accepted at face value the greatest Soviet propaganda lie and repeated it to domestic and foreign audiences despite warnings and evidence of Soviet guilt, was boundless and typical of the agency’s top brass of that period.

A response by Davis in November 1952 to the members of the bipartisan congressional select committee was also illustrative of his lack of journalistic curiosity and political imagination, as the Katyn story, if correctly and accurately reported to American and foreign audiences by the U.S. government media, such as the Voice of America, could have had an early impact on the future course of U.S. relations with Soviet Russia and might have prevented some of the unfortunate concessions made to Stalin by President Roosevelt on behalf of the United States at Tehran and Yalta. Thanks to men like Davis and Houseman, the truth unfavorable to Russia was suppressed. By all indications, they seemed to have known what they were doing, even though they denied it. Houseman did not deny it because his complicity in the Katyn cover-up was never exposed.

“Mr. Davis. I don’t remember. I may say, Mr. Counsel, that this was not one of the major issues that I had to deal with at that time, from my point of view. To a Pole it was certainly the most important issue in the world, but to me, as to the head of every department or agency of Government, about that time of year the principal question was how his budget was going to get through Congress, and that absorbed most of my time. So whether I asked advice on this question from either Mr. Hull or Mr. Welles, I don’t remember. I don’t recall seeing this memorandum from Mr. Berle, although it is conceivable that I might have. I don’t know.” 26

A strikingly different picture of Elmer Davis as a respected American newsman emerges from laudatory descriptions found online. Some of them even excuse his role in OWI’s production of propaganda films in support of the internment of Japanese Americans by claiming that he had opposed their production—a strange attempt at whitewashing since he was in charge of the government agency which produced them. The same attempts at whitewashing appear in books, articles, and in most online mentions of John Houseman.

“Elmer Holmes Davis (1890-1958) was a respected newspaper journalist, novelist, essayist, and radio announcer. His insightful and candid commentary on Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) Radio provided the people of the United States with a trusted voice of reason and authority during the tumultuous years of World War II. Later, during the 1950s, Davis helped rally popular opinion against the Communist conspiracy theories of Senator Joseph McCarthy.” 27

Davis became one of many critics who justly condemned Senator McCarthy. But, except in his congressional testimony in 1952 given under oath, Davis never pointed out later that he himself had fired a few people at the Office of War Information suspected of being communists, although he did not fire all communists and certainly not all active supporters of communism and Stalin’s agenda.

Complaints about VOA broadcasts expressed by representatives of ethnic communities to their members of Congress also played a role in getting U.S. lawmakers involved in efforts to correct the perceived pro-Soviet propaganda, but with men like Davis, Sherwood, Barnes and Houseman in charge, congressional interventions, though many, had a minimal effect on the propaganda policies of the Roosevelt administration targeting foreign audiences during the war.

The appeasement of Stalin and the domestic and foreign U.S. government propaganda support for it continued. Roosevelt correctly assumed that with some domestic propaganda, which the OWI helped to produce, including Elmer Davis’ broadcasts on domestic U.S. radio networks, the majority of ethnic voters, including the Polish Americans, would still vote for him and for the Democratic Party, at least for the duration of the war. After the betrayal at Yalta became obvious, some of these American ethnic voters eventually switched to the Republican Party, especially when Ronald Reagan was running for president.

The wartime rumors of Soviet influence over the Voice of America overseas broadcasts were not inspired by Nazi Germany or Japan. They originated in the U.S. and were true. VOA wartime broadcasts were not only pro-Stalin. They were also critical of those whom communists saw as enemies of the Soviet Union: non-communist Poles, Yugoslavs, Greeks, Frenchmen, Italians and others organizing resistance against the Nazis in their countries or fighting alongside American and British troops, as the Polish Army under General Anders composed of former Stalin’s prisoners in the Soviet Gulag did in North Africa, Italy and in other parts of Western Europe. Their only crime was their lack of unquestioned support for Soviet Russia and Stalin.

The democratic governments in exile complained to the Office of War Information and to the State Department about VOA communist propaganda undermining their anti-Nazi resistance efforts, but their complaints, while received with sympathy by American diplomats, did not have any major lasting effect on VOA broadcasts.

Stanisław Mikołajczyk, Prime Minister of Poland’s government in exile based in London who during the war met with President Roosevelt in Washington, recalled later that Polish diplomats raised the issue of Soviet propaganda in Voice of America broadcasts with State Department officials. Diplomats from other countries did as well. They were not protesting against VOA reporting news but against what many Americans who paid attention, including members of Congress, saw as blatant pro-Soviet VOA propaganda.

“We finally protested to the United States State Department about the tone of OWI broadcasts to Poland. Such broadcasts, which we carefully monitored in London, might well have emanated from Moscow itself. The Polish underground wanted to hear what was going on in the United States, to whom it turned responsive ears and hopeful eyes. It was not interested in hearing pro-Soviet propaganda from the United States, since that duplicated the broadcasts sent from Moscow.” 28

The 1943 memo to the FDR White House from Under Secretary Sumner Welles may have been partly in response to some of these complaints. The memo may have also contributed to the departure of John Houseman, Joseph Barnes and several other higher-level OWI officials and a few communist broadcasters in the summer of 1943, but their leaving did not have a long-lasting impact on VOA programs.

Pro-Soviet and pro-communist propaganda continued, as did VOA’s hostility toward governments in exile, which were America’s allies but were considered enemies by Stalin. Soviet propaganda labeled them as reactionary, fascist, anti-Russian, anti-Semitic and pro-Nazi—similar to some of the labels used by Russian propaganda and others today.

Houseman’s and Barnes’ forced departure from OWI did not lead to the removal of VOA broadcasters they had hired. According to Julius Epstein, who later wrote a groundbreaking book Operation Keelhaul exposing mass deportations of Russian and other anti-communist refugees from Western Europe to the Gulag under secret Western agreements with Stalin, some of the early pro-Soviet VOA broadcasters were still employed by the organization in 1950.

By then, however, VOA also had a group of anti-communist East European refugee journalists who were hired after the war. In the early 1950s, they were complaining of not being allowed by the VOA management in the State Department and in some cases by their own service directors and managers directly above them to report fully on Soviet human rights abuses.

“There are still too many of the old OWI [Office of War Information] employees working for the Voice, both in this country and overseas. I mean those writers, translators and broadcasters who so wholeheartedly and enthusiastically tried for many years to create ‘love for Stalin,’ when this was the official policy of our ill-advised wartime Government and of our military government in Germany. There is no doubt that all those employees were at that time deeply convinced of the absolute correctness of that pro-Stalinist propaganda. How can we expect them to do the exact opposite now?” 29

Epstein made an accurate observation that those in charge of VOA broadcasts, probably even those who later joined communist regimes in Eastern Europe, did not think there was anything wrong about their pro-Stalinist and pro-communist propaganda. They associated the Soviet Union, Stalin and communism with anti-fascism, social justice, and progress.

Even without the secret State Department memo, there has been already much evidence in the public record for many years showing that in a major collusion with a foreign power ultimately hostile to the United States, Western democracy, and liberal values—officials in charge of wartime overseas broadcasts in the Office of War Information coordinated their propaganda with Soviet Union, spread Soviet disinformation, and censored any news unfavorable to the Soviet Union or to its dictatorial communist leader Joseph Stalin. They did it largely on their own, without any known U.S. government directives from outside the organization.

While President Roosevelt’s support for Stalin and Soviet Russia during the war and his willingness to betray or abandon America’s smaller allies against Nazi Germany have been well documented, even he eventually lost patience with his own pro-Soviet propagandists at the Voice of America.

None of this VOA history, however, has been widely known or analyzed. This allows the same mistakes and failures of public oversight to be repeated with a predictable regularity. Those few who did know about VOA’s less than glorious early history were associated in some way with the organization or U.S. public diplomacy. They had more reasons to suppress such information than to make it public. The Welles’ memo remained undiscovered for decades after its declassification.

The evidence of major Soviet influence within the Voice of America during World War II and VOA’s continued reluctance to fully expose true history of communist human rights abuses in its broadcasts for several years after the war—be it from partisan convictions in an effort to protect the legacy of the Roosevelt administration, ideological convictions to avoid demonizing Soviet Russia, or misplaced fears that telling the whole truth about Stalin’s crimes would immediately cause bloody though fruitless uprisings in Eastern Europe—was temporarily brought to broader public attention mostly by members of Congress in the early 1950s as a result of the Korean War.

A little later, in 1965, former President Eisenhower also briefly alluded in his post-White House years memoirs to VOA’s wartime record of journalistic collusion with Russia. As a military leader during World War II, he must have been still upset to have mentioned it years later during the Cold War with the Soviet Union when VOA was already playing a useful although still less than fully effective role in countering Soviet propaganda. General Eisenhower had been actively engaged in earlier efforts to create Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty as more effective media outlets against the Soviet Union. His critical comment appeared in a footnote to a paragraph in which he expressed his own concerns with what he saw as Voice of America’s unethical journalism in support of partisan political advocacy in at least one foreign policy incident during his own administration.

“During World War II the Office of War Information had, on two occasions in foreign broadcasts, opposed actions of President Roosevelt; it ridiculed the temporary arrangement with Admiral Darlan in North Africa and that with Marshal Badoglio in Italy. President Roosevelt took prompt action to stop such insubordination.” 30

President Eisenhower was right. In both cases during World War II, and to a much lesser extent even briefly during his administration, some VOA officials, editors and reporters sought to create and influence news and U.S. policy through their own ideological commentary rather than merely reporting news. During World War II, General Eisenhower and the Army Intelligence had legitimate concerns that some VOA broadcasters following closely the communist and pro-Soviet line could endanger the lives of American soldiers.

An OWI document with names of top officials in charge of VOA broadcasts. They are not listed in a hierarchical order and are not their actual signatures.

The Voice of America has had an unhappy history of both promoting Soviet propaganda and at times censoring those who tried to expose it, including for several years in the 1970s Russian Nobel Prize writer Alexandr Solzhenitsyn. Much of the censorship first originated in Moscow and was adopted by VOA during World War II. In the spring of 1943, John Houseman and his bosses—Robert E. Sherwood, Joseph Barnes and OWI director Elmer Davis—accepted at face value and repeated one of the greatest Soviet propaganda lies of the 20th century. The Voice of America under their direction became an active participant for several years in what was perhaps the most outrageous Soviet fake news story of World War II and the post-war period.

Despite abundant evidence to the contrary, the OWI initiated overseas VOA broadcasts as well as domestic broadcasts in the United States in support of the blatantly false Soviet propaganda claim that Russia and Joseph Stalin had nothing to do with the brutal mass murder of more than 20 thousand Polish military officers and intellectual leaders held in Soviet captivity since 1939 following the joint German and Soviet partition of Poland.

VOA continued to spread Soviet disinformation and suppressed the truth about the Soviet Katyn Forest massacre, despite having been told by the State Department in mid-April 1943 that taking sides on the guilt for the slaughter of Polish prisoners of war in Russia would not be advisable. The Voice of America under Houseman, Barnes, Sherwood and Davis opted instead for repeating and amplifying the Soviet propaganda lie on Katyn, which later they claimed did not seem to them to be a lie.

Robert Sherwood advised VOA broadcasters in his “Weekly Propaganda Directive” dated May 1, 1943 that “some Poles” who did not accept the Soviet explanation, may be cooperating with Hitler in causing division among the allies, even though Poland was a Nazi-occupied country where such cooperation with Nazi Germany on the part of the underground state, its underground army or the government in exile in London was beyond unthinkable.

“Some Poles are consciously or unconsciously cooperating with Hitler in his campaign to spiritually divide the United Nations.” 31

On the Katyn massacre issue, however, the Roosevelt White House did not intervene. President Roosevelt was secretly pleased with such misleading VOA reporting because it protected the U.S.-Soviet war alliance. Roosevelt and the War Department kept secret U.S. and British intelligence information showing Soviet guilt.

It was only when VOA journalists tried to undermine FDR’s own wartime strategy and risked the lives of American soldiers that the White House finally put its foot down. Several OWI officials lost their jobs in the summer of 1943, but even that move by the FDR administration did not have much effect on the largely autonomous and unmonitored federal agency for the next several years.

Contrary to suggestions of officials in Washington trying to suppress legitimate news reporting by wartime Voice of America broadcasters then based in New York, there is no evidence in OWI or State Department files that the State Department or the War Department were actively trying to control the content of VOA broadcasts or even paid much attention to them. The Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursors of the CIA, did pay attention to some extent, but most disagreements were resolved and a division of propaganda efforts was agreed upon by the two agencies. The State Department and the War Department generally did nothing to intervene until scandals triggered by VOA’s ideological commentaries forced them to act. These were not cases of U.S. military authorities or U.S. diplomats trying to impose or practice prior censorship of overseas radio broadcasts in a heavy-handed way, but rather rare and weakly phrased attempts to prevent the Voice of America from reporting false news and advocating policies too favorable to the Soviet Union and the communist movement when higher-level officials in the Roosevelt administration outside the OWI became aware that they could harm the United States and its fighting forces. There was censorship of purely military information that could prove useful to the enemy.

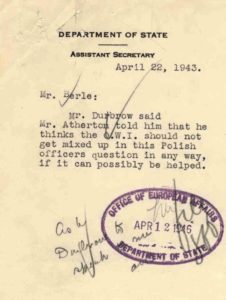

A previously classified note from the State Department, dated April 22, 1943, was a typical low-key recommendation written in a diplomatic language which suggested that senior U.S. diplomats most likely told OWI and VOA officials to refrain from accepting and promoting the Soviet explanation for the Katyn massacre. Pro-Soviet OWI executives and VOA managers and broadcasters simply ignored such warnings, which also came from other sources.

“Mr. Berle:

Mr. [Elbridge] Dubrow said Mr. [Ray] Atherton told him that he thinks the O.W. I. should not get mixed up in this Polish officers question in any way, if it can possibly be helped.”

Elbridge Dubrow and Ray Atherton were high-level State Department officials responsible for European affairs. Adolf Berle was the Assistant Secretary of State.

The State Department was by then aware that the OWI Director, American radio journalist Elmer Davis, and the Voice of America leadership, were already fully engaged in blaming the Katyn massacre on Nazi Germany in domestic radio broadcasts in the United States as well as in overseas VOA broadcasts. If anything, State Department diplomats were trying to tell VOA journalists to practice some journalistic caution, but the pro-Soviet ideologues would not heed their advice.

American and foreign audiences were being deceived by both American and Soviet propaganda. As for VOA, it was propaganda in the name of the U.S. government paid for American taxpayers but failing to reflect accurately in some cases even the FDR administration’s policies and certainly failing to present all American viewpoints. Elmer Davis’ anti-Nazi commentaries, which included a heavy dose of Soviet propaganda and denials of Stalin’s crimes and his imperialistic intentions, were broadcast by the Voice of America to audiences abroad, as well as on domestic radio networks in the United States. 32

The earlier April 6, 1943 secret memo from Under Secretary Sumner Welles, believed to be one of the earliest official warnings of communist influence within the Voice of America, was written several days before the OWI ignored the State Department’s cautionary note on the Katyn incident. Houseman wrote after the war that he had tried to get the State Department’s decision about his U.S. passport reversed by asking Robert Sherwood to make an appeal to FDR’s strongly pro-Soviet advisor Harry Hopkins. If such an appeal was made, it did not succeed.

Houseman was convinced that it was Assistant Secretary of State Adolf A. Berle who had ruled against him (he gave his title as “Undersecretary of State”). He also blamed the Polish government in exile, Polish Americans and a State Department official in charge of issuing passports who was partly Polish American. He probably did not know that the decision not to send him abroad as a U.S. government representative had been discussed in some detail between the State Department and the White House.

The secret allegations against one of the key persons in charge of U.S. overseas radio broadcasts were, in fact, sent to the Roosevelt White House by Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, a liberal Democrat. The memo said that it was written in response to an inquiry from the President’s Secretary. Sumner Welles was a Roosevelt loyalist, a close friend of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his family, and a distinguished diplomat who held the second-highest position in the State Department. At one point he served as the Acting Secretary of State. He also accompanied President Roosevelt on one of his trips abroad. There were reports that FDR preferred Welles to Secretary of State Cordell Hull and only reluctantly accepted his resignation later in 1943 when Welles’ rivals disclosed to the media his homosexual indiscretions, some of which were true, although he denied the incident which led to his resignation.

The secret allegations against one of the key persons in charge of U.S. overseas radio broadcasts were, in fact, sent to the Roosevelt White House by Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, a liberal Democrat. The memo said that it was written in response to an inquiry from the President’s Secretary. Sumner Welles was a Roosevelt loyalist, a close friend of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his family, and a distinguished diplomat who held the second-highest position in the State Department. At one point he served as the Acting Secretary of State. He also accompanied President Roosevelt on one of his trips abroad. There were reports that FDR preferred Welles to Secretary of State Cordell Hull and only reluctantly accepted his resignation later in 1943 when Welles’ rivals disclosed to the media his homosexual indiscretions, some of which were true, although he denied the incident which led to his resignation.

Despite the sexual scandal, Roosevelt and Welles remained in close contact. FDR tried later to revive his career and send him on a diplomatic mission to Moscow as his representative, but Welles declined the offer, fearing that it might undermine the position of Secretary Hull, even though the two men did get along well when Welles was still with the State Department.

Houseman did not have anywhere near the same professional or social standing as Welles or another one of his critics in the State Department, Assistant Secretary of State Adolf A. Berle, who like Welles was also a close friend and advisor to President Roosevelt. There is no evidence that President Roosevelt had ever met the first VOA director. Houseman was, however, a protégé of some of FDR’s and Eleanor Roosevelt’s other associates, Robert E. Sherwood and Joseph Barnes, who themselves were strongly pro-Soviet, much more so than even the president and his wife.

There is no evidence in the archival records that any of the top OWI officials were actual Soviet-paid agents of influence. The State Department memo did not allege such a connection. They were rather ideological allies who felt the need to promote a good relationship with Stalin’s Russia and promote its interests, just as today’s corporate businessmen put in charge of U.S. international broadcasting might want to keep a good relationship with Putin’s Russia or with China. Similarly, these highly partisan government executives may want to promote domestic partisan causes, but during World War II, VOA officials and broadcasters favored the policy line from Moscow and its communist movements abroad for ideological rather than partisan, personal or business reasons.

Houseman’s links with the Communist Party prior to his employment with the U.S. government were never fully investigated at the time or afterwards. He somehow escaped Senator McCarthy’s scrutiny, who instead focused on his boss, Joseph Barnes. In all likelihood, McCarthy did not know of the 1943 State Department memo which listed both Barnes and Houseman as possible communist and Soviet sympathizers, with Barnes being nevertheless given a U.S. passport for his official travel while Houseman’s request was repeatedly denied. Barnes vigorously challenged McCarthy’s accusations that he had been a Communist Party member.

In later years, Houseman did not try to hide his collaboration with communist activists, with whom he had worked in his theatrical career in the 1930s, but such information was omitted from books and articles about VOA written by others. In his book, he admitted to receiving political instructions from Communist Party members, but never said he was a dues-paying communist. His memoirs, Unfinished Business, include more than a dozen references to his contacts with the U.S. Communist Party.

Unlike other progressive Americans who eventually became disillusioned with Stalinism, Houseman never strongly condemned Stalin. In discussing the State Department’s refusal to provide him with a U.S. passport for government travel abroad, he lashed out in his book at his perceived enemies and critics with ethnic stereotypes and unlikely conspiracy theories.

“To explain this refusal various theories were put forward: one was that Mrs. Shipley, head of the Passport Division, being herself of Polish origin, was taking revenge for the injuries supposedly inflicted on the Polish government-in-exile by the Voice of America. Then, from some mysterious quarter, came the information that I had apparently been confused with Hans Haussmann–a notorious radical, formerly head of the Communist Party in Switzerland.” 33

The State Department memo, however, correctly presented Houseman’s identity and did not directly accuse him of being a Communist Party member in Switzerland or in the United States. Houseman may not have known that Ruth Bielaski Shipley, who was in charge of the passport Office in the State Department, was an American woman of mixed religious background who appears not to have emphasized her ethnic roots in any accessible public comments. One of her uncles was a Polish officer, a friend of President Lincoln, who had volunteered for the Union Army and was killed in the Civil War. She was the daughter of a Methodist minister Alexander Bielaski and his wife, Roselle Israel Bielaski, and the first woman to become the head of the Passport Division in the Department of State. 34 Ruth Shipley was indeed notorious during the Cold War for denying U.S. passports for private travel abroad to many U.S. born and naturalized American citizens suspected of being members of the Communist Party on the basis that they presented a risk to U.S. security. Her brother, Alexander Bruce Bielaski, was from 1912 to 1919 the director of the Bureau of Investigation (which was renamed in 1935 to the Federal Bureau of Investigation – FBI). While being in charge of the Passport Division, Shipley was often criticized for her zeal and her lack of transparency—foreign travel was not yet seen as a constitutional right or accorded due process in passport cases—but in Houseman’s case, it was not a private application but a passport request for official U.S. government travel. She was well-regarded at the time by Secretaries of State of Democratic and Republican administrations.

If the Army Intelligence recommended that he not travel abroad as a U.S. government employee, Shipley who was known for her strict observance of rules and regulations would not have thought twice about denying him an official passport if she had been asked to make a decision in his case. She could have been overruled by higher-level State Department officials or the White House if anyone wanted to intervene. If it had been her decision to deny Houseman a diplomatic passport, it was not changed but rather confirmed by officials just below the Secretary of State.

Shipley seemed to have been following not just what were then strict U.S. government rules but also the Roosevelt administration foreign policy. In 1944, she was criticized for issuing a passport to an obscure Polish-American Catholic priest, Father Stanislaus Orlemanski, who went to see Joseph Stalin on a pro-Soviet propaganda trip arranged by the Soviet government. Such a trip had to have had the administration’s initial backing, but in the end turned out to be controversial. A New York Times article stated that President Roosevelt had to defended Shipley’s decision at a press conference on May 9, 1944 by pointing out that Father Orlemanski’s mission to Moscow was a private trip, and reportedly said, “When anyone has got by Mrs. Shipley,… one can be sure the law has been lived up to.” 35 This controversy erupted already after Houseman’s departure from the OWI.

Robert Sherwood and his colleagues wanted badly to exploit the priest’s trip for propaganda purposes to show that there is freedom of religion in Soviet Russia and that the fear of Russia and communism are misplaced. 36

To their great disappointment, the Office of War Information in Washington advised Sherwood, then based in London to coordinate American and Soviet propaganda, that too much U.S. government’s publicity for Father Orlemanski’s trip to Russia would not be advisable.